Productivity

For organizations looking to fine-tune their DevOps practices or understand where they should improve to excel, DORA metrics are an essential starting point. Code Climate Velocity now surfaces the four DORA metrics in our Analytics module, allowing engineering leaders to share the state of their DevOps outcomes with the rest of the organization, identify areas of improvement, establish goals, and observe progress towards those goals.

When used thoughtfully, DORA metrics can help you understand and improve your engineering team’s speed and stability. Here’s how Code Climate Velocity delivers the most accurate and reliable measurements for each metric, and how to maximize their impact in your organization.

What is DORA?

The DORA metrics were defined by the DevOps Research & Assessment group, formed by industry leaders Nicole Forsgren, Jez Humble, and Gene Kim. These metrics, along with their performance benchmarks, were largely popularized by the book Accelerate, co-authored by the DORA group. Not only do they represent the most critical areas in the DevOps process, they’re also the metrics most statistically correlated with a company’s organizational performance.

What are the four DORA metrics?

The four DORA metrics fall under two categories:

Stability Metrics (Measuring the impact of incidents in production):

- Change Failure Rate: The percentage of deployments causing a failure in production.

- Mean Time to Recovery: How long, on average, it takes to recover from a failure in production.

Speed Metrics (Measuring the efficiency of your engineering processes):

- Deploy Frequency: How frequently the engineering team is deploying code to production.

- Mean Lead Time for Changes: The time it takes to go from code committed to code successfully running in production.

How Velocity Does DORA Differently

While many leaders rely on homegrown calculations to surface their DORA metrics, a tool like Velocity allows teams to get even more out of DORA. Not only do we help teams standardize measurement and ensure accuracy, we also make it possible for leaders to go a level deeper — digging into the aspects of the SDLC that influence DORA metrics, so they can identify specific opportunities for high-impact changes.

Our approach to DORA metrics is unique because:

We use the most accurate data

Velocity uses our customers’ real incident and deployment data, through Velocity’s curl command, to ingest data from JIRA and our Incidents API, for accurate calculations of each metric.

Many platforms rely on proxy data as they lack integration with incident tools. Yet this approach yields lower quality, error-prone insights, which can lead to inaccurate assessments of your DevOps processes.

You can view trends over time

The Velocity Analytics module gives users the ability to see DORA Metrics trend over time, allowing you to select specific timeframes, including up to a year of historical data.

You can use annotations to add context and measure the impact of organizational changes on your processes

Additionally, users can use annotations to keep a record of changes implemented, allowing you to understand and report on their impact. For example, if your team recently scaled, you can note that as an event on a specific day in the Analytics module, and observe how that change impacted your processes over time. Reviewing DORA metrics after growing your team can give you insight into the impact of hiring new engineers or the efficacy of your onboarding processes.

You can surface DORA metrics alongside Velocity metrics

The platform also allows customers to surface these four metrics in tandem with non-DORA metrics.

Why is this important? DORA metrics measure outcomes — they help you determine where to make improvements, and where to investigate further. With these metrics surfaced in Analytics, it’s now easier for engineering leaders to investigate. Users can see how other key SDLC metrics correlate with DORA metrics, and pinpoint specific areas for improvement.

For example, viewing metrics in tandem may reveal that when you have a high number of unreviewed PRs, your Change Failure Rate is also higher than usual. With that information, you have a starting point for improving CFR, and can put in place processes for preventing unreviewed PRs from making it to production.

Engineering leaders can coach teams to improve these metrics, like reinforcing good code hygiene and shoring up CI/CD best practices. Conversely, if these metrics comparisons indicate that things are going well for a specific team, you can dig in to figure out where they’re excelling and scale those best practices.

Metrics offer concrete discussion points

DORA metrics are one tool engineering leaders can use to gain a high level understanding of their team’s speed and stability, and hone in on areas of their software delivery process that need improvement. With these insights, leaders can have a significant impact on the success of the business.

Sharing these discoveries with your engineering team is an excellent way to set the stage for retrospectives, stand ups, and 1-on-1s. With a deeper understanding of your processes, as well as areas in need of improvement or areas where your team excels, you can inform coaching conversations, re-allocate time and resources, or extrapolate effective practices and apply them across teams.

Leaders can also use these insights in presentations or conversations with stakeholders in order to advocate for their team, justify resource requests, and demonstrate the impact of engineering decisions on the business.

Ready to start using DORA metrics to gain actionable insights to improve your DevOps processes? Speak with a Velocity product specialist.

Performance reviews in engineering are often tied to compensation. End-of-year and mid-point check-ins can be great opportunities to discuss individual goals and foster professional growth, but too often they are used as ways to assess whether direct reports are eligible for raises or promotions based on their ability to hit key metrics.

For engineering leaders, a more valuable way to use performance reviews is as a structured opportunity to have a conversation about a developer’s progress and work with them to find ways to grow in their careers through new challenges. This benefits both developers and organizations as a whole — developers are able to advance their skills, and companies are able to retain top engineers who are continually evolving. Even senior engineers look for opportunities for growth, and are more likely to stay at an organization that supports and challenges them.

The key to achieving this is by focusing on competency, rather than productivity measurements, when it comes to evaluating compensation and performance. But how do we define competency in engineering?

What is competency in engineering?

Where productivity might measure things like lines of code, competency looks at how an engineer approaches a problem, collaborates with their team to help move things forward, and takes on new challenges.

Questions to consider when evaluating a developer’s competency might include:

- How thoughtful are their comments in a Code Review?

- Do they make informed decisions based on data?

- How do they navigate failure?

- How do they anticipate or respond to change?

Engineering leader Dustin Diaz created a reusable template for evaluating competency in engineering, which he links to in this post. The template borrows from concepts in The Manager’s Path, by author and engineering leader Camille Fournier, and is modeled after the SPACE framework, and outlines levels of competency for engineers at different levels of seniority. The matrix can be helpful for leaders looking to hone in on areas like collaboration, performance, and efficiency/quality. It includes markers of competency for different tiers of engineers, including anticipating broad technical change, end-to-end responsibility on projects, and taking initiative to solve issues.

Performance review essentials

We’ve addressed how performance reviews during a difficult year can be especially challenging. Yet no matter the circumstances, there are principles of a successful performance review that will always be relevant.

Reviews should always include:

- Compassion and empathy — With the understanding that employees could be under a lot of stress, a performance review shouldn’t add to any pressure they’re experiencing.

- Specific units of work — In order to provide useful feedback, bring examples of work to discuss during a review. By focusing on the work itself, the review remains objective, and can open the door for a coaching conversation.

- Objective data to check biases — There are many common performance review biases, as well as ways to correct for them by contextualizing data, checking assumptions, and taking circumstance into account. It’s important not to let unconscious biases inform your analysis of a developer’s work.

Aligning developer and company incentives

When performance reviews are based on hitting productivity benchmarks that are implicitly linked to compensation, developers might be less focused on ambitious goals and more on checking boxes that they believe will earn them a raise; rather than challenging themselves, they will likely be incentivized to play it safe with easy-to-achieve goals.

