Our latest post comes from Giles Bowkett. Giles recently wrote a book, Rails As She Is Spoke, which explores Rails’ take on OOP and its implications. It’s an informative and entertaining read, and you should buy it.

A few days ago I wrote a blog post arguing that rails developers should take DCI seriously. Be careful what you wish for! A tumultuous brouhaha soon ensued on Twitter. I can’t necessarily take the credit for that, but I’m glad it happened, because one of the people at the center of the cyclone, Rails creator David Heinemeier Hansson, wrote a good blog post on ActiveSupport::Concern, which included a moment of taking DCI seriously.

[…] breaking up domain logic into concerns is similar in some ways to the DCI notion of Roles. It doesn’t have the run-time mixin acrobatics nor does it have the “thy models shall be completely devoid of logic themselves” prescription, but other than that, it’ll often result in similar logic extracted using similar names.

DCI (data, context, and interaction) is a paradigm for structuring object-oriented code. Its inventor, Trygve Reenskaug, also created MVC, an object-oriented paradigm every Rails developer should be familiar with. Most Rubyi mplementations use mixins quite a lot, and there is indeed some similarity there.

However, there’s a lot more to DCI than just mixins, and since I’ve already gone into detail about it elsewhere, as have many others, I won’t get into that here. I’m very much looking forward to case studies from people who’ve used it seriously. Likewise, there are a lot of good reasons to feel cautious about using mixins, either for Rails concerns or for DCI, but that discussion’s ongoing and deserves (and is receiving) several blog posts of its own.

What I want to talk about is this argument in Hansson’s blog post:

I find that concerns are often just the right amount of abstraction and that they often result in a friendlier API. I far prefer current_account.posts.visible_to(current_user) to involving a third query object. And of course things like Taggable that needs to add associations to the target object are hard to do in any other way. It’s true that this will lead to a proliferation of methods on some objects, but that has never bothered me. I care about how I interact with my code base through the source.

I added the emphasis to the final sentence because I think it’s far more important than most people realize.

To explain, I want to draw an example from my new book Rails As She Is Spoke, which has a silly title but a serious theme, namely the ways in which Rails departs from traditional OOP, and what we can learn from that. The example concerns the familiar method url_for. But I should say “methods,” because the Rails code base (as of version 3.2) contains five different methods named url_for.

The implementations for most of these methods are hideous, and they make it impossible not to notice the absence of a Url class anywhere in the Rails code base — a truly bizarre bit of domain logic for a Web framework not to model — yet these same, hideously constructed methods enable application developers to use a very elegant API:

url_for controller: foo, action: bar, additional: whatnot

Consider again what Hansson said about readable code:

I care about how I interact with my code base through the source.

I may be reading too much into a single sentence here, but after years of Rails development, I strongly believe that Rails uses this statement about priorities as an overarching design principle. How else do you explain a Web framework that does not contain a Url class within its own internal domain logic, yet provides incredible conveniences like automated migrations and generators for nearly every type of file you might need to create?

The extraordinary internal implementation of ActiveRecord::Base, and its extremely numerous modules, bends over backwards to mask all the complexity inherent in instantiating database-mapping objects. It does much, much less work to make its own internal operations easy to understand, or easy to reason about, or easy to subclass, and if you want to cherry-pick functionality from ActiveRecord::Base, your options span a baffling range from effortless to impossible.

Consider a brief quote from this recent blog post on the params object in Rails controllers:

In Ruby, everything is an object and this unembarrassed object-orientation gives Ruby much of its power and expressiveness. […] In Rails, however, sadly, there are large swathes which are not object oriented, and in my opinion, these areas tend to be the most painful parts of Rails.

I agree with part of this statement. I think it’s fair to say that Ruby takes its object-oriented nature much more seriously than Rails does. I also agree that customizing Rails can be agonizingly painful, whenever you dip below the framework’s beautifully polished surface into the deeper realms of its code, which is sometimes object-oriented and sometimes not. But if you look at this API:

url_for controller: foo, action: bar, additional: whatnot

It doesn’t look like object-oriented code at all. An object-oriented version would look more like this:

Url.new(:foo, :bar, additional: whatnot)

The API Rails uses looks like Lisp, minus all the aggravating parentheses.

(url_for ((controller, 'foo), (action, 'bar), (additional, whatnot)))

That API is absolutely not, in my opinion, one of “the most painful parts of Rails.” It’s one of the least painful parts of Rails. I argue in my book that Rails owes a lot of its success to creating a wonderful user experience for developers — making it the open source equivalent of Apple — and I think this code is a good example.

