Bryan Helmkamp

Applying the Unix Philosophy to Object-Oriented Design

Today I’m thrilled to present a guest post from my friend John Pignata. John is Director of Engineering Operations at GroupMe.

In 1964, Doug McIlroy, an engineer at Bell Labs, wrote an internal memo describing some of his ideas for the Multics operating system. The surviving tenth page summarizes the four items he felt were most important. The first item on the list reads:

“We should have some ways of coupling programs like [a] garden hose – screw in another segment when it becomes necessary to massage data in another way.”

This sentence describes what ultimately became the Unix pipeline: the chaining together of a set of programs such that the output of one is fed into the next as input. Every time we run a command like tail -5000 access.log | awk '{print $4}' | sort | uniq -c we’re benefiting from the legacy of McIlroy’s garden hose analogy. The pipeline enables each program to expose a small set of features and, through the interface of the standard streams, collaborate with other programs to deliver a larger unit of functionality.

It’s mind-expanding when a Unix user figures out how to snap together their system’s various small command-line programs to accomplish tasks. The pipeline renders each command-line tool more powerful as a stage in a larger operation than it could have been as a stand-alone utility. We can couple together any number of these small programs as necessary and build new tools which add specific features as we need them. We can now speak Unix in compound sentences.

Without the interface of the standard streams to allow programs to collaborate, Unix systems might have ended up with larger programs with duplicative feature sets. In Microsoft Windows, most programs tend to be their own closed universes of functionality. To get word count of a document you’re writing on a Unix system, you’d run wc -w document.md. On a system running Windows you’d likely have to boot the entire Microsoft Word application in order to get a word count of document.docx. The count functionality of Word is locked in the context of use of editing a Word document.

Just as Unix and Windows are composed of programs as units of functionality, our systems are composed of objects. When we build chunky, monolithic objects that wrap huge swaths of procedural code, we’re building our own closed universes of functionality. We’re trapping the features we’ve built within a given context of use. Our objects are obfuscating important domain concepts by hiding them as implementation details.

In coarse-grained systems, each single object fills multiple roles increasing their complexity and resistance to change. Extending an object’s functionality or swapping out an implementation for another sometimes involves major shotgun surgery. The battle against complexity is fought within the definition of every object in your system. Fine-grained systems are composed of objects that are easier to understand, to modify, and to use.

Some years after that memo, McIlroy summarized the Unix philosophy as: “write programs that do one thing and do it well. Write programs to work together.” Eric Raymond rephrased this in The Art of Unix Programming as the Rule of Modularity: “write simple parts connected by clean interfaces.” This philosophy is a powerful strategy to help us manage complexity within our systems. Like Unix, our systems should consist of many small components each of which are focused on a specific task and work with each other via their interfaces to accomplish a larger task.

Everything But the Kitchen Sink

Let’s look at an example of an object that contains several different features. The requirement represented in this code is to create an old-school web guestbook for our home page. For anyone who missed the late nineties, like its physical analog a web guestbook was a place for visitors to acknowledge a visit to a web page and to leave public comments for the maintainer.

When we start the project the requirements are straightforward: save a name, an IP address, and a comment from any visitor that fills out the form and display those contents in an index view. We scaffold up a controller, generate a migration, a new model, sprinkle web design in some ERB templates, high five, and call it a day. This is a Rails system, I know this.

Over time our requirements begin growing and we slowly start adding new features. First, in real-life operations we realize that spammers are posting to the form so we want to build a simple spam filter to reject posts containing certain words. We also realize we want some kind of rate-limiting to prevent visitors from posting more than one message per day. Finally, we want to post to Twitter when a visitor signs our guestbook because if we’re going to be anachronistic with our code example, let’s get really weird with it.

require "set"

class GuestbookEntry < ActiveRecord::Base

SPAM_TRIGGER_KEYWORDS = %w(viagra acne adult loans xxx mortgage).to_set

RATE_LIMIT_KEY = "guestbook"

RATE_LIMIT_TTL = 1.day

validate :ensure_content_not_spam, on: :create

validate :ensure_ip_address_not_rate_limited, on: :create

after_create :post_to_twitter

after_create :record_ip_address

private

def ensure_content_not_spam

flagged_words = SPAM_TRIGGER_KEYWORDS & Set.new(content.split)

unless flagged_words.empty?

errors[:content] << "Your post has been rejected."

end

end

def ensure_ip_address_not_rate_limited

if $redis.exists(RATE_LIMIT_KEY)

errors[:base] << "Sorry, please try again later."

end

end

def post_to_twitter

client = Twitter::Client.new(Configuration.twitter_options)

client.update("We had a visitor! #{name} said #{content.first(50)}")

end

def record_ip_address

$redis.setex("#{RATE_LIMIT_KEY}:#{ip_address}", RATE_LIMIT_TTL, "1")

end

end

class GuestbookEntry < ActiveRecord::Base

SPAM_TRIGGER_KEYWORDS = %w(viagra acne adult loans xxx mortgage).to_set

RATE_LIMIT_KEY = "guestbook"

RATE_LIMIT_TTL = 1.day

validate :ensure_content_not_spam, on: :create

validate :ensure_ip_address_not_rate_limited, on: :create

after_create :post_to_twitter

after_create :record_ip_address

private

def ensure_content_not_spam

flagged_words = SPAM_TRIGGER_KEYWORDS & Set.new(content.split)

unless flagged_words.empty?

errors[:content] << "Your post has been rejected."

end

end

def ensure_ip_address_not_rate_limited

if $redis.exists(RATE_LIMIT_KEY)

errors[:base] << "Sorry, please try again later."

end

end

def post_to_twitter

client = Twitter::Client.new(Configuration.twitter_options)

client.update("We had a visitor! #{name} said #{content.first(50)}")

end

def record_ip_address

$redis.setex("#{RATE_LIMIT_KEY}:#{ip_address}", RATE_LIMIT_TTL, "1")

end

end

These features are oversimplified but set that aside for the purposes of this example. The above code shows us a hodgepodge of entwined features. Like the Microsoft Word example of the word count feature, the features we’ve built are locked within the context of creating a GuestbookEntry.

This kind of approach has several real-world implications. For one, the tests for this object likely exercise some of these features in the context of saving a database object. We don’t need to roundtrip to our database in order to validate that our rate limiting code is working, but since we’ve hung it off an after_create callback that’s likely what we might do because that’s the interface our application is using. These tests also likely littered with unrelated details and setup due to the coupling to unrelated but neighboring behavior and data.

At a glance it’s difficult to untangle which code relates to what feature. When looking at the code we have to think about at each line to discern which of the object’s behavior that line is principally concerned with. Clear naming helps us in this example but in a system where each behavior was represented by a domain object, we’d be able to assume that a line of code related to the object’s assigned responsibility.

Lastly, it’s easy for us to glance over the fact that we have, for example, the acorn of a user content spam filter in our system because it’s a minor detail of another object. If this were its own domain concept it would be much clearer that it was a first-class role within the system.

Applying the Unix Philosophy

Let’s look at this implementation through the lens of the Rule of Modularity. The above code fails the “simple parts, clean interfaces” sniff test. In our current factoring, we can’t extend or change these features without diffusing more details about them into the GuestbookEntry object. The interface by which our model uses this behavior through internal callbacks trigged through the object’s lifecycle. There are no external interfaces to these features despite the fact that each has their own behavior and data. This object now has several reasons to change.

Let’s refactor these features by extracting this behavior to independent objects to see how these shake out as stand-alone domain concepts. First we’ll extract the code in our spam check implementation into its own object.

require "set"

class UserContentSpamChecker

TRIGGER_KEYWORDS = %w(viagra acne adult loans xrated).to_set

def initialize(content)

@content = content

end

def spam?

flagged_words.present?

end

private

def flagged_words

TRIGGER_KEYWORDS & @content.split

end

end

class UserContentSpamChecker

TRIGGER_KEYWORDS = %w(viagra acne adult loans xrated).to_set

def initialize(content)

@content = content

end

def spam?

flagged_words.present?

end

private

def flagged_words

TRIGGER_KEYWORDS & @content.split

end

end

Features like this have serious sprawl potential. When we first see the problem of abuse we’re likely we respond with the simplest thing that could work. There’s usually quite a bit of churn in this code as our combatants expose new weaknesses in our implementation. The rate of change of our spam protection strategy is inherently different than that of our GuestbookEntry persistence object. Identifying our UserContentSpamChecker as its own dedicated domain concept and establishing it as such will allow us to more easily maintain and extend this functionality independently of where it’s being used.