Encouraging a focus on competency invites engineers to make decisions that have more potential to move the needle in an organization, and to take risks, even if they could lead to failure.

During our webinar on data-driven leadership, Sophie Roberts, Director of Engineering at Shopify shared why rewarding productivity over growth could have adverse effects: “You end up in a situation where people want to get off projects that they don’t really think they have executive buy-in, or try and game the work they’re doing,” Roberts said. “I’ve canceled people’s projects and promoted them the next month, because how they were approaching the work was what we expect from a competency level of people who are more senior…They may try to get work that is a more sure shot of moving a metric because they think that’s what’s going to result in their promotion or their career progression.”

An emphasis on competency can improve the following:

- Risk-taking. If engineering leaders foster psychological safety within teams, developers are more likely to take risks without the fear of being penalized for failure. If metrics are not tied to compensation, developers will likely be more ambitious with their goal-setting.

- Flexibility and adaptability. Failure and change are both inevitable in engineering organizations. Instead of trying to avoid mistakes, emphasize the importance of learning and of implementing thoughtful solutions that can have a lasting impact.

- Upskilling and developer retention. Investing in the professional development of an engineer is a vote of confidence in their abilities. Engineering leaders can boost retention through upskilling or by enabling individuals to grow into more senior positions.

Using metrics to assess competency

Data-driven insights can provide engineering leaders with objective ways to evaluate developer competency, without tying metrics directly to compensation. They can help you assess a developer’s progress, spot opportunities for improvement, and even combat common performance review biases.

One effective way to use metrics in performance reviews is to quantify impact. In our webinar on data-driven performance reviews, Smruti Patel, now VP of Engineering at Apollo, shared how data helps IC’s on her team recognize their impact on the business during self-evaluations.

“It comes down to finding the right engineering data that best articulates impact to the team and business goals. So if you think about it, you can use a very irrefutable factor, say, ‘I shipped X, which reduced the end-to-end API latency from 4 or 5 seconds to 2.5 seconds. And this is how it impacted the business,” she said.

In the same discussion, Katie Wilde, now Senior Director of Engineering at Snyk Cloud, shared how metrics explained a discrepancy between one engineer’s self-evaluation and her peer reviews. This engineer gave herself a strong rating, but her peers did not rate her as highly. When Wilde dug into the data, she found that it was not a case of the individual being overconfident, but a case of hidden bias — the engineer’s PRs were being scrutinized more heavily than those of her male counterparts.

In both instances, data helped provide a more complete picture of a developer’s abilities and impact, without being directly tied to performance benchmarks or compensation.

Defining success in performance reviews

Overall, metrics are able to provide concrete data to counteract assumptions, both on the part of the reviewer and the engineers themselves. By taking a holistic approach to performance reviews and contextualizing qualitative and quantitative data, including having one-on-one conversations with developers, leaders can make more informed decisions about promotions and compensation for their teams.

Keep in mind that performance reviews should be opportunities to encourage growth and career development for engineers, while gaining feedback that can inform engineering practices.

Most importantly, rewarding competency is an effective way to align developer goals with business goals. This way, leaders are invested in the growth of valuable members of their team who make a significant impact, while engineers are recognized for their contributions and able to grow in their careers.

Ten years ago, very few people tracked their steps, heart rate, or sleep. Sure, pedometers existed, as did heart rate monitors and clunky sleep monitors, but they weren’t particularly commonplace. Now, it’s not uncommon to know how many steps you’ve taken in a day, and many people sport metal and plastic on their wrists that monitor their activity, heart rate, and sleep quality.

What changed?

In the past, that information was inconvenient to access, and found in disparate places. Nowadays, fitness trackers and smart watches bring together all of that data so we can tap into it to make decisions.

Imagine this: I sit at my desk all day. I glance down at my fitness tracker and it says I’ve only taken 100 steps today. I feel really tired. What do I do? Take a walk? Drink another cup of coffee? Let’s say I take a walk. Awesome! A quick stroll to the park after lunch and I’ve reached my step goal of 8,000 steps! I feel great. I sleep well and my tracker says I got 8 hours.

The next day, faced with the same afternoon drowsiness, I skip the walk and opt for a second coffee. I sleep poorly, and when I wake up, I see that I only got 4 hours of sleep.

On the third day, instead of reaching for some caffeine, I choose to take a walk. It was a data-informed choice. Without the data, I might have ruined my sleep schedule by again drinking coffee too late in the day and later wondering why I felt so tired.

So, what does this have to do with engineering data? Ten years ago, the process of gathering engineering data involved a mishmash of spreadsheets, gut feel, and self-evaluation. Leaders faced a black hole with no easily accessible information in one place.

Code Climate Velocity changes that. Now, it’s possible to view trends from the entire software development lifecycle in one place without having to wrangle reports from Jira or comb through Github. Putting everything together not only makes the data more accessible, it makes it easier to make informed decisions.

Let’s say I want to boost code quality by adding second code reviews to my coding process. Sounds great, right? More eyes on the code is better? Not quite. The data we’ve gathered from thousands of engineering organizations shows that multiple review processes tend to negatively impact speed to market. Why? Naturally, by adding an additional step to the process, things take longer.

But what if those second reviews lead to higher code quality? Code Climate Velocity gives you insight into things like Defect and Rework Rates, which can validate whether quality increases by implementing second reviews. If the data within Velocity were to show that Cycle Time increases and second reviews have no effect on Defect Rate (or worse, if they increase Defect Rate), then maybe we shouldn’t have that second cup of coffee…er, second code review.

This is exactly the situation I ran into with a client of ours. A globally distributed engineering organization, they required two reviews as part of their development process. The second review typically depended on someone located multiple time zones ahead of or behind the author of the pull request. As a result, the team’s Cycle Time spanned multiple weeks, held up by second reviews that were often just a thumbs up. By limiting second reviews, the organization would save upwards of 72 hours per PR, cutting their Cycle Time in half. They would also be able to track their Defect Rate and Rework Rate to ensure there were no negative changes in code quality.

We don’t want to know that drinking a second cup of coffee correlates with poor sleep — that is scary. But by being alerted to that fact, we are able to make informed decisions about what to do and how to change our behaviors. Then, we can measure outcomes and assess the efficacy of our choices.

There is a common misconception that applying metrics to engineering is scary — that it will be used to penalize people who don’t meet arbitrary goals. Just as smart watches don’t force you to take steps, engineering data doesn’t force your hand. Code Climate Velocity presents you with data and insights from your version control systems, project management systems, and other tools so that you can make data-informed choices to continue or change course and then track the outcome of those choices. Like fitness and sleep data, engineering data is a tool. A tool that can have immense value when used thoughtfully and responsibly.

Now, go reward yourself with some more steps! We’ve brought the wonderful world of data into our everyday lives, why not into engineering?

To find out what kinds of decisions a Software Engineering Intelligence platform like Velocity can help inform, reach out to one of our specialists.