Rails disregards object orientation whenever being object-oriented stands in the way of a clean API, and I actually think this is a very good design decision, with one enormous caveat: when Rails first debuted, Rails took a very firm position that it was an opinionated framework very highly optimized for one (and only one) particular class of Web application.

If (and only if) every Rails application hews to the same limited range of use cases, and never strays from the same narrow path of limited complexity, then (and onlythen) it makes perfect sense to prioritize the APIs which developers see over their ability to reason about the domain logic of their applications and of the framework itself.

Unfortunately, the conditions of my caveat do not pertain to the overwhelming majority of Rails apps. This is why Rails 3 abandoned the hard line on opinionated software for a more conciliatory approach, which is to say that Rails is very highly optimized for a particular class of Web application, but sufficiently modular to support other types of Web applications as well.

If you take this as a statement about the characteristics of Rails 3, it’s outrageously false, but if you take it as a design goal for Rails 3 and indeed (hopefully) Rails 4, it makes a lot of sense and is a damn good idea.

In this context, finding “just the right amount of abstraction” requires more than just defining the most readable possible API. It also requires balancing the most readable possible API with the most comprehensible possible domain model. There’s an analogy to human writing: you can’t just write beautiful sentences and call it a day. If you put beautiful sentences on pages at random, you might have poetry, if you get lucky, but you won’t have a story.

This is an area where DCI demolishes concerns, because DCI provides an entire vocabulary for systematic decomposition. If there’s any guiding principle for decomposing models with concerns, I certainly don’t recall seeing it, ever, even once, in my 7 years as a Rails developer. As far as I can tell the closest thing is: “Break the class into multiple files if…”

- There are too many lines of code.

- It’s Tuesday.

- It’s not Tuesday.

DCI gives developers something more fine-grained.

I’m not actually a DCI zealot; I’m waiting until I’ve built an app with DCI and had it running for a while before I make any strident or definitive statements. The Code Climate blog itself featured some alternative solutions to the overburdened models problem, and these solutions emphasize classes over mixins. You could do worse than to follow them to the letter. Other worthwhile alternatives exist as well; there is no silver bullet.

However, Rails concerns are just one way to decompose overburdened models. Concerns are appropriate for some apps and inappropriate for others, and I suspect the same is true of DCI. Either way, if you want to support multiple types of applications, with multiple levels and types of complexity, then making a blanket decision about “just the right amount of abstraction” is pretty risky, because that decision may in fact function at the wrong level of abstraction itself.

It doesn’t take a great deal of imagination to understand that different apps feature different levels of complexity, and you should choose which technique you use for managing complexity based on how much complexity you’re going to be managing. As William Gibson said, “the street finds its own uses for things,” and I think most Rails developers use Rails to build apps that are more complex than the apps Rails is optimized for. I’ve certainly seen apps where that was true, and in those apps, concerns did not solve the problem.

It’s possible this means people should be using Merb instead of Rails, although that train appears to have left the station (and of course it left the station on Rails).

Related Articles

Navigating the world of software engineering or developer productivity insights can feel like trying to solve a complex puzzle, especially for large-scale organizations. It's one of those areas where having a cohesive strategy can make all the difference between success and frustration. Over the years, as I’ve worked with enterprise-level organizations, I’ve seen countless instances where a lack of strategy caused initiatives to fail or fizzle out.

In my latest webinar, I breakdown the key components engineering leaders need to consider when building an insights strategy.

Why a Strategy Matters

At the heart of every successful software engineering team is a drive for three things:

- A culture of continuous improvement

- The ability to move from idea to impact quickly, frequently, and with confidence

- A software organization delivering meaningful value

These goals sound simple enough, but in reality, achieving them requires more than just wishing for better performance. It takes data, action, and, most importantly, a cultural shift. And here's the catch: those three things don't come together by accident.

In my experience, whenever a large-scale change fails, there's one common denominator: a lack of a cohesive strategy. Every time I’ve witnessed a failed attempt at implementing new technology or making a big shift, the missing piece was always that strategic foundation. Without a clear, aligned strategy, you're not just wasting resources—you’re creating frustration across the entire organization.

Sign up for a free, expert-led insights strategy workshop for your enterprise org.