Next we’ll extract our rate limiting code. Some small changes are required to decouple it fully from the guestbook such as the addition of a namespace.

class UserContentRateLimiter

DEFAULT_TTL = 1.day

def initialize(ip_address, namespace, options = {})

@ip_address = ip_address

@namespace = namespace

@ttl = options.fetch(:ttl, DEFAULT_TTL)

@redis = options.fetch(:redis, $redis)

end

def exceeded?

@redis.exists?(key)

end

def record

@redis.setex(key, @ttl, "1")

end

private

def key

"rate_limiter:#{@namespace}:#{@ip_address}"

end

end

DEFAULT_TTL = 1.day

def initialize(ip_address, namespace, options = {})

@ip_address = ip_address

@namespace = namespace

@ttl = options.fetch(:ttl, DEFAULT_TTL)

@redis = options.fetch(:redis, $redis)

end

def exceeded?

@redis.exists?(key)

end

def record

@redis.setex(key, @ttl, "1")

end

private

def key

"rate_limiter:#{@namespace}:#{@ip_address}"

end

end

Now that we have a stand-alone domain object, more advanced requirements for this rate limiting logic will only change this one object. Our tests can exercise this feature in isolation apart from any potential consumer of its functionality. This will not only speed up tests, but help future readers of the code in reading the tests to understand the feature more quickly.

Finally we’ll extract our call to the Twitter gem. It’s tiny, but there’s good reason to keep it separate from our GuestbookEntry. Since Twitter and the gem are third-party APIs, we’d like to isolate the coupling to an adapter object that we use to hide the nitty-gritty details of sending a tweet.

class Tweeter

def post(content)

client.update(content)

end

private

def client

@client ||= Twitter::Client.new(Configuration.twitter_options)

end

end

def post(content)

client.update(content)

end

private

def client

@client ||= Twitter::Client.new(Configuration.twitter_options)

end

end

Now that we have these smaller components, we can change our GuestbookEntryobject to make use of them. We’ll replace the extracted logic with calls to the objects we’ve just created.

class GuestbookEntry < ActiveRecord::Base

validate :ensure_content_not_spam, on: :create

validate :ensure_ip_address_not_rate_limited, on: :create

after_create :post_to_twitter

after_create :record_ip_address

private

def ensure_content_not_spam

if UserContentSpamChecker.new(content).spam?

errors[:content] << "Post rejected."

end

end

def ensure_ip_address_not_rate_limited

if rate_limiter.exceeded?

errors[:base] << "Please try again later."

end

end

def post_to_twitter

Tweeter.new.post("New visitor! #{name} said #{content.first(50)}")

end

def record_ip_address

rate_limiter.record

end

def rate_limiter

@rate_limiter ||= UserContentRateLimiter.new(ip_address, :guestbook)

end

end

validate :ensure_content_not_spam, on: :create

validate :ensure_ip_address_not_rate_limited, on: :create

after_create :post_to_twitter

after_create :record_ip_address

private

def ensure_content_not_spam

if UserContentSpamChecker.new(content).spam?

errors[:content] << "Post rejected."

end

end

def ensure_ip_address_not_rate_limited

if rate_limiter.exceeded?

errors[:base] << "Please try again later."

end

end

def post_to_twitter

Tweeter.new.post("New visitor! #{name} said #{content.first(50)}")

end

def record_ip_address

rate_limiter.record

end

def rate_limiter

@rate_limiter ||= UserContentRateLimiter.new(ip_address, :guestbook)

end

end

This new version is only a couple of lines shorter than our original implementation but it knows much less about its constituent parts. Many of the details of the “how” these features are implemented have found a dedicated home in our domain with our model calling those collaborators to accomplish the larger task of creating a GuestbookEntry. These features are now independently testable and individually addressable. They are no longer locked in the context of creating a GuestbookEntry. At the meager cost of a few more files and some more code we now have simpler objects and a better set of interfaces. These objects can be changed with less risk of ripple effects and their interfaces can be called by other objects in the system.

Wrapping Up

“Good code invariably has small methods and small objects. I get lots of resistance to this idea, especially from experienced developers, but no one thing I do to systems provides as much help as breaking it into more pieces.” – Kent Beck, Smalltalk Best Practice Patterns

The Unix philosophy illustrates that small components that work together through an interface can be extraordinarily powerful. Nesting an aspect of your domain as an implementation detail of a specific model conflates responsibilities, bloats code, makes tests less isolated and slower, and hides concepts that should be first-class in your system.

Don’t let your domain concepts be shy. Promote them to full-fledged objects to make them more understandable, isolate and speed up their tests, reduce the likelihood that changes in neighboring features will have ripple effects, and provide the concepts a place to evolve apart from the rest of the system. The only thing we know with certainty about the futures of our systems is that they will change. We can design our systems to be more amenable to inevitable change by following the Unix philosophy and building clean interfaces between small objects that have one single responsibility.

One of the most common questions I received following my 7 Patterns to Refactor Fat ActiveRecord Models post was “Why are you using instances where class methods will do?”. I’d like to address that. Simply put:

I prefer object instances to class methods because class methods resist refactoring.

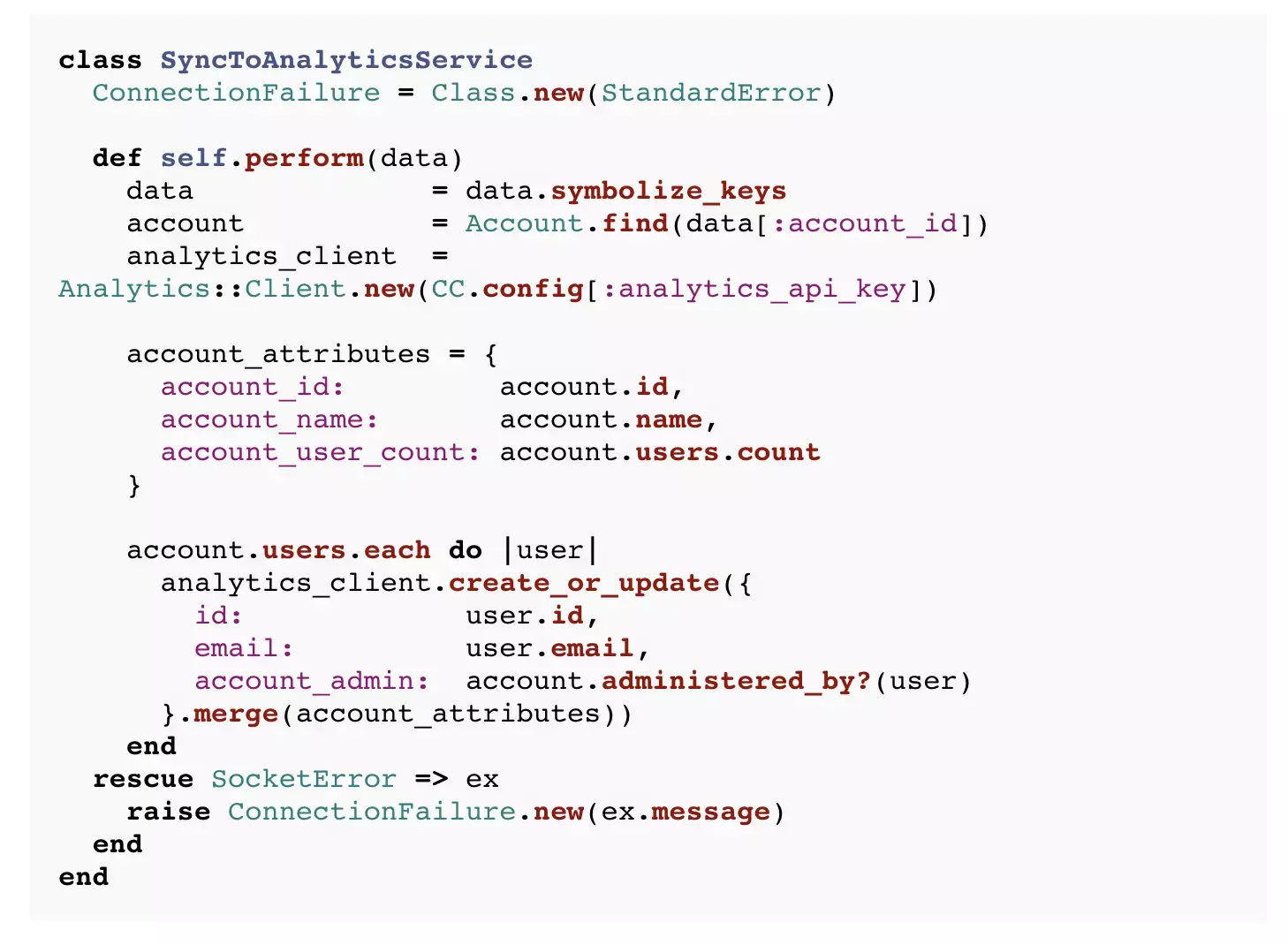

To illustrate, let’s look at an example background job for syncing data to a third-party analytics service:

The job iterates over each user sending a hash of attributes as an HTTP POST. If a SocketError is raised, it gets wrapped as a SyncToAnalyticsService::ConnectionFailure, which ensures it gets categorized properly in our error tracking system.

The SyncToAnalyticsService.perform method is pretty complex. It certainly has multiple responsibilities. The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) can be thought of as fractal, applying at a finer grained level of detail to all of applications, modules, classes and methods. SyncToAnalyticsService.perform is not a Composed Method because not all of the operations of the method are at the same level of abstraction.

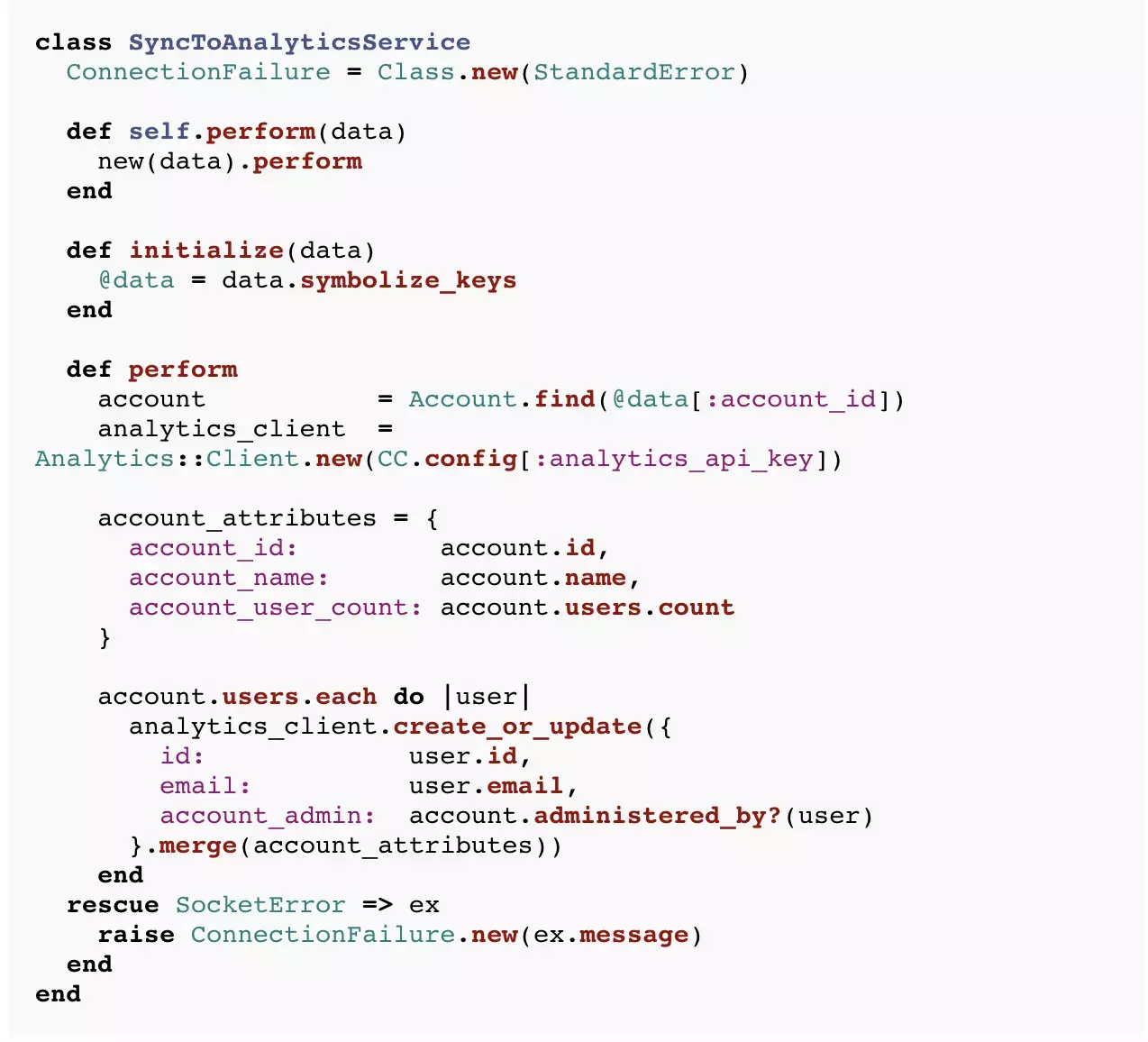

One solution would be to apply Extract Method a few times. You’d end up with something like this:

This is a little better the original, but doesn’t feel right. It’s certainly not object oriented. It feels like a weird hybrid of procedural and functional programming, stuck in an object-based world. Additionally, you can’t easily declare the extracted methods private because they are at the class level. (You’d have to switch to an ugly class << self form.)