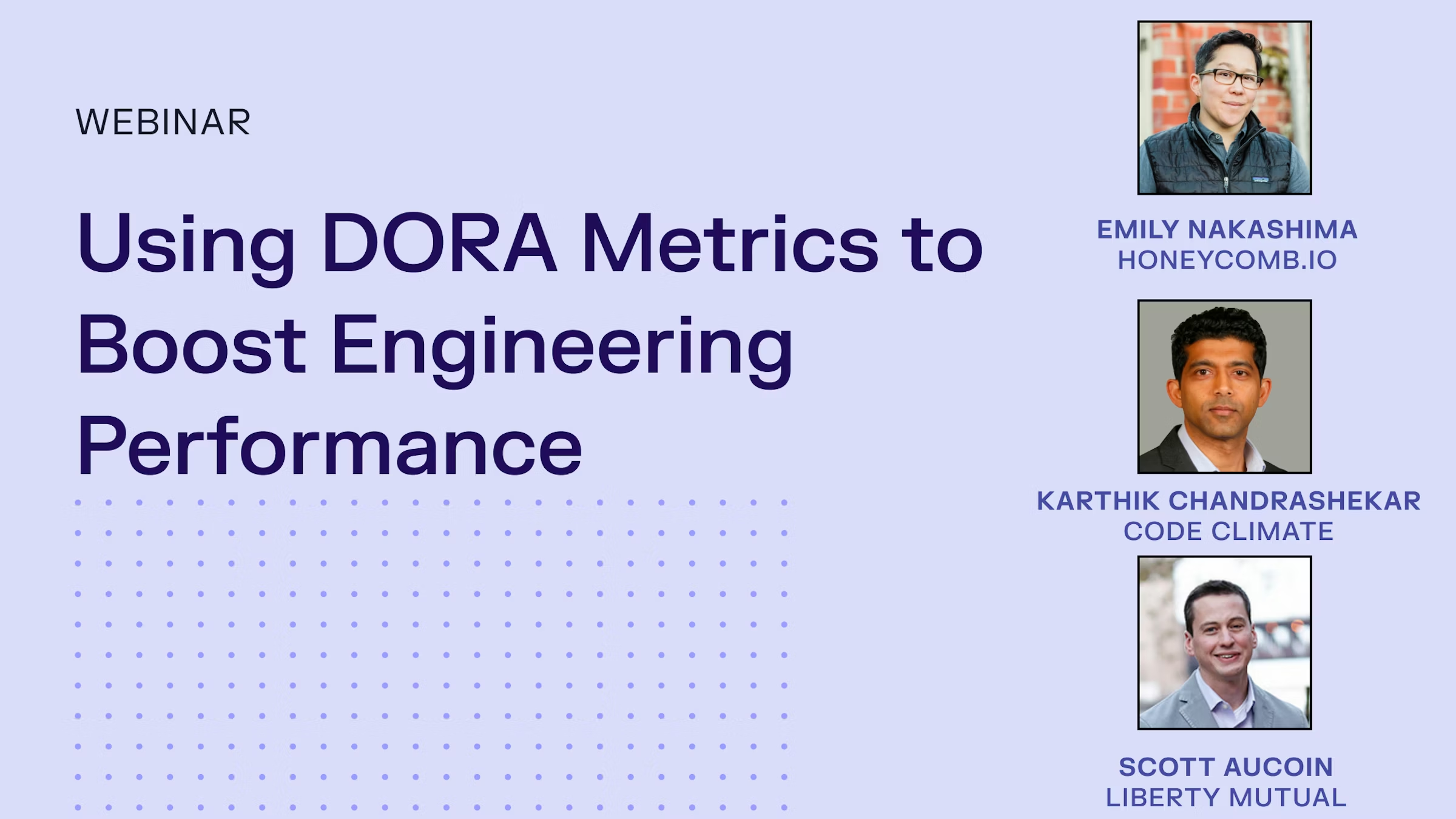

What’s the practical value of DORA metrics, and how are real engineering organizations using them? To find out, we invited a panel of engineering leaders & industry experts to share their experiences.

Code Climate Senior Product Manager Madison Unell moderated the conversation, which featured:

- Scott Aucoin, Technology Director at Liberty Mutual

- Emily Nakashima, VP of Engineering at Honeycomb

- Karthik Chandrashekar, SVP of Customer Organizations at Code Climate

Over 45 minutes, these panelists discussed real-world experiences using DORA metrics to drive success across their engineering organizations.

Below are some of the key takeaways, but first, meet the panelists:

Scott Aucoin: I work at Liberty Mutual. We’ve got about 1,000 technology teams around the world. We’ve been leveraging DORA metrics for a while now. I wouldn’t say it’s perfect across the board, but I’ll talk about how we’ve been leveraging them. The role that I play is across about 250 teams working on our Agile enablement, just improving our agility, improving things like DevOps and the way that we operate in general; and our portfolio management work…from strategy through execution; and user experience to help us build intuitively-designed things, everything from the frontend of different applications to APIs. So finding ways to leverage DORA throughout those three different hats, it’s been awesome, and it’s really educating for me.

Emily Nakashima: I’m the VP of Engineering at a startup called Honeycomb. I manage an engineering team of just about 40 people, and we’re in the observability space. So basically, building for other developers, which is a wonderful thing. And we had been following along with DORA from the early days and have been enthusiasts and just made this switch over to using the metrics ourselves. So I’m excited to talk about that journey.

Karthik Chandrashekar: I’m the Senior VP of our Customer Organization at Code Climate. I have this cool job of working with all our engineering community customers solving and helping them with their data-driven engineering challenges. DORA is fascinating because I started out as a developer myself many years back, but it’s great to see where engineering teams are going today in a measurement and management approach. And DORA is central to that approach in many of the customer organizations I interact with. So I’m happy to share the insights and trends that I see.

Why did your organization decide to start using DORA?

Emily Nakashima: I first came to DORA metrics from a place of wanting to do better because we’re in the DevOps developer tooling space ourselves. Our executive team was familiar with the DORA metrics, and we had used them for years to understand our customers, using them as a tool to understand where people were in their maturity and how ready they would be to adopt our product…we had this common language around DORA…[At the same time,] our engineering team was amazing, and we weren’t getting the credit for it that we deserved. And by starting to frame our performance around the DORA metrics and show that we were DORA Elite on all these axes, I think it was a really valuable tool for helping to paint that story in a way that felt more objective rather than just me going, “We’ve got a great team.” And so far, honestly, it’s been pretty effective.

Scott Aucoin: Liberty Mutual being a 110-year-old insurance company, there are a lot of metrics. There are some metrics that I think we might say, “Okay, those are a little bit outdated now.” And then there are other ones that the teams use because they’re appropriate for the type of work the teams are doing. What we found to be really valuable about DORA metrics is their consistency…and the ability to really meet our customers and their needs through leveraging DORA metrics.

Karthik Chandrashekar: Speaking with a lot of CTOs and VPs of different organizations, I think there’s a desire to be more and more data-driven. And historically, that has been more around people, culture, teams, all of that, but now that’s transcended to processes and to data-driven engineering.