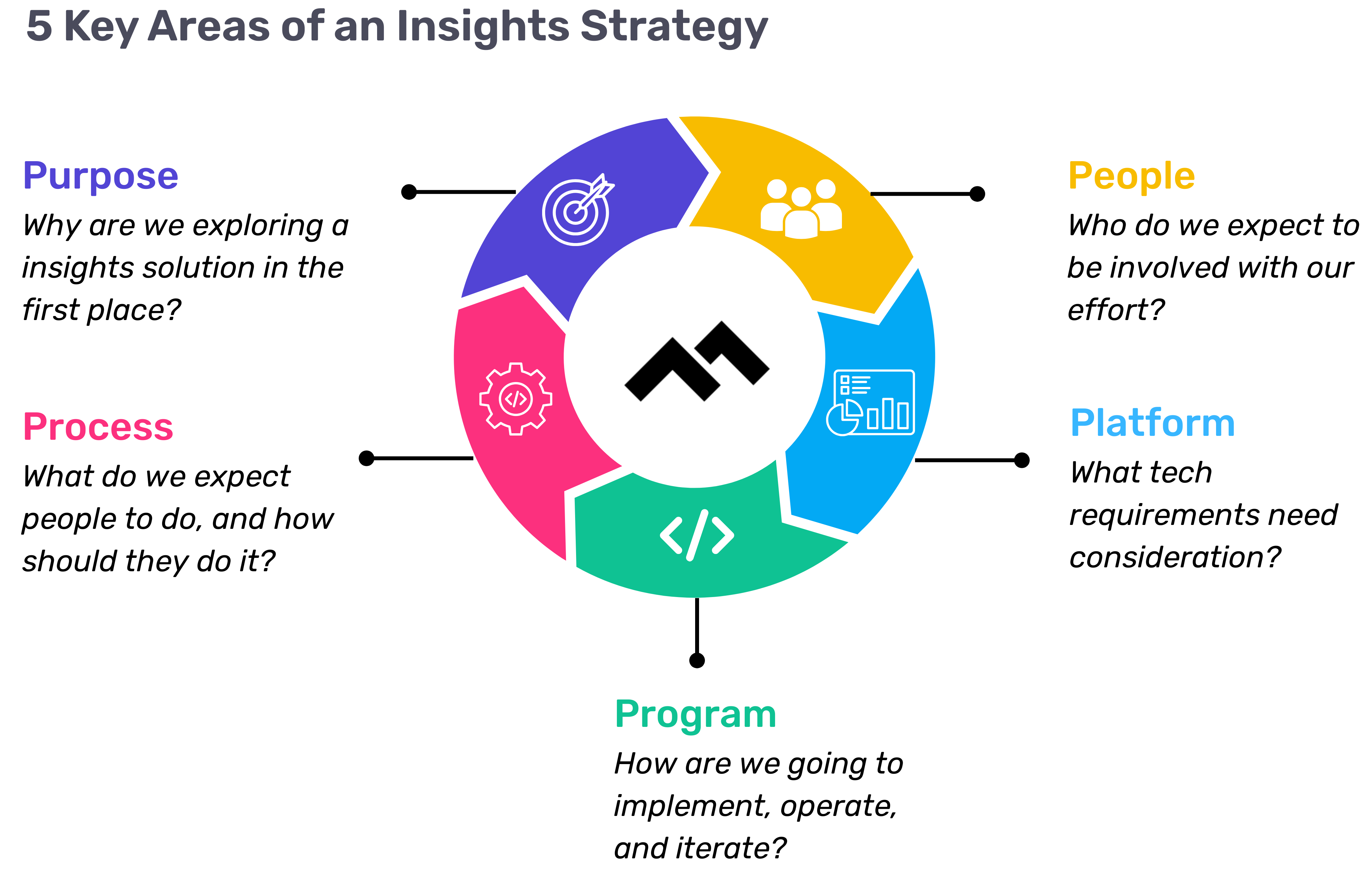

Step 1: Define Your Purpose

The first step in any successful engineering insights strategy is defining why you're doing this in the first place. If you're rolling out developer productivity metrics or an insights platform, you need to make sure there’s alignment on the purpose across the board.

Too often, organizations dive into this journey without answering the crucial question: Why do we need this data? If you ask five different leaders in your organization, are you going to get five answers, or will they all point to the same objective? If you can’t answer this clearly, you risk chasing a vague, unhelpful path.

One way I recommend approaching this is through the "Five Whys" technique. Ask why you're doing this, and then keep asking "why" until you get to the core of the problem. For example, if your initial answer is, “We need engineering metrics,” ask why. The next answer might be, “Because we're missing deliverables.” Keep going until you identify the true purpose behind the initiative. Understanding that purpose helps avoid unnecessary distractions and lets you focus on solving the real issue.