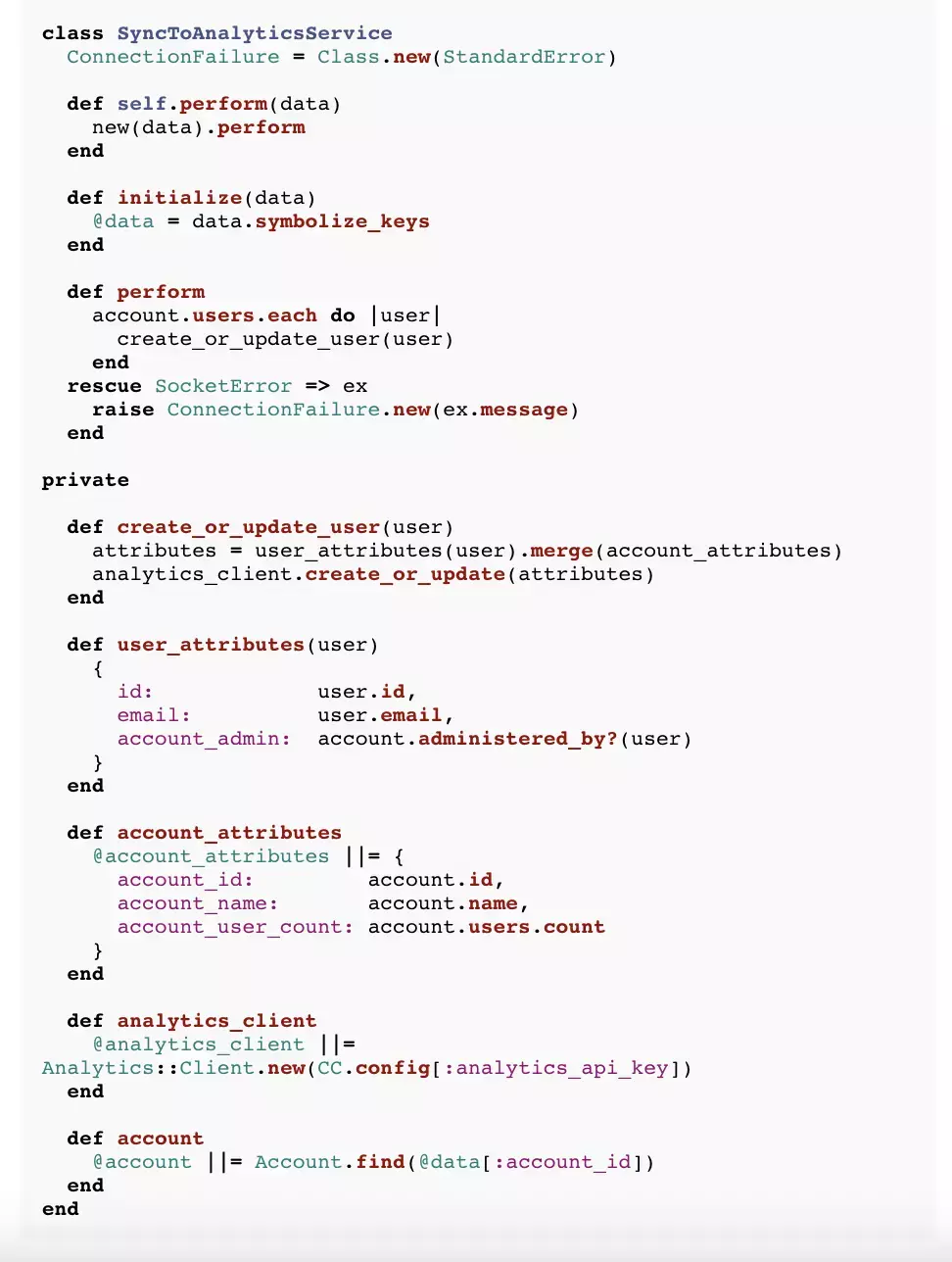

If I came across the original SyncToAnalyticsService implementation, I wouldn’t be eager to refactor only to end up with the above result. Instead, suppose we started with this:

Almost identical, but this time the functionality is in an instance method rather than a class method. Again, applying Extract Method we might end up with something like this:

Instead of adding class methods that have to pass around intermediate variables to get work done, we have methods like #account_attributes which memoize their results. I love this technique. When breaking down a method, extracting intermediate variables as memoized accessors is one of my favorite refactorings. The class didn’t start with any state, but as it was decomposed it was helpful to add some.

The result feels much cleaner to me. Refactoring to this feels like a clear win. There is now state and logic encapsulated together in an object. It’s easier to test because you can separate the creation of the object (Given) from the invokation of the action (When). And we’re not passing variables like the Account and Analytics::Client around everywhere.

Also, every piece of code that uses this logic won’t be coupled to the (global) class name. You can’t easily swap in new a class, but you can easily swap in a new instance. This encourages building up additional behavior with composition, rather than needing to re-open and expand classes for every change.

Refactoring note: I’d probably leave this class implemented as the last source listing shows. However, if the logic becomes more complex, this job is begging for a class to sync a single user to be split out.

So how does this relate to the premise of this article? I’m unlikely to see the opportunities for refactoring a class method because decomposing them produces ugly code. Starting with the instance form makes your refactoring options clear, and reduces friction to taking action on them. I’ve observed this effect many times in my own coding and also anecdotally across many Ruby teams over the years.

Objections

YAGNI (You Aren’t Going To Need It)

YANGI is an important principle, but misapplied in this case. If you open these classes in your editor, neither form is more or less complicated than the other. Saying “YAGNI an object here” is sort of like saying “YAGNI to indent with two spaces instead of a single tab.” The variants are only different stylistically. Applying YAGNI to object oriented design only make sense if there’s a difference in understandability (e.g. using one class versus two).

It Uses an Extra Object

Some people object on the basis that the instance form creates an additional object. That’s true, but in practice it doesn’t matter. Rails requests and background jobs create thousands upon thousands of Ruby objects. Optimizing object creation to lessen the stress on the Ruby garbage collector is a legitimate technique, but do it where it counts. You can only find out where it counts by measuring. It’s inconceivable that the single additional object that the instance variant creates will have a measurable impact on the performance of your system. (If you have a counter example with data, I’d love to hear about it.)

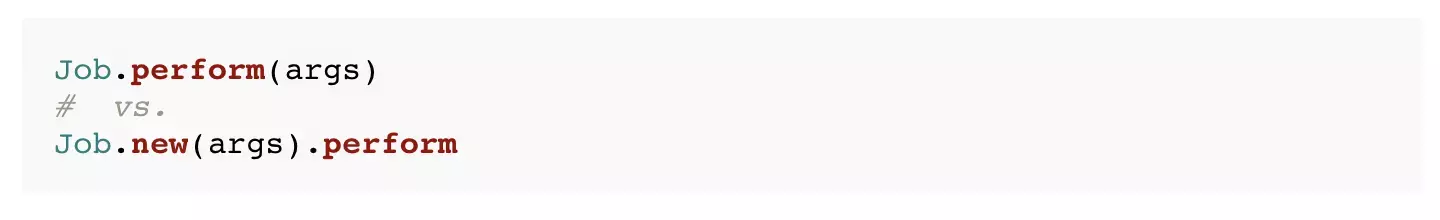

It’s Cumbersome to Call

Finally, some object that it is just easier to type:

That is true. In that case I simply define a convenience class method that builds the object and delegates down. In fact, that is one of the few cases I think class methods are okay. You can have your cake and eat it too, in this regard.

Wrapping Up

Begin with an object instance, even if it doesn’t have state or multiple methods right away. If you come back to change it later, you (and your team) will be more likely to refactor. If it never changes, the difference between the class method approach and the instance is negligible, and you certainly won’t be any worse off.

There are very few cases where I am comfortable with class methods in my code. They are either convenience methods, wrapping the act of initializing an instance and invoking a method on it, or extremely simple factory methods (no more than two lines), to allow collaborators to more easily construct objects.

What do you think? Which form do you prefer and why? Are there any pros/cons that I missed? Post a comment and let me know what you think!

P.S. If this sort of thing interests you, and you want to read more articles like it, you might like the Code Climate newsletter (see below). It’s just one email a month, and includes content about refactoring and object design with a Ruby focus.

Thanks to Doug Cole, Don Morrison and Josh Susser for reviewing this post.

When teams use Code Climate to improve the quality of their Rails applications, they learn to break the habit of allowing models to get fat. “Fat models” cause maintenance issues in large apps. Only incrementally better than cluttering controllers with domain logic, they usually represent a failure to apply the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP). “Anything related to what a user does” is not a single responsibility.

Early on, SRP is easier to apply. ActiveRecord classes handle persistence, associations and not much else. But bit-by-bit, they grow. Objects that are inherently responsible for persistence become the de facto owner of all business logic as well. And a year or two later you have a User class with over 500 lines of code, and hundreds of methods in it’s public interface. Callback hell ensues.

As you add more intrinsic complexity (read: features!) to your application, the goal is to spread it across a coordinated set of small, encapsulated objects (and, at a higher level, modules) just as you might spread cake batter across the bottom of a pan. Fat models are like the big clumps you get when you first pour the batter in. Refactor to break them down and spread out the logic evenly. Repeat this process and you’ll end up with a set of simple objects with well defined interfaces working together in a veritable symphony.

You may be thinking:

“But Rails makes it really hard to do OOP right!”

I used to believe that too. But after some exploration and practice, I realized that Rails (the framework) doesn’t impede OOP all that much. It’s the Rails “conventions” that don’t scale, or, more specifically, the lack of conventions for managing complexity beyond what the Active Record pattern can elegantly handle. Fortunately, we can apply OO-based principles and best practices where Rails is lacking.

Don’t Extract Mixins from Fat Models

Let’s get this out of the way. I discourage pulling sets of methods out of a large ActiveRecord class into “concerns”, or modules that are then mixed in to only one model. I once heard someone say:

“Any application with an app/concerns directory is concerning.”

And I agree. Prefer composition to inheritance. Using mixins like this is akin to “cleaning” a messy room by dumping the clutter into six separate junk drawers and slamming them shut. Sure, it looks cleaner at the surface, but the junk drawers actually make it harder to identify and implement the decompositions and extractions necessary to clarify the domain model.

Now on to the refactorings!