How did you go about securing buy-in?

Scott Aucoin: This has been pretty grassroots for us. We’ve got about 1,000 technology teams across our organization. So making a major shift is going to be a slow process. And in fact, when it’s a top-down shift, sometimes there’s more hesitancy or questioning like, “Why would we do this just because this person said to do this?” Now, all of a sudden, it’s the right thing to do. So instead, what we’ve been doing and what’s happened in different parts of our organization is bringing along the story of what DORA metrics can help us with.

Emily Nakashima: The thing I love about Scott’s approach is that it was a top-down idea, but he really leveraged this bottom-up approach, starting with practitioners and getting their buy-in and letting them forge the way and help figure out what was working rather than dictating that from above. I think that it’s so important to really start with your engineers and make sure that they understand what and why. And I think a lot of us have seen the engineers get very rightly a little nervous about the idea of being measured. And I think that’s super-legitimate because there’s been so many bad metrics that we’ve used in the past to try to measure engineering productivity, like Lines of code, or PRs Merged. I think we knew we would encounter some of that resistance and then just a little bit of concern from our engineering teams about, what does it mean to be measured? And honestly, that’s something we’re still working through. I think the things that really helped us were, one, being really clear about the connection to individual performance and team performance and saying, we really think about these as KPIs, as health metrics that we’re using to understand the system, rather than something we’re trying to grade you on or assess you on. We also framed it as an experiment, which is something our culture really values.

DORA’s performance buckets are based on industry benchmarks, but you’re all talking about measuring at the company level. How do you think about these measures within your company?

Emily Nakashima: This was absolutely something that was an internal debate for us. When I first proposed using these, actually, our COO Jeff was a proponent of the idea as well. So the two of us were scheming on this, but there was really resistance that people pointed out that the idea of these metrics was about looking at entire cohorts. And there was some real debate as to whether they were meaningful on the individual team or company level. And we are the engineering team that just likes to supplement disagreements with data. So we just said, that might be true, let’s try to measure them and see where it goes. And I will say they are useful for helping us see where we need to look in more detail. They don’t necessarily give you really granular specifics about what’s going wrong with a specific team or why something got better or worse. But I do think that they have had a value just for finding hotspots or seeing trends before you might have an intuition that the trend is taking place. Sometimes you can start to see it in the data, but I think it was indeed a valid critique, ’cause we’re, I think, using them in a way that they’re not designed for.

Something important about the DORA metrics that I think is cool is that each time they produce the report, the way they set the Elite and High and other tiers can change over time. And I like that. And you also see a lot of movement between the categories…And to me, it’s a really good reminder that as engineering teams, if we just keep doing the same thing over and over and don’t evolve our practices, we fall behind the industry and our past performance.

Scott Aucoin: I look at the DORA metrics with the main intent of ensuring that our teams are learning and improving and having an opportunity to reflect in a different way than they’re used to. But also, because of my competitive nature, I look at it through the lens of how we are doing, not just against other insurance companies, which is critical, but setting the bar even further and saying, technology worldwide, how are we doing against the whole industry? And it’s not to say that the data we can get on that is always perfect, but it helps to set this benchmark and say, how are we doing? Are we good? Are we better than anyone else? Are we behind on certain things?

Karthik Chandrashekar: One thing I see with DORA as a framework is its flexibility. So to the debate that Emily mentioned that they had internally, it’s a very common thing that I see in the community where some organizations essentially look at it as an organizational horizontal view of how the team is doing as a group relative to these benchmarks.

What pitfalls or challenges have you encountered?

Karthik Chandrashekar: From a pure trend perspective, best practice is a framework of “message, measure, and manage.” And not doing that first step of messaging appropriately with the proper context for the organization means that it actually can cause more challenges than not. So a big part of that messaging is psychological safety, bringing the cultural safety of, “this is to your benefit for the teams.” It empowers. The second thing is we all wanna be the best, and here’s our self-empowered way to do that. And then thirdly, I think, “how do we use this to align with the rest of the organization in terms of showcasing the best practices from the engineering org?”

So the challenges would be the inverse of the three things I mentioned. When you don’t measure, people look at it as, “Oh, I’m being measured. I don’t wanna participate in this.” Or when you measure, you go in with a hammer and say, “Oh, this is not good. Go fix it.” Or then you do measure, and everything is great, but then when you are communicating company-wide or even to the board, then it becomes, hey, everything’s rosy, everything is good, but under the hood, it may not necessarily be…Those are some of the challenges I see.

Emily Nakashima: To me, the biggest pitfall was just, you can spend so much time arguing about how to measure these exact things. DORA has described these metrics with words, but how do you map that to what you’re doing in your development process?

For us in particular, we have an hour-timed wait for various reasons because things roll to a staging environment first and get through some automated tests. Our deployment process is an hour. We will wait for 60 minutes plus our test runtime. So we can make incredible progress, making our test faster and making the developer experience better. And we can go from 70 to 65 minutes, which doesn’t sound that impressive but is incredibly meaningful to our team.

And people could get focused on, “Wait, this number doesn’t tell us anything valuable.” And we had to just say, “Hey, this is a baseline. We’re gonna start with it.” We’re gonna just collect this number and look at it for a while and see if it’s meaningful, rather than spend all this time going back and forth on the exact perfect way to measure. It was so much better to just get started and look at it, ’cause I think you learn a lot more by doing than by finding the perfect metric and measuring it the perfect way.

Scott Aucoin: You’re going to have many problems, more than your DevOps practices. And Emily, I think the consistency around how you measure it is something we certainly have struggled with. And I would say in some cases, we still wonder if we’re measuring things the right way, even as we’ve tried to set a standard across our org. I’ll add to that, though, and say the complexity of the technology world, in general, is a significant challenge when you’re trying to introduce something that may feel new or different to the team or just like something else that they need to think about…You have to think about from the standpoint of the priorities of what you’re trying to build, the architecture behind it, security, the ability to just maintain and support your system, your quality, all of the different new technology that we need to consider ways to experiment all of that. And then, and we throw in something else to say, “Okay, make sure you’re looking at this too.” I think just from a time capacity and bandwidth perspective. It can be challenging to get folks to focus and think about, okay, how can we improve on this when we have so many other things we need to think about simultaneously?

What are you doing with DORA metrics now?

Scott Aucoin: It’s a broad spectrum. We’re doing all these fantastic things. Some groups are still not 100% familiar with what it means to look at DORA metrics or how to read them.

It’s kind of a map and compass approach. You’re not only looking at a number; you’re able to see from that number what questions you have and how you can learn from it to map out the direction you want to go. So if you’re lagging behind in Deployment Frequency, maybe you want to think more about smaller batches, for example. So within our teams, we’re looking at it through that lens.

And again, it’s not 100% of the teams. In fact, we still have more promotion and adoption to do around that, but we have the data for the entire organization. So we also look at it from the levels of the global CIO and monthly reports that are monthly operational reports that go to the global CIO. And while I can think about someone who I’ve gotten to know over the last few months, Nathen Harvey, who’s a developer advocate for Google’s DORA team, I have him in the back of my mind as I say this, as he would say, “The metrics are really for the teams.”