Step 2: Understand Your People

Once the purpose is clear, the next step is to think about who will be involved in this journey. You have to consider the following:

- Who will be using the developer productivity tool/insights platform?

- Are these hands-on developers or executives looking for high-level insights?

- Who else in the organization might need access to the data, like finance or operations teams?

It’s also crucial to account for organizational changes. Reorgs are common in the enterprise world, and as your organization evolves, so too must your insights platform. If the people responsible for the platform’s maintenance change, who will ensure the data remains relevant to the new structure? Too often, teams stop using insights platforms because the data no longer reflects the current state of the organization. You need to have the right people in place to ensure continuous alignment and relevance.

Step 3: Define Your Process

The next key component is process—a step that many organizations overlook. It's easy to say, "We have the data now," but then what happens? What do you expect people to do with the data once it’s available? And how do you track if those actions are leading to improvement?

A common mistake I see is organizations focusing on metrics without a clear action plan. Instead of just looking at a metric like PR cycle times, the goal should be to first identify the problem you're trying to solve. If the problem is poor code quality, then improving the review cycle times might help, but only because it’s part of a larger process of improving quality, not just for the sake of improving the metric.

It’s also essential to approach this with an experimentation mindset. For example, start by identifying an area for improvement, make a hypothesis about how to improve it, then test it and use engineering insights data to see if your hypothesis is correct. Starting with a metric and trying to manipulate it is a quick way to lose sight of your larger purpose.

Step 4: Program and Rollout Strategy

The next piece of the puzzle is your program and rollout strategy. It’s easy to roll out an engineering insights platform and expect people to just log in and start using it, but that’s not enough. You need to think about how you'll introduce this new tool to the various stakeholders across different teams and business units.

The key here is to design a value loop within a smaller team or department first. Get a team to go through the full cycle of seeing the insights, taking action, and then quantifying the impact of that action. Once you've done this on a smaller scale, you can share success stories and roll it out more broadly across the organization. It’s not about whether people are logging into the platform—it’s about whether they’re driving meaningful change based on the insights.

Step 5: Choose Your Platform Wisely

And finally, we come to the platform itself. It’s the shiny object that many organizations focus on first, but as I’ve said before, it’s the last piece of the puzzle, not the first. Engineering insights platforms like Code Climate are powerful tools, but they can’t solve the problem of a poorly defined strategy.

I’ve seen organizations spend months evaluating these platforms, only to realize they didn't even know what they needed. One company in the telecom industry realized that no available platform suited their needs, so they chose to build their own. The key takeaway here is that your platform should align with your strategy—not the other way around. You should understand your purpose, people, and process before you even begin evaluating platforms.

Looking Ahead

To build a successful engineering insights strategy, you need to go beyond just installing a tool. An insights platform can only work if it’s supported by a clear purpose, the right people, a well-defined process, and a program that rolls it out effectively. The combination of these elements will ensure that your insights platform isn’t just a dashboard—it becomes a powerful driver of change and improvement in your organization.

Remember, a successful software engineering insights strategy isn’t just about the tool. It’s about building a culture of data-driven decision-making, fostering continuous improvement, and aligning all your teams toward achieving business outcomes. When you get that right, the value of engineering insights becomes clear.

Want to build a tailored engineering insights strategy for your enterprise organization? Get expert recommendations at our free insights strategy workshop. Register here.

Andrew Gassen has guided Fortune 500 companies and large government agencies through complex digital transformations. He specializes in embedding data-driven, experiment-led approaches within enterprise environments, helping organizations build a culture of continuous improvement and thrive in a rapidly evolving world.

Most organizations are great at communicating product releases—but rarely do the same for process improvements that enable those releases. This is a missed opportunity for any leader wanting to expand “growth mindset,” as curiosity and innovation is as critical for process improvement as it is product development.

Curiosity and innovation aren’t limited to product development. They’re just as essential in how your teams deliver that product. When engineering and delivery leaders share what they’re doing to find efficiencies and unclog bottlenecks, they not only improve Time to Value — they help their peers level up too.

Create Buzz Around Process Wins

Below is a template leaders can use via email or communication app (Slack, Microsoft Teams) to share process changes with their team. I’ve personally seen updates like this generate the same level of energy as product announcements—complete with clap emojis👏 and follow-up pings like “Tell me more!” Even better, they’re useful for performance reviews and make great resume material for the leads who author them (excluding any sensitive or proprietary content, of course).