1. Extract Value Objects

Value Objects are simple objects whose equality is dependent on their value rather than an identity. They are usually immutable. Date, URI, and Pathname are examples from Ruby’s standard library, but your application can (and almost certainly should) define domain-specific Value Objects as well. Extracting them from ActiveRecords is low hanging refactoring fruit.

In Rails, Value Objects are great when you have an attribute or small group of attributes that have logic associated with them. Anything more than basic text fields and counters are candidates for Value Object extraction.

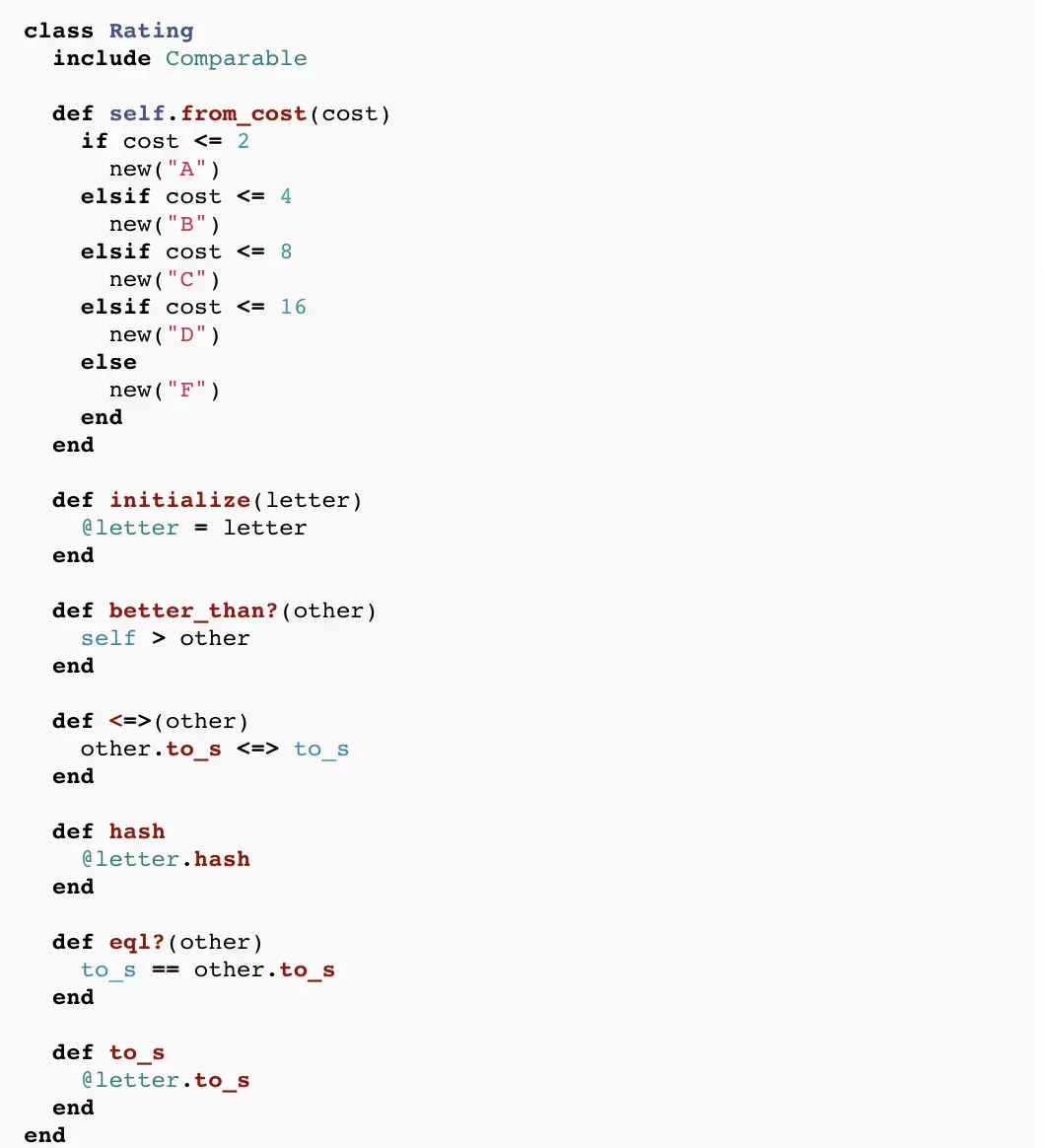

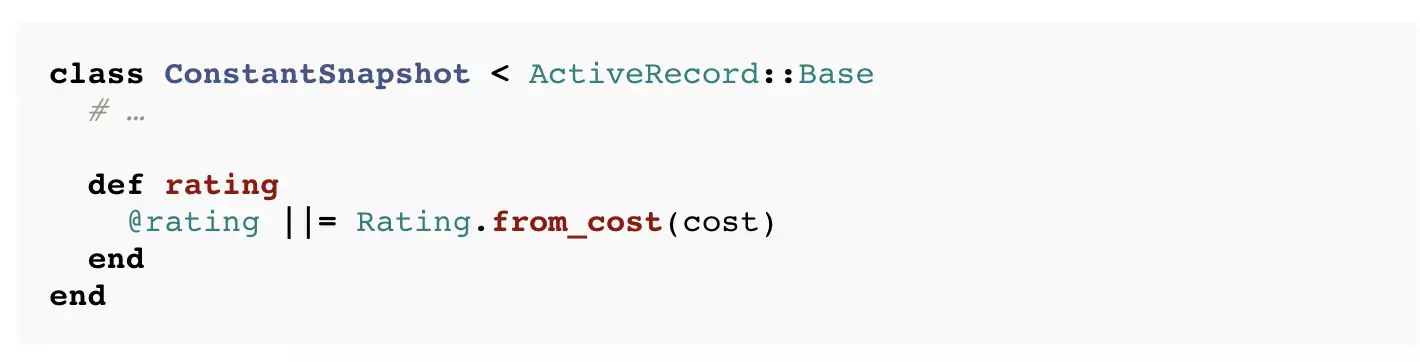

For example, a text messaging application I worked on had a PhoneNumber Value Object. An e-commerce application needs a Money class. Code Climate has a Value Object named Rating that represents a simple A - F grade that each class or module receives. I could (and originally did) use an instance of a Ruby String, but Rating allows me to combine behavior with the data:

Every ConstantSnapshot then exposes an instance of Rating in its public interface:

Beyond slimming down the ConstantSnapshot class, this has a number of advantages:

- The

#worse_than?and#better_than?methods provide a more expressive way to compare ratings than Ruby’s built-in operators (e.g.<and>). - Defining

#hashand#eql?makes it possible to use aRatingas a hash key. Code Climate uses this to idiomatically group constants by their ratings usingEnumberable#group_by. - The

#to_smethod allows me to interpolate aRatinginto a string (or template) without any extra work. - The class definition provides a convenient place for a factory method, returning the correct

Ratingfor a given “remediation cost” (the estimated time it would take to fix all of the smells in a given class).

2. Extract Service Objects

Some actions in a system warrant a Service Object to encapsulate their operation. I reach for Service Objects when an action meets one or more of these criteria:

- The action is complex (e.g. closing the books at the end of an accounting period)

- The action reaches across multiple models (e.g. an e-commerce purchase using

Order,CreditCardandCustomerobjects) - The action interacts with an external service (e.g. posting to social networks)

- The action is not a core concern of the underlying model (e.g. sweeping up outdated data after a certain time period).

- There are multiple ways of performing the action (e.g. authenticating with an access token or password). This is the Gang of Four Strategy pattern.