We think about the value of it from the executive level as well. And when we think about the throughput metrics of Deployment Frequency and Lead Time for Changes, we can get a little bit muddy when you roll up thousands of applications to this one number for an exact, especially since many of those applications aren’t being worked on regularly. Some are in more of a maintenance mode. But when we can focus on the ones actively being worked on and think about trends, are we improving our Deployment Frequency or not? It can lead the CIO or any of the CIOs in the organization to ask the right questions to think about “what I can do to help this?” Especially when it comes to stability, regardless of whether an application is getting worked on actively today or not, we need stability to be there. So we really are looking at them at multiple levels and trying to be thoughtful about the types of questions that we ask based on the information we’re seeing.

Emily Nakashima: My example is the backward and wrong way to do this. I started by basically just implementing these myself for myself. And the first thing I did with them was to show the stakeholders that I was trying to paint this story too. And I think if you can start with getting practitioners to work with them, getting your software engineers to work with them first, tune them a little bit, and find them relevant, I honestly think that’s the best approach in the organization if you could do it. That wasn’t the situation I happened to be in, but I started with that, used them to radiate these high-level status numbers to other folks on the exec team and the board, and then started to roll them out team by team to allow for that customization.

So we’re still in that process now, but I started to pull managers in one by one and go, hey, these metrics that I’m tracking, this is what they mean to me. Let’s sit down together and figure out what’s gonna be meaningful for your engineering team and how to build on this baseline here…Let’s build on top of it together.

And we’re hoping to get into this quarter to have teams start working with them more directly and get more active in tuning and adding their metrics. We think about observability for systems, and we always want people to be adding instrumentation to their systems as they go. Each time you deploy a feature, add instrumentation that tells you whether or not it’s working. And we wanna bring that same approach to our engineering teams where we have these baseline metrics. If you don’t think they’re that good and they don’t tell you that much, then you go ahead and tell us what metric we add, and we’re gonna work together to build this higher fidelity picture that makes sense to you, and then also have that shared baseline across teams.

To hear more from our panelists, watch the full webinar here.

(Updated: February 26, 2024)

Born from frustration at the silos between development and operations teams, the DevOps philosophy encourages trust, collaboration, and the creation of multidisciplinary teams. As DevOps rose in popularity, DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA) began with the goal of gaining a better understanding of the practices, processes, and capabilities that enable teams to achieve a high velocity and performance when it comes to software delivery. The startup identified four key metrics — the “DORA Metrics” — that engineering teams can use to measure their performance in four critical areas.

This empowers engineering leaders, enabling them to benchmark their teams against the rest of the industry, identify opportunities to improve, and make changes to address them.

What is DORA?

DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA) is a startup created by Gene Kim and Jez Humble with Dr. Nicole Forsgren at the helm. Gene Kim and Jez Humble are best known for their best-selling books, such as The DevOps Handbook. Dr. Nicole Forsgren also joined the pair to co-author Accelerate in 2018.

The company provided assessments and reports on organizations’ DevOps capabilities. They aimed to understand what makes a team successful at delivering high-quality software, quickly. The startup was acquired by Google in 2018, and continues to be the largest research program of its kind. Each year, they survey tens of thousands of professionals, gathering data on key drivers of engineering delivery and performance. Their annual reports include key benchmarks, industry trends, and learnings that can help teams improve.

What are DORA metrics?

DORA metrics are a set of four measurements identified by DORA as the metrics most strongly correlated with success — they’re measurements that DevOps teams can use to gauge their performance. The four metrics are: Deployment Frequency, Mean Lead Time for Changes, Mean Time to Recover, and Change Failure Rate. They were identified by analyzing survey responses from over 31,000 professionals worldwide over a period of six years.

The team at DORA also identified performance benchmarks for each metric, outlining characteristics of Elite, High-Performing, Medium, and Low-Performing teams.

Deployment Frequency

Deployment Frequency (DF) measures the frequency at which code is successfully deployed to a production environment. It is a measure of a team’s average throughput over a period of time, and can be used to benchmark how often an engineering team is shipping value to customers.

Engineering teams generally strive to deploy as quickly and frequently as possible, getting new features into the hands of users to improve customer retention and stay ahead of the competition. More successful DevOps teams deliver smaller deployments more frequently, rather than batching everything up into a larger release that is deployed during a fixed window. High-performing teams deploy at least once a week, while teams at the top of their game — peak performers — deploy multiple times per day.

Low performance on this metric can inform teams that they may need to improve their automated testing and validation of new code. Another area to focus on could be breaking changes down into smaller chunks, and creating smaller pull requests (PRs), or improving overall Deploy Volume.

Mean Lead Time for Changes

Mean Lead Time for Changes (MLTC) helps engineering leaders understand the efficiency of their development process once coding has begun. This metric measures how long it takes for a change to make it to a production environment by looking at the average time between the first commit made in a branch and when that branch is successfully running in production. It quantifies how quickly work will be delivered to customers, with the best teams able to go from commit to production in less than a day. Average teams have an MLTC of around one week.

Deployments can be delayed for a variety of reasons, including batching up related features and ongoing incidents, and it’s important that engineering leaders have an accurate understanding of how long it takes their team to get changes into production.

When trying to improve on this metric, leaders can analyze metrics corresponding to the stages of their development pipeline, like Time to Open, Time to First Review, and Time to Merge, to identify bottlenecks in their processes.

Teams looking to improve on this metric might consider breaking work into smaller chunks to reduce the size of PRs, boosting the efficiency of their code review process, or investing in automated testing and deployment processes.

Change Failure Rate

Change Failure Rate (CFR) is a calculation of the percentage of deployments causing a failure in production, and is found by dividing the number of incidents by the total number of deployments. This gives leaders insight into the quality of code being shipped and by extension, the amount of time the team spends fixing failures. Most DevOps teams can achieve a change failure rate between 0% and 15%.

When changes are being frequently deployed to production environments, bugs are all but inevitable. Sometimes these bugs are minor, but in some cases these can lead to major failures. It’s important to bear in mind that these shouldn’t be used as an occasion to place blame on a single person or team; however, it’s also vital that engineering leaders monitor how often these incidents happen.

This metric is an important counterpoint to the DF and MLTC metrics. Your team may be moving quickly, but you also want to ensure they’re delivering quality code — both stability and throughput are important to successful, high-performing DevOps teams.

To improve in this area, teams can look at reducing the work-in-progress (WIP) in their iterations, boosting the efficacy of their code review processes, or investing in automated testing.

Mean Time to Recovery

Mean Time to Recovery (MTTR) measures the time it takes to restore a system to its usual functionality. For elite teams, this looks like being able to recover in under an hour, whereas for many teams, this is more likely to be under a day.

Failures happen, but the ability to quickly recover from a failure in a production environment is key to the success of DevOps teams. Improving MTTR requires DevOps teams to improve their observability so that failures can be identified and resolved quickly.