Subject: [Experiment update]

[Date]

Experiment Lead: [Name]

Goal: [Enter the longer term goal your experiment was in service of]

Opportunity: [Describe a bottleneck or opportunity you identified for some focused improvement]

Problem: [Describe the specific problem you aimed to solve]

Solution: [Describe the very specific solution you tested]

Metric(s): [What was the one metric you determined would help you know if your solution solved the problem? Were there any additional metrics you kept track of, to understand how they changed as well?]

Action: [Describe, in brief, what you did to get the result]

Result: [What was the result of the experiment, in terms of the above metrics?]

Next Step: [What will you do now? Will you run another experiment like this, design a new one, or will you rollout the solution more broadly?]

Key Learnings: [What did you learn during this experiment that is going to make your next action stronger?]

Please reach out to [experiment lead’s name] for more detail.

Sample Use Case

Subject: PR Descriptions Boost Review Speed by 30%

March 31, 2025

Experiment Lead: Mary O’Clary

Goal: We must pull a major capability from Q4 2024 into Q2 2025 to increase our revenue. We believe we can do this by improving productivity by 30%.

Opportunity: We found lack of clear descriptions were a primary cause of churn & delay during the review cycle. How might we improve PR descriptions, with information reviewers need?

Problem: Help PR Reviewers more regularly understand the scope of PRs, so they don’t need to ask developers a bunch of questions.

Solution: Issue simple guidelines for what we are looking for PR descriptions

Metric(s): PR Review Speed. We also monitored overall PR Cycle Time, assuming it would also improve for PRs closed within our experiment timeframe.

Action: We ran this experiment over one 2 week sprint, with no substantial changes in complexity of work or composition of the team. We kept the timeframe tight to help eliminate additional variables.

Result: We saw PR Review Speed increase by 30%

Next Step: Because of such a great result and low perceived risk, we will roll this out across Engineering and continue to monitor both PR Review Speed & PR Cycle Time.

Key Learnings: Clear, consistent PR descriptions reduce reviewer friction without adding developer overhead, giving us confidence to expand this practice org-wide to help accelerate key Q2 2025 delivery.

Please reach out to Mary for more detail.

How Make This Process Stick

My recommendation is to appoint one “editor in chief” to issue these updates each week. They should CC the experiment lead on the communication to provide visibility. In the first 4-6 weeks, this editor may need to actively solicit reports and coach people on what to share. This is normal—you’re building a new behavior. During that time, it's critical that managers respond to these updates with kudos and support, and they may need to be prompted to do so in the first couple of weeks.

If these updates become a regular ritual, within ~3 months, you’ll likely have more contributions than you can keep up with. That’s when the real cultural shift happens: people start sharing without prompting, and process improvement becomes part of how your org operates.

I’ve seen this work in large-scale organizations, from manufacturing to healthcare. Whether your continuous improvement culture is just getting started or already mature, this small practice can help you sustain momentum and deepen your culture of learning.

Give it a shot, and don’t forget to celebrate the wins along the way.

Jen Handler is the Head of Professional Services at Code Climate. She’s an experienced technology leader with 20 years of building teams that deliver outcome-driven products for Fortune 50 companies across industries including healthcare, hospitality, retail, and finance. Her specialties include goal development, lean experimentation, and behavior change.

Output is not the same as impact. Flow is not the same as effectiveness. Most of us would agree with these statements—so why does the software industry default to output and flow metrics when measuring success? It’s a complex issue with multiple factors, but the elephant in the room is this: mapping engineering insights to meaningful business impact is far more challenging than measuring developer output or workflow efficiency.

Ideally, data should inform decisions. The problem arises when the wrong data is used to diagnose a problem that isn’t the real issue. Using misaligned metrics leads to misguided decisions, and unfortunately, we see this happen across engineering organizations of all sizes. While many companies have adopted Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) platforms—whether through homegrown solutions or by partnering with company that specializes in SEI like Code Climate—a clear divide has emerged. Successful and mature organizations leverage engineering insights to drive real improvements, while others collect data without extracting real value—or worse, make decisions aimed solely at improving a metric rather than solving a real business challenge.

From our experience partnering with large enterprises with complex structures and over 1,000 engineers, we’ve identified three key factors that set high-performing engineering organizations apart.

1. Treating Software Engineering Insights as a Product

When platform engineering first emerged, early innovators adopted the mantra of “platform as a product” to emphasize the key principles that drive successful platform teams. The same mindset applies to Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI). Enterprise organizations succeed when they treat engineering insights as a product rather than just a reporting tool.