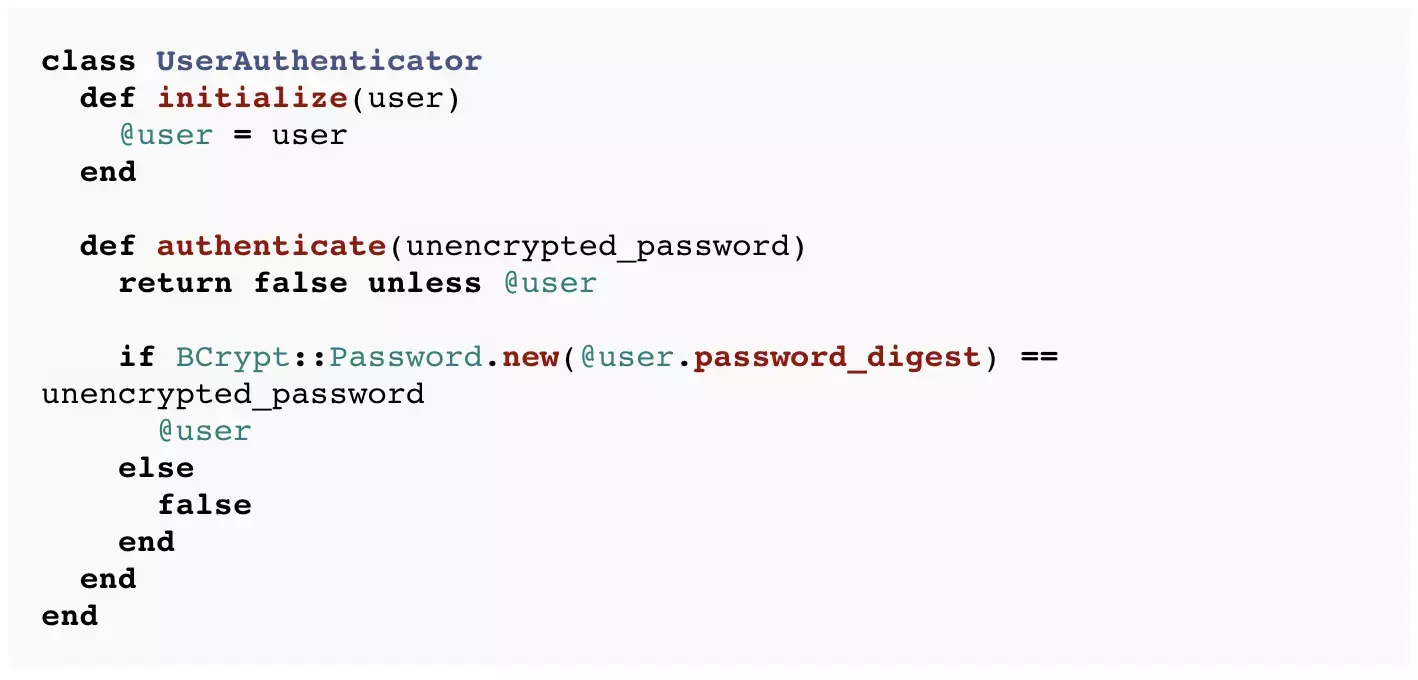

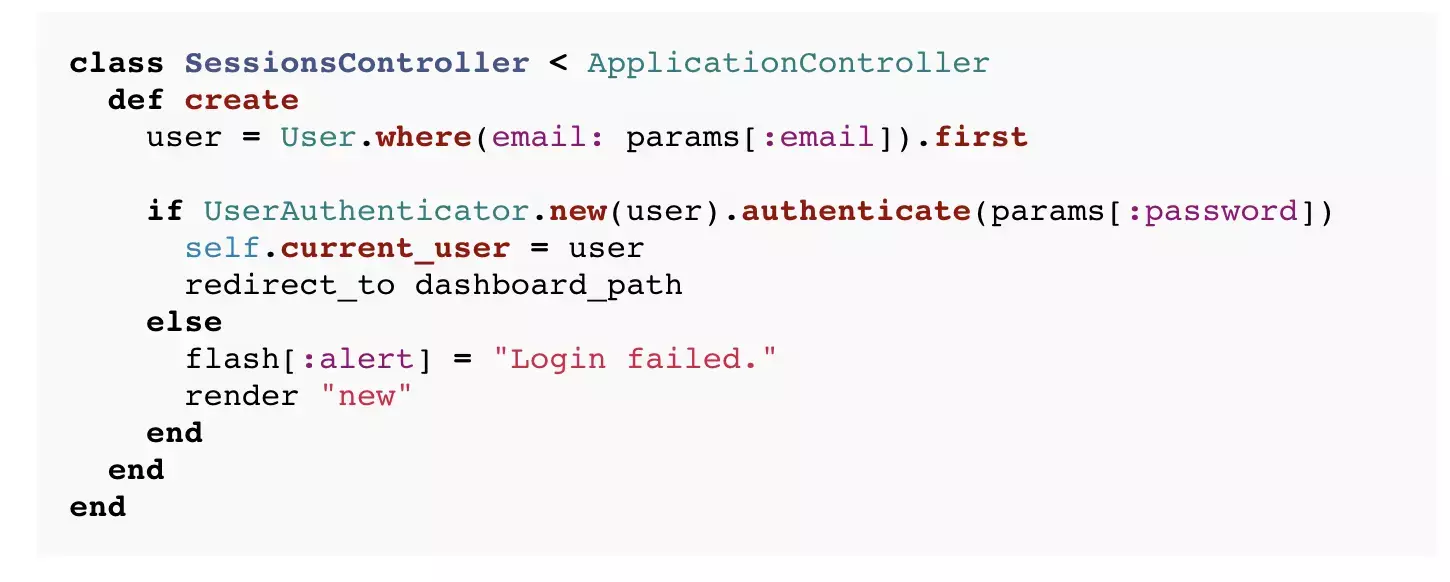

As an example, we could pull a User#authenticate method out into a UserAuthenticator:

And the SessionsController would look like this:

3. Extract Form Objects

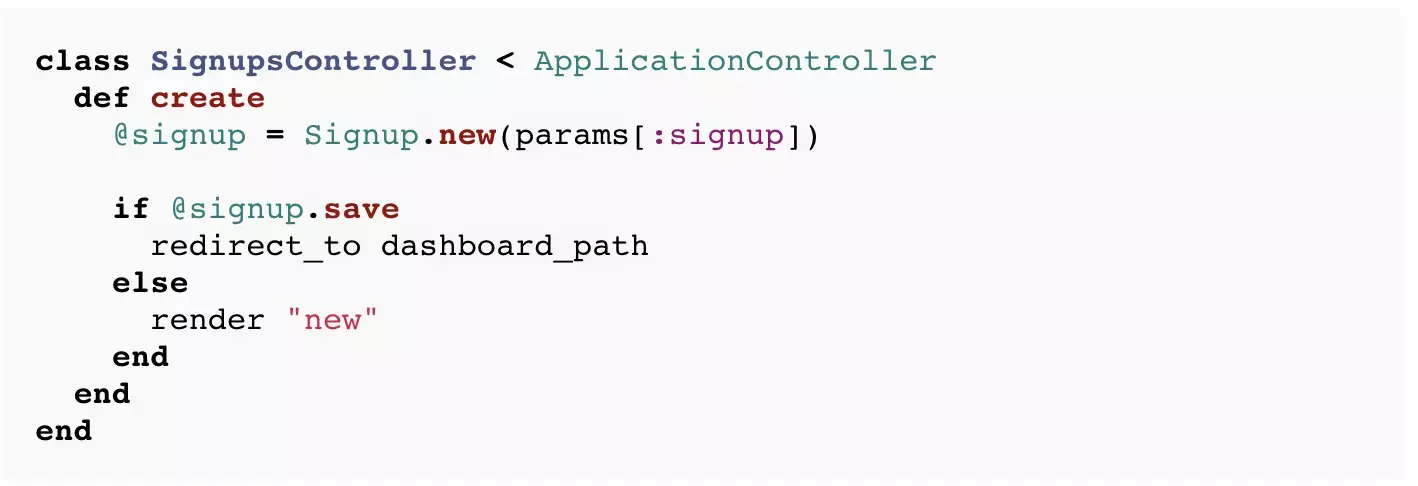

When multiple ActiveRecord models might be updated by a single form submission, a Form Object can encapsulate the aggregation. This is far cleaner than using accepts_nested_attributes_for, which, in my humble opinion, should be deprecated. A common example would be a signup form that results in the creation of both a Company and a User:

I’ve started using Virtus in these objects to get ActiveRecord-like attribute functionality. The Form Object quacks like an ActiveRecord, so the controller remains familiar:

This works well for simple cases like the above, but if the persistence logic in the form gets too complex you can combine this approach with a Service Object. As a bonus, since validation logic is often contextual, it can be defined in the place exactly where it matters instead of needing to guard validations in the ActiveRecord itself.