Additional actions that can improve this metric are: having an action plan for responders to consult, ensuring the team understands the process for addressing failures, and improving MLTC.

Making the most of DORA metrics

The DORA metrics are a great starting point for understanding the current state of an engineering team, or for assessing changes over time. But DORA metrics only tell part of the story.

To gain deeper insight, it’s valuable to view them alongside non-DORA metrics, like PR Size or Cycle Time. Correlations between certain metrics will help teams identify questions to ask, as well as highlight areas for improvement.

And though the DORA metrics are perhaps the most well-known element of the annual DORA report, the research team does frequently branch out to discuss other factors that influence engineering performance. In the 2023 report, for example, they dive into two additional areas of consideration for top-performing teams: code review and team culture. Looking at these dimensions in tandem with DORA metrics can help leaders enhance their understanding of their team.

It’s also important to note that, as there are no standard calculations for the four DORA metrics, they’re frequently measured differently, even among teams in the same organization. In order to draw accurate conclusions about speed and stability across teams, leaders will need to ensure that definitions and calculations for each metric are standardized throughout their organization.

Why should engineering leaders think about DORA metrics?

Making meaningful improvements to anything requires two elements — goals to work towards and evidence to establish progress. By establishing progress, this evidence can motivate teams to continue to work towards the goals they’ve set. DORA benchmarks give engineering leaders concrete objectives, which then break down further into the metrics that can be used for key results.

DORA metrics also provide insight into team performance. Looking at Change Failure Rate and Mean Time to Recover, leaders can help ensure that their teams are building robust services that experience minimal downtime. Similarly, monitoring Deployment Frequency and Mean Lead Time for Changes gives engineering leaders peace of mind that the team is working quickly. Together, the metrics provide insight into the team’s balance of speed and quality.

Learn more about DORA metrics from the expert himself. Watch our on-demand webinar featuring Nathen Harvey, Developer Advocate at DORA and Google Cloud.

Engineering productivity is notoriously difficult to measure. Classic metrics tend to focus exclusively on outputs, but this approach is flawed — in software engineering, quantity of output isn’t necessarily the most productive goal. Quality is an important complement to quantity, and a team that’s measuring success in lines of code written may sacrifice conciseness for volume. This can lead to bloated, buggy code. A team focused on the number of features shipped may prioritize simple features that they can get out the door quickly, rather than spending time on more complex features that can move the needle for the business. The SPACE Framework aims to address this by replacing output-focused measurements with a more nuanced approach to understanding and optimizing developer productivity.

This research-based framework offers five key dimensions that, viewed in concert, offer a more comprehensive view of a team’s status. These dimensions guide leaders toward measuring and improving factors that impact outputs, rather than focusing solely on the outputs themselves.

Importantly, SPACE foregrounds the developer. It recognizes that leaders must empower their team members with the ability to take ownership of their work, grow their skills, and get things done while contributing to the success of the team as a whole.

What is the SPACE Framework?

The SPACE Framework is a systematic approach to measuring, understanding, and optimizing engineering productivity. Outlined by researchers from Github, Microsoft, and the University of Victoria, it encourages leaders to look at productivity holistically, placing metrics in conversation with each other and linking them to team goals. It breaks engineering productivity into five dimensions, Satisfaction and Well-being; Performance; Activity; Communication and Collaboration; and Efficiency and Flow.

Satisfaction and Well-being – Most often measured by employee surveys, this dimension asks whether team members are fulfilled, happy, and practicing healthy work habits. Satisfaction and well-being are strongly correlated with productivity, and they may even be important leading indicators; unhappy teams that are highly productive are likely headed toward burnout if nothing is done to improve their well-being.

Of all five SPACE dimensions, satisfaction and well-being is the hardest to quantify. Objective metrics can’t directly measure developer happiness, but they can point to circumstances that are likely to cause dissatisfaction or burnout. By viewing quantitative metrics in tandem with qualitative information and survey data, engineering leaders can better assess team satisfaction.

With Code Climate's Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) solution, leaders can view engineering metrics like Coding Balance to get a sense of developer workload. Coding Balance displays the percentage of contributors responsible for 80% of your team’s most impactful work. If work is not evenly distributed, overloaded team members may be overwhelmed, while those doing less impactful work may not be challenged enough.

Another informative measure, Work in Progress PRs, offers a count of Pull Requests with activity over a 72-hour period. A high Work in Progress number could mean that developers are forced to context switch often, which can prevent developers from entering a state of flow. The ideal number of Work in Progress PRs is usually 1-2 PRs per developer.

To get a better understanding of overall satisfaction, engineering leaders should look at both short term changes and overall trends. For example, when an engineering manager at Code Climate noticed a spike in volume of PRs and reviews in a short amount of time, she took it as a sign to further investigate the workload of each developer. When she discovered that engineers were working overtime and on weekends in order to ship new features, she successfully advocated for extra time off to recharge and avoid potential burnout.

Performance – The originators of the SPACE Framework recommend assessing performance based on the outcome of a developer’s work. This could be a measure of code quality, or of the impact their work has on the product’s success.

Metrics that help evaluate performance include Defect Rate and Change Failure Rate. Change Failure Rate is a key performance metric, as it measures the percentage of deployments causing a failure in production, helping engineering leaders understand the quality of the code developed and shipped to customers. Every failure in production takes away time from developing new features and ultimately has a negative impact on customers.

When assessing team performance, PR Throughput is an important counterpoint to quality metrics. This metric counts PRs merged (a bug fix, new feature, or improvement) over time, and is correlated to output and progress. To get a full picture of performance, PR Throughput should be viewed alongside quality metrics; you’ll want to ensure that your team is delivering at volume while maintaining quality.

Activity – This dimension is most reminiscent of older measures of productivity as it refers to developer outputs like on-call participation, pull requests opened, volume of code reviewed, or documents written. Still, the framework reminds leaders that activity should not be viewed in isolation, and it should always be placed in context with qualitative information and other metrics.

Useful Activity metrics to look at include coding metrics, such as Commits Per Day, the average number of times Active Contributors commit code per coding day, and Pushes Per Day, the average number of times Active Contributors are pushing per day.

These metrics offer an overview of developer activity so you can gauge whether or not work is balanced, if workload matches expectations, and whether delivery capacity is in line with strategic goals.

It can also be helpful to look at Deployment Frequency, which measures how often teams deliver new features or bug fixes to production.

Communication and Collaboration – The most effective teams have a high degree of transparency and communication. This helps ensure developers are aligned on priorities, understand how their work fits into broader initiatives, and can learn from each other. Proxies for measuring communication and collaboration might include review coverage or documentation quality.

Code Climate supports Pair Programming, which encourages collaboration. Credit can be attributed to two developers who write code in a pairing session.

Metrics like Review Speed, Time to first Review, and Review Coverage, can help you assess the health of your collaborative code review process. These metrics can help identify whether your team is keeping collaboration top of mind, has enough time to review PRs, and is giving thoughtful feedback in comments.