Data shouldn’t be collected for the sake of having it—it should serve a clear purpose: helping specific users achieve specific outcomes. Whether for engineering leadership, product teams, or executive stakeholders, high-performing organizations ensure that engineering insights are:

- Relevant – Focused on what each audience actually needs to know.

- Actionable – Providing clear next steps, not just numbers.

- Timely – Delivered at the right moment to drive decisions.

Rather than relying on pre-built dashboards with generic engineering metrics, mature organizations customize reporting to align with team priorities and business objectives.

For example, one of our healthcare customers is evaluating how AI coding tools like GitHub Copilot and Cursor might impact their hiring plans for the year. They have specific questions to answer and are running highly tailored experiments, making a custom dashboard essential for generating meaningful, relevant insights. With many SEI solutions, they would have to externalize data into another system or piece together information from multiple pages, increasing overhead and slowing down decision-making.

High-performing enterprise organizations don’t treat their SEI solution as static. Team structures evolve, business priorities shift, and engineering workflows change. Instead of relying on one-size-fits-all reporting, they continuously refine their insights to keep them aligned with business and engineering goals. Frequent iteration isn’t a flaw—it’s a necessary feature, and the best organizations design their SEI operations with this in mind.

2. The Value of Code is Not the Code

Many software engineering organizations focus primarily on code-related metrics, but writing code is just one small piece of the larger business value stream—and rarely the area with the greatest opportunities for improvement. Optimizing code creation can create a false sense of progress at best and, at worst, introduce unintended bottlenecks that negatively impact the broader system.

High-performing engineering organizations recognize this risk and instead measure the effectiveness of the entire system when evaluating the impact of changes and decisions. Instead of focusing solely on PR cycle time or commit activity, top-performing teams assess the entire journey:

- Idea generation – How long does it take to move from concept to development?

- Development process – Are teams working efficiently? Are bottlenecks slowing down releases?

- Deployment & adoption – Once shipped, how quickly is the feature adopted by users?

- Business outcomes – Did the feature drive revenue, retention, or efficiency improvements?

For example, reducing code review time by a few hours may seem like an efficiency win, but if completed code sits for six weeks before deployment, that improvement has little real impact. While this may sound intuitive, in practice, it’s far more complicated—especially in matrixed or hierarchical organizations, where different teams own different parts of the system. In these environments, it’s often difficult, though not impossible, for one group to influence or improve a process owned by another.

One of our customers, a major media brand, had excellent coding metrics yet still struggled to meet sprint goals. While they were delivering work at the expected rate and prioritizing the right items, the perception of “failed sprints” persisted, creating tension for engineering leadership. After further analysis, we uncovered a critical misalignment: work was being added to team backlogs after sprints had already started, without removing any of the previously committed tasks. This shift in scope wasn’t due to engineering inefficiency—it stemmed from the business analysts' prioritization sessions occurring after sprint commitments were made. A simple rescheduling of prioritization ceremonies—ensuring that business decisions were finalized before engineering teams committed to sprint goals. This small yet system-wide adjustment significantly improved delivery consistency and alignment—something that wouldn’t have been possible without examining the entire end-to-end process.

3. Shifting from Tactical Metrics to Strategy

There are many frameworks, methodologies, and metrics often referenced as critical to the engineering insights conversation. While these can be useful, they are not inherently valuable on their own. Why? Because it all comes down to strategy. Focusing on managing a specific engineering metric or framework (i.e. DORA or SPACE) is missing the forest for the trees. Our most successful customers have a clear, defined, and well-communicated strategy for their software engineering insights program—one that doesn’t focus on metrics by name. Why? Because unless a metric is mapped to something meaningful to the business, it lacks the context to be impactful.

Strategic engineering leaders at large organizations focus on business-driven questions, such as:

- Is this engineering investment improving customer experience?

- Are we accelerating revenue growth?

- Is this new approach or tool improving cross-functional collaboration?

Tracking software engineering metrics like cycle time, PR size, or deployment frequency can be useful indicators, but they are output metrics—not impact metrics. Mature organizations go beyond reporting engineering speed and instead ask: "Did this speed up product releases in a way that drove revenue?"

While challenging to measure, this is where true business value lies. A 10% improvement in cycle time may indicate progress, but if sales remain flat, did it actually move the needle? Instead of optimizing isolated metrics, engineering leaders should align their focus with overarching business strategy. If an engineering metric doesn’t directly map to a key strategic imperative, it’s worth reevaluating whether it’s the right thing to measure.