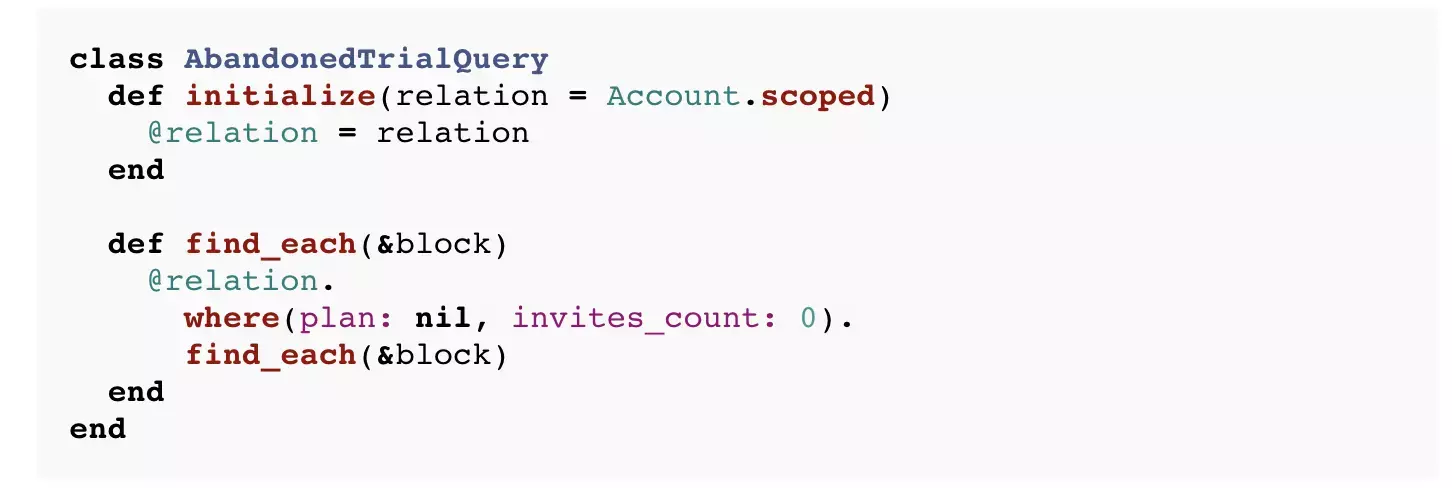

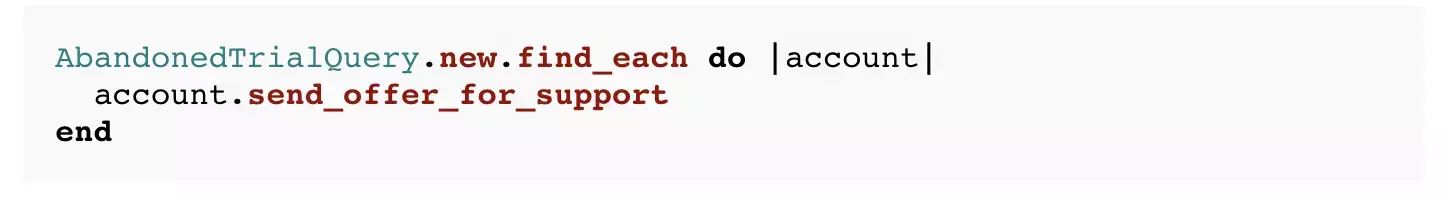

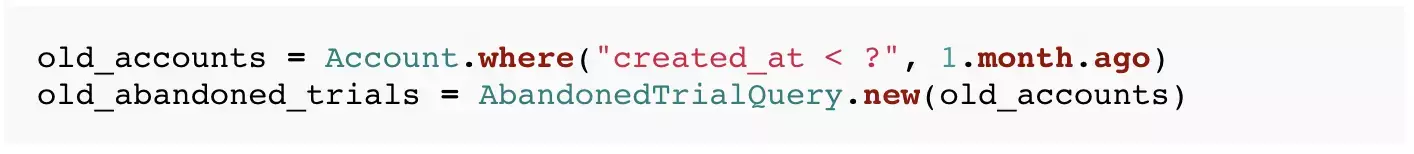

4. Extract Query Objects

For complex SQL queries littering the definition of your ActiveRecord subclass (either as scopes or class methods), consider extracting query objects. Each query object is responsible for returning a result set based on business rules. For example, a Query Object to find abandoned trials might look like this:

You might use it in a background job to send emails:

Since ActiveRecord::Relation instances are first class citizens as of Rails 3, they make a great input to a Query Object. This allows you to combine queries using composition:

Don’t bother testing a class like this in isolation. Use tests that exercise the object and the database together to ensure the correct rows are returned in the right order and any joins or eager loads are performed (e.g. to avoid N + 1 query bugs).

5. Introduce View Objects

If logic is needed purely for display purposes, it does not belong in the model. Ask yourself, “If I was implementing an alternative interface to this application, like a voice-activated UI, would I need this?”. If not, consider putting it in a helper or (often better) a View object.

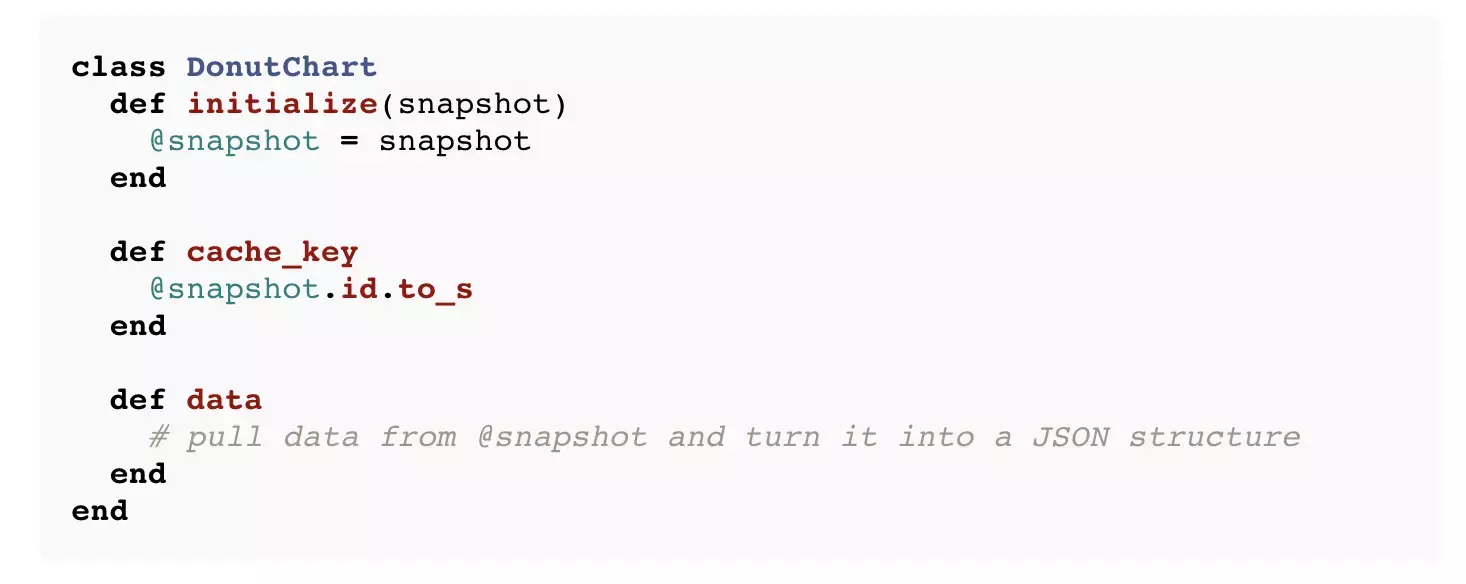

For example, the donut charts in Code Climate break down class ratings based on a snapshot of the codebase (e.g. Rails on Code Climate) and are encapsulated as a View:

I often find a one-to-one relationship between Views and ERB (or Haml/Slim) templates. This has led me to start investigating implementations of the Two Step View pattern that can be used with Rails, but I don’t have a clear solution yet.