Efficiency and Flow – In the SPACE framework, flow refers to a state of individual efficiency where work can be completed quickly, with limited interruption. Efficiency is similar, but it occurs at the team level. Both are important for minimizing developer frustration. (Though it’s worth noting that when an organization has too much efficiency and flow, it’s not always a good thing, as it may be at the expense of collaboration or review.) Perceived efficiency and flow can be important information gathered via survey, while speed metrics can capture a more objective measurement.

In Code Climate's SEI platform, Cycle Time is an important metric to view within the context of efficiency and flow, as well as Mean Lead Time for Changes. Cycle Time, aka your speedometer, is representative of your team’s time to market. A low Cycle Time often means a higher output of new features and bug fixes being delivered to your customers. Cycle Time is an objective way to evaluate how process changes are affecting your team’s output. Often, a high output with quality code can speak to a team’s stability.

Mean Lead Time for Changes, which refers to DevOps speed, measures how quickly a change in code makes it through to production successfully. This can be correlated to team health and ability to react quickly. Like Cycle Time, it can indicate whether your team’s culture and processes are effective in handling a large volume of requests.

How can you implement the SPACE Framework?

The framework’s authors caution that looking at all five dimensions at once is likely to be counterproductive. They recommend choosing three areas that align with team priorities and company goals. What a team chooses to measure will send a strong signal about what the team values, and it’s important to be deliberate about that decision. They also remind leaders to be mindful of invisible work and to check for biases in their evaluations.

At Code Climate, we’ve spent years helping software engineering leaders leverage engineering data to boost their teams’ productivity, efficiency, and alignment. With that experience in mind, we have a few additional recommendations:

- Be transparent. When introducing data in your organization or using data in a new way, it’s important to be open. Make sure your team members know what data you’re looking at, how you plan to use it, and what value you hope to gain from it.

- Place all metrics in context. Quantitative data can only tell you so much. It’s critical to supplement metrics with qualitative information, or you’ll miss key insights. For example, if you’re measuring activity metrics and see a decrease in pull requests opened, it’s important to talk to your team members about why that’s happening. You may find out that they’ve been spending more time in meetings, so they can’t find time to code. Or you may learn that they’re coding less because they’re working to make sense of the technical direction. Both these situations may impact activity, but will need to be addressed in very different ways.

- Work data into your existing processes. The most effective way to build a new habit is to layer it onto an existing one. If you’re already holding regular 1:1s, standups, and retros, you can use them as an opportunity to present data to your team, assess progress toward goals, and discuss opportunities for improvement. By bringing data to your meetings, you can help keep conversations on track and grounded in facts.

Why does the SPACE Framework matter?

The SPACE Framework helps engineering leaders think holistically about developer productivity. The five dimensions serve as critical reminders that developer productivity is about more than the work of one individual, but about the way a team comes together to achieve a goal. And perhaps somewhat counterintuitively, understanding productivity is about more than simply measuring outputs. In looking at multiple dimensions, teams can gain a fuller understanding of the factors influencing their productivity, and set themselves up for sustainable, long-term success.

Learn how you can use data to enhance engineering performance and software delivery by requesting a consultation.

Technology leaders looking to drive high performance can support the evolution of their teams by creating a culture of feedback in their organization. Read on to find out why honest and constructive feedback is crucial to engineering success.

The Importance of Routine Feedback

Regular feedback on particular units of work, processes, and best practices can be an effective way to help ensure agile teams are aligned and that all requirements are understood and met.

Employees who receive regular feedback on their work feel more confident and secure in their positions because they understand what is expected of them and the role they play in the organizational structure. According to one report, only 43% of highly-engaged employees received feedback on a weekly basis, while an astonishing 98% said they fail to be engaged when managers give little to no feedback, showcasing how essential feedback is to the cohesiveness of teams.

Furthermore, a positive culture of feedback can enhance psychological safety on teams. When feedback is a fundamental part of a blameless team culture, team members understand that feedback is critical to growing as a team and achieving key goals, and will likely feel more secure in sharing ideas, acknowledging weaknesses, and asking for help.

How to Foster a Feedback-rich Culture

As an executive, it is important to lead by example, as your actions can serve as a benchmark for best practices to be followed throughout the organization.

Leverage the Power of 1:1’s

Regular check-ins can play an integral role in building a successful feedback culture. Providing dedicated time for managers and direct reports to discuss goals, share feedback, and more, 1:1’s are a great way to engage employees and build trust.

During your 1:1’s, you’ll have the opportunity to ask questions and make statements that:

- Build an interpersonal connection – “How are you and your family”

- Encourage collaboration – “What’s on your mind? Is there anything I can help you with that you may be stuck on?”

- Show recognition, appreciation, or provide coaching

Here at Code Climate, our executives and managers hold weekly 1:1’s with their direct reports to surface any process blockers, discuss ambitions, and generally catch up. We are committed to this practice as a way to foster safety, transparency, and cohesion within our organization. We aim to ensure that each team member understands how their work fits into larger company initiatives and feels secure enough to share ideas that enable us to continually innovate and improve.

Enhance Feedback with Engineering Data

The most effective feedback is specific and actionable, so it can be helpful to use engineering data to ground conversations in particular units of work. For example, if you have a question on a specific Pull Request, it can be helpful to surface detailed information on that particular PR to help you place progress in context and check any assumptions you may have. Objective data can also help you identify areas where coaching may be beneficial or showcase areas where you might not have known an IC was excelling. Furthermore, data can help you set and track progress towards goals, adding value and effectiveness to your feedback.

Feedback Goes Both Ways

A culture of feedback is most effective when it’s holistic, so it’s important to make sure you’re giving your team members the opportunity to impart their feedback on processes, workflow, expectations, and more. To help achieve this, you can provide your team members with a forum to share viewpoints during 1:1’s, standups, and retrospectives. In doing so, you regularly afford yourself the opportunity to actively listen to and learn from your team.

Feedback is an essential tool that helps leaders drive excellence on their teams. Remember:

- A culture of positive feedback helps create the ideal conditions for innovation

- 1:1’s can be a powerful way to build trust and create alignment

- Engineering data can help you place observations in context

- A true culture of feedback requires that team members are also empowered to speak up and offer their feedback

With a thoughtful approach, you can cultivate a safe and welcoming work environment that motivates teams to strive for excellence. To find out how to employ data-driven feedback in your organization, request a consultation.

We’re introducing a new look for our Velocity navigation! The platform is growing, and we’ve redesigned the navigation to make it even easier to use Velocity to find the answers you’re looking for.

Things look a bit different, but don’t worry, all your favorite reports are still there (plus more!) — they’re just organized in a new way, around what you’re trying to use Velocity for.

Velocity’s all-new navigation now lives at the top of the page, organized into the following three categories:

Align — Create transparency that ensures your technical teams are in sync with product and business initiatives. Here you can find reports aimed at helping executives align on business priorities and ensure optimal resource allocation across teams.