One of our retail customers accelerated the release of a new digital capability, allowing them to capture additional revenue a full quarter earlier than anticipated. Not only did this directly increase revenue, but the extended timeline of revenue generation created a long-term financial impact—a result that finance teams, investors, and the board highly valued. The team was able to trace their decisions back to insights derived from their engineering data, proving the direct connection between software delivery and business success.

Understanding the broader business strategy isn’t optional for high-performing engineering organizations—it’s a fundamental requirement. Through our developer experience surveys, we’ve observed a significant difference between the highest-performing organizations and the rest as it relates to how well developers understand the business impact they are responsible for delivering. Organizations that treat engineers as task-takers, isolated from business impact, consistently underperform—even if their coding efficiency is exceptional. The engineering leaders at top-performing organizations prioritize alignment with strategy and avoid the distraction of tactical metrics that fail to connect to meaningful business outcomes.

Learn how to shift from micro engineering adjustments to strategic business impact. Request a Code Climate Diagnostic.

Code Climate has supported thousands of engineering teams of all sizes over the past decade, enhancing team health, advancing DevOps practices, and providing visibility into engineering processes. According to Gartner®, the Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) platform market is expanding as engineering leaders increasingly leverage these platforms to enhance productivity and drive business value. As pioneers in the SEI space, the Code Climate team has identified three key takeaways from partnerships with our Fortune 100 customers:

- Engineering Metrics Are Not Enough

- Engineering leaders that adopt a Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) platform without a proper SEI strategy fail to extract value from the data

- Engineering leaders that adopt quantitative metrics without qualitative measures are missing the full picture

- Engineering leaders that adopt a Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) platform without a proper SEI strategy fail to extract value from the data

- Hands-Off Approach Falls Short

- Approaching an SEI platform as a traditional turnkey SaaS product does not ensure team success

- Organizations that lack collaboration with an SEI solutions provider often struggle to drive adoption and understanding of engineering insights

- Approaching an SEI platform as a traditional turnkey SaaS product does not ensure team success

- Insights Alone Do Not Drive Outcomes

- Engineering leaders often struggle to translate insights from an SEI platform into actionable steps

- Engineering leaders often struggle to align engineering performance to meaningful business outcomes

- Engineering leaders often struggle to translate insights from an SEI platform into actionable steps

Empowering Engineering Leaders at Enterprise Organizations

The above takeaways have prompted a strategic shift in Code Climate’s roadmap, now centered on enterprise organizations with complex engineering team structure and workflows. As part of this transition, our flagship Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) platform, Velocity, is now replaced by an enhanced SEI platform, custom-designed for each leader and their organization. With enterprise-level scalability, Code Climate provides senior engineering leaders complete autonomy over their SEI platform, seamlessly integrating into their workflows while delivering the customization, flexibility, and reliability needed to tackle business challenges.

Moreover, we understand that quantitative metrics from a data platform alone cannot transform an organization, which is why Code Climate is now a Software Engineering Intelligence Solutions Partner—offering five key characteristics that define our approach

- Tailored Solutions: We provide engineering solutions via quantitative insights and qualitative workshops that are specifically designed to meet the unique needs of enterprise engineering teams—moving beyond standard, black-box solutions.

- Strategic Collaboration: We enable our enterprise customers to build an SEI strategy, engaging with key stakeholders to align Code Climate’s solution and services with their broader business goals.

- Long-Term Partnership: Our strategic partnership with our enterprise customers is typically ongoing, focusing on long-term value rather than offering a standard insights platform. As an enterprise-level SEI solutions partner, we are invested in the sustained success of our customers.

- Expert Guidance: We offer expert guidance and actionable recommendations to help our enterprise customers navigate challenges, optimize performance, and achieve business goals.

- End-to-End Support: We provide comprehensive services, from advisory support and implementation to ongoing support and optimization.

A Message from the New CEO of Code Climate

"During my time at Pivotal Software, Inc., I met with hundreds of engineering executives who consistently asked, “How do I improve my software engineering organization?” These conversations revealed a universal challenge: aligning engineering efforts with business goals. I joined Code Climate because I'm passionate about helping enterprise organizations address these critical questions with actionable insights and data-driven strategies that empower engineering executives to drive meaningful change." - Josh Knowles, CEO of Code Climate

Ready to make data-driven engineering decisions to maximize business impact? Request a consultation.

Today, we’re excited to share that Code Climate Quality has been spun out into a new company: Qlty Software. Code Climate is now focused entirely on its next phase of Velocity, our Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) solution for enterprise organizations

How It Started

I founded Code Climate in 2011 to help engineering teams level up with data. Our initial Quality product was a pioneer for automated code review, helping developers merge with confidence by bringing maintainability and code coverage metrics into the developer workflow.

Our second product, Velocity, was launched in 2018 as the first Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) platform to deliver insights about the people and processes in the end-to-end software development lifecycle.

All the while, we’ve been changing the way modern software gets built. Quality is reviewing code written by tens of thousands of engineers, and Velocity is helping Fortune 500 companies drive engineering transformation as they adopt AI-enabled workflows.

Today, Quality and Velocity serve different types of software engineering organizations, and we are investing heavily in each product for their respective customers.

Where We're Going

To serve both groups better, we’re branching out into two companies. We’re thrilled to introduce Qlty Software, and to focus Code Climate on software engineering intelligence.

Over the past year, we’ve made more significant upgrades to Quality and our SEI platform, Velocity, than ever before. Much of that is limited early access, and we’ll have a lot to share publicly soon. As separate companies, each can double down on their products.

Qlty Software is dedicated to taking the toil out of code maintenance. The new company name represents our commitment to code quality. We’ve launched a new domain, with a brand new, enhanced edition of the Quality product.

I’m excited to be personally moving into the CEO role of Qlty Software to lead this effort. Josh Knowles, Code Climate’s General Manager, will take on the role of CEO of Code Climate, guiding the next chapter as an SEI solutions partner for technology leaders at large, complex organizations.

We believe the future of developer tools to review and improve code automatically is brighter than ever – from command line tools accelerating feedback loops to new, AI-powered workflows – and we’re excited to be on that journey with you.

-Bryan

CEO, Qlty Software

Technology is evolving very quickly but I don't believe it's evolving as quickly as expectations for it. This has become increasingly apparent to me as I've engaged in conversations with Code Climate's customers, who are senior software engineering leaders across different organizations. While the technology itself is advancing rapidly, the expectations placed on it are evolving at an even faster pace, possibly twice as quickly.

New Technology: AI, No-Code/Low-Code, and SEI Platforms

There's Generative AI, such as Copilot, the No-code/Low-code space, and the concept of Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) platforms, as coined by Gartner®. The promises associated with these tools seem straightforward:

- Generative AI aims to accelerate, improve quality, and reduce costs.

- No-code and Low-code platforms promise faster and cheaper software development accessible to anyone.

- SEI platforms such as Code Climate enhance productivity measurement for informed decisions leading to faster, efficient, and higher-quality outcomes.

However, the reality isn’t as straightforward as the messaging may seem:

- Adopting Generative AI alone can lead to building the wrong things faster.

- No-code or Low-code tools are efficient until you hit inherent limitations, forcing cumbersome workarounds that reduce maintainability and create new challenges compared to native code development.

- As for SEI platforms, as we've observed with our customers, simply displaying data isn't effective if you lack the strategies to leverage it.

When I joined Code Climate a year ago, one recurring question from our customers was, "We see our data, but what's the actionable next step?" While the potential of these technologies is compelling, it's critical to address and understand their practical implications. Often, business or non-technical stakeholders embrace the promises while engineering leaders, responsible for implementation, grapple with the complex realities.

Navigating New Technology Expectations and Realities

Software engineering leaders now face increased pressure to achieve more with fewer resources, often under metrics that oversimplify their complex responsibilities. It's no secret that widespread layoffs have affected the technology industry in recent years. Despite this, the scope of their responsibilities and the outcomes expected from them by the business haven't diminished. In fact, with the adoption of new technologies, these expectations have only increased.

Viewing software development solely in terms of the number of features produced overlooks critical aspects such as technical debt or the routine maintenance necessary to keep operations running smoothly. Adding to that, engineering leaders are increasingly pressured to solve non-engineering challenges within their domains. This disconnect between technical solutions and non-technical issues highlights a fundamental gap that can't be bridged by engineering alone—it requires buy-in and understanding from all stakeholders involved.

This tension isn't new, but it's becoming front-and-center thanks to the promises of new technologies mentioned above. These promises create higher expectations for business leaders, which, in turn, trickle down to engineering leaders who are expected to navigate these challenges, which trickle down to the teams doing the work. Recently, I had a conversation with a Code Climate customer undergoing a significant adoption of GitHub