Note: The term “Presenter” has caught on in the Ruby community, but I avoid it for its baggage and conflicting use. The “Presenter” term was introduced by Jay Fields to describe what I refer to above as “Form Objects”. Also, Rails unfortunately uses the term “view” to describe what are otherwise known as “templates”. To avoid ambiguity, I sometimes refer to these View objects as “View Models”.

6. Extract Policy Objects

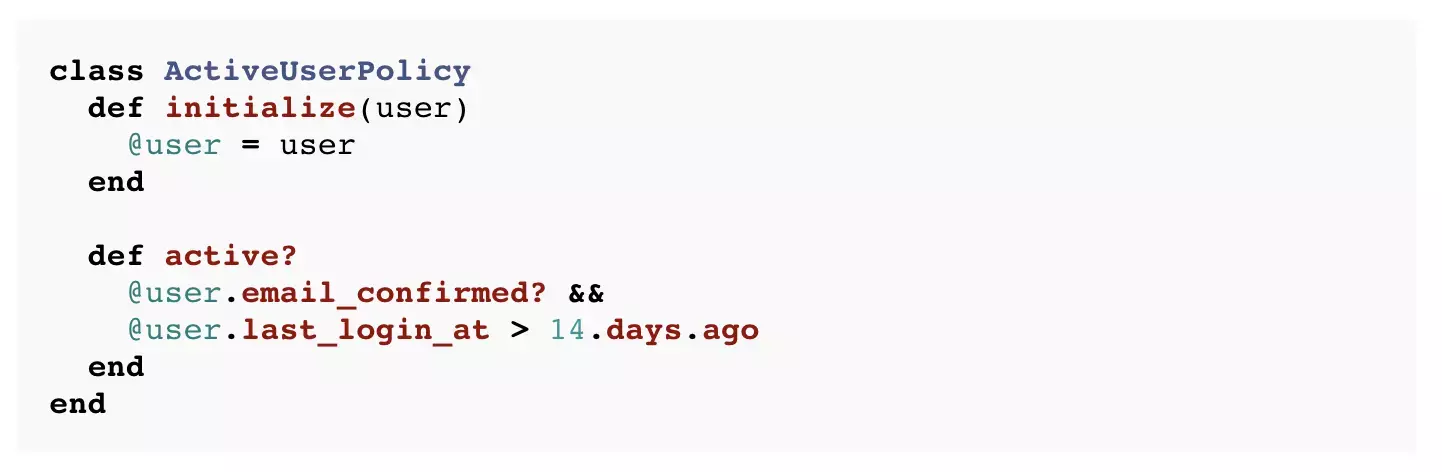

Sometimes complex read operations might deserve their own objects. In these cases I reach for a Policy Object. This allows you to keep tangential logic, like which users are considered active for analytics purposes, out of your core domain objects. For example:

This Policy Object encapsulates one business rule, that a user is considered active if they have a confirmed email address and have logged in within the last two weeks. You can also use Policy Objects for a group of business rules like an Authorizer that regulates which data a user can access.

Policy Objects are similar to Service Objects, but I use the term “Service Object” for write operations and “Policy Object” for reads. They are also similar to Query Objects, but Query Objects focus on executing SQL to return a result set, whereas Policy Objects operate on domain models already loaded into memory.

7. Extract Decorators

Decorators let you layer on functionality to existing operations, and therefore serve a similar purpose to callbacks. For cases where callback logic only needs to run in some circumstances or including it in the model would give the model too many responsibilities, a Decorator is useful.

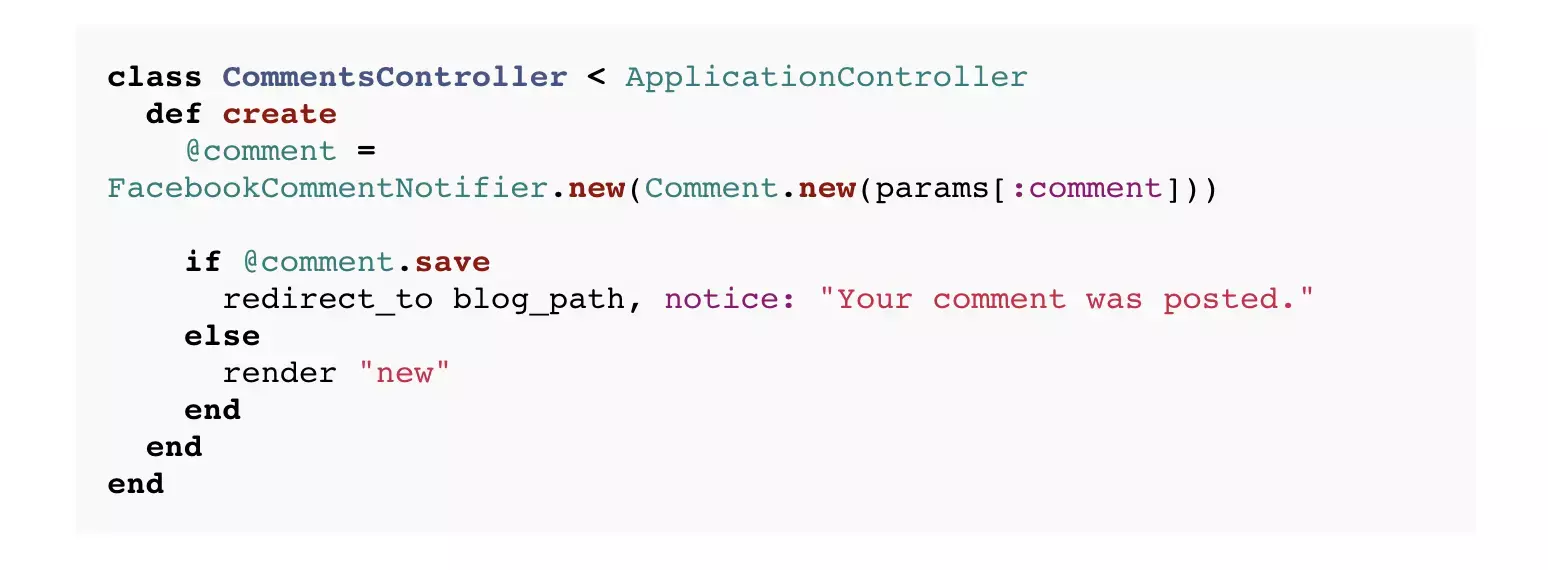

Posting a comment on a blog post might trigger a post to someone’s Facebook wall, but that doesn’t mean the logic should be hard wired into the Comment class. One sign you’ve added too many responsibilities in callbacks is slow and brittle tests or an urge to stub out side effects in wholly unrelated test cases.

Here’s how you might extract Facebook posting logic into a Decorator:

And how a controller might use it:

Decorators differ from Service Objects because they layer on responsibilities to existing interfaces. Once decorated, collaborators just treat the FacebookCommentNotifier instance as if it were a Comment. In its standard library, Ruby provides a number of facilities to make building decorators easier with metaprogramming.

Wrapping Up

Even in a Rails application, there are many tools to manage complexity in the model layer. None of them require you to throw out Rails. ActiveRecord is a fantastic library, but any pattern breaks down if you depend on it exclusively. Try limiting your ActiveRecords to persistence behavior. Sprinkle in some of these techniques to spread out the logic in your domain model and the result will be a much more maintainable application.

You’ll also note that many of the patterns described here are quite simple. The objects are just “Plain Old Ruby Objects” (PORO) used in different ways. And that’s part of the point and the beauty of OOP. Every problem doesn’t need to be solved by a framework or library, and naming matters a great deal.

What do you think of the seven techniques I presented above? What are your favorites and why? Have I missed any? Let me know in the comments!

P.S. If you found this post useful, you may want to subscribe to our email newsletter (see below). It’s low volume, and includes content about OOP and refactoring Rails applications like this.

Further Reading

- Crazy, Heretical, and Awesome: The Way I Write Rails Apps

- ActiveRecord (and Rails) Considered Harmful

Thank you to Steven Bristol, Piotr Solnica, Don Morrison, Jason Roelofs, Giles Bowkett, Justin Ko, Ernie Miller, Steve Klabnik, Pat Maddox, Sergey Nartimov and Nick Gauthier for reviewing this post.