You’ll be able to understand how your team’s productivity changes over time and visualize key metrics to uncover trends.

Deliver — Innovate faster than your competition by bringing new products and features to market, faster. These reports are designed to help engineering leadership deliver high-quality code quickly and consistently.

You can easily see what your team is working on (such as what pull requests have been recently edited) and understand how Code Review and PR Resolution are impacting your team’s delivery time.

Improve — Build a culture of excellence through objective metrics. Here you can find reports designed to help leadership and team managers improve team processes and skills to create a high-performance culture.

You can track how your team is progressing towards their goals and performing over time to help identify the best practices that make sense in your organization.

This is a fresh take on the same insightful Velocity reports you’ve been using. We’ll be rolling this out to all of our users by the end of January. Please reach out to support if you have any questions!

Velocity Navigation is Just the Latest in a String of New Product Features for 2022

The new Velocity navigation is the latest of several new product features. We kicked off 2022 with three other highly-requested features: pair programming support, draft PR support, and updated email and Slack PR links. Read more about these new features in our blog announcement, or here’s a quick summary:

Pair Programming – Those engineering teams, including ours, that use pair programming sessions to help increase efficiency, minimize errors, and engender a culture of collaboration and knowledge-sharing on their teams, can now find co-authorship data included in key metrics and reports.

Draft PRs – Draft PR support allows developers to push their work without unintentionally signaling to a manager that the PR is ready to be formally reviewed and/or shipped. Organizations can now customize when Velocity considers a PR to be Ready for Review.

PR Links – The PR links in Velocity’s e-mail and Slack alerts now route directly to your VCS, rather than Velocity (as they did before). This way, any user with access to the PR — even those without a Velocity seat — can act on e-mail and Slack alerts.

We’ve got a ton of new and exciting features on tap for 2022. Stay tuned for more updates that help maximize the data-driven insights you get from Velocity’s Engineering Intelligence.

This is the second post in a two-part series. Read the first post here.

When you use an Engineering Intelligence Solution to answer the classic three standup questions, you free up your team’s valuable meeting time for an even more impactful set of conversations. You’ll be able to spend less time gathering information and more time leveraging your expertise as a leader — once you’re no longer using facetime to surface issues, you can actually start solving them.

To frame these conversations, I recommend a new set of questions to ask in standup meetings:

- How can I help remove distractions?

- How can the team help reduce risk?

- Are we working on the right things?

Here’s how to get the most out of each one.

Question 1 to ask in standup meetings: How can I help remove distractions?

To most effectively answer this question, you’ll need to come to standup prepared. Take a look through your Engineering Intelligence Solution and keep an eye out for patterns that might indicate your team’s attention is fragmented, such as engineers who are making commits on multiple different Issues, or team members who have stopped committing for a few days. Code Climate's Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) solution offers visualizations of individual developers’ coding activity, which makes these patterns particularly easy to spot.

If you notice an engineer bouncing around, committing to multiple pieces of work in a short time period, it’s possible that engineer is trying to do too much at once. Have a conversion with that developer, and find out exactly what’s causing them to work in this way. It’s possible that they’re trying to make progress on multiple fronts at the same time, or that they’re being pulled in different directions by external forces, bouncing from project to project whenever a stakeholder asks a question or requests a status update. As their manager, you’re in a position to help the engineer develop the tools they need to devote the necessary level of focus to each unit of work. Exactly how you help depends on the situation — a more junior engineer may benefit from some coaching in project management skills, while a more senior engineer may need assistance contextualizing and prioritizing their work.

Of course, every engineer is juggling multiple things at once, and it’s not uncommon for someone to jump to a new project while they’re waiting for a Pull Request (PR) to be reviewed. Still, there’s a point at which task switching becomes excessive, and the visualizations in an SEI platform make that really clear, revealing potentially problematic switching in a haphazard assortment of commits, or delays getting back to paused units of work.

Sometimes, the delay itself is noteworthy. If an engineer is committing to something every day, then stops for a significant period of time before picking it back up again, it’s likely they’ve been pulled away to work on something else. Given how much time engineering teams spend grooming and prioritizing their backlog, this sort of deviation from the plan can be problematic, and yet, well-meaning developers often say yes to side tasks and additional projects without thinking about the cost. As a leader, if you notice this occurring, you can help your team members determine whether unplanned work is worthy of urgent attention, and remind them to assess any new tasks with you before taking them on.

Question 2 to ask in standup meetings: How can the team help reduce risk?

This question gets to one of the key goals of standup meetings: spotting and resolving problems before they derail sprints. Work that is at-risk is work that has started to go off track but hasn’t gone completely off the rails yet, which means you have the opportunity to stay a step ahead of a real problem. An SEI platform will alert you whenever a unit of work meets your criteria for “at-risk,” whether it’s a PR that has stalled without review or one that has too many contributing engineers, giving you the opportunity to quickly get the work back on track.

While some at-risk work can be indicative of larger issues — outdated processes or recurring bottlenecks in your development pipeline — at-risk work is often the result of a miscommunication regarding who should be doing what. For example, it’s common to see work get stuck in work in Code Review because everyone thought it was being reviewed by someone else on the team. When you bring risky units of work to standup for discussion, your team can quickly implement any straightforward fixes, then set aside time to work through bigger issues.

Question 3 to ask in standup meetings: Are we working on the right things?

With an SEI solution, you can easily see what units of work are progressing, so you can ensure your team members are working on the right things. Let’s say you prioritized tickets coming into your sprint, but notice that a developer is committing against the lowest priority Issue — you can discuss this as a team and rebuild alignment in the moment, rather than pretending you’ll always get it right at the top of the sprint. Almost certainly there was a miscommunication, and the developer jumped on what they thought was an important unit of work, though it’s also possible that an engineer thought the low-priority item was easiest to tackle and wanted to get it out of the way. This is rarely a good reason not to work on the highest priority things, and you can help coach the developer back to more important units of work. In some cases, the low-priority item may be the only thing the developer understood, so they jumped into it despite its low importance. This is important to know and address because if one person on the team doesn’t understand something, chances are other members of the team are also confused.

Whatever caused the low-priority item to be started, the team now has the opportunity to decide what to do about the unit of work in question. It may be that the work is so far along it makes sense to finish it, or it may be something the team decides to pause until higher-priority work is completed. Without a SEI solution, there would be no choice to make, as you’d only find out that someone was working on the ‘wrong’ thing after the work was already complete.

Data is a Powerful Tool for Skilled Managers

Though some leaders hesitate to leverage data, fearing that it breeds micromanagement, it’s important to remember that you’re already gathering information about stalled work or stuck engineers. Standups are one of the many ways managers seek out that information, but they’re not the most efficient way, since meeting time is better used for solving problems than surfacing them.

True micromanagement is not found in the gathering of data, but in how that data is used; micromanagers wield punishments and prescribe solutions, while great managers ask questions, offer guidance, and help their teams collaborate on solutions. With a Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) solution pointing you towards work that needs attention, you’ll spend less time looking for opportunities to help and more time actually managing your team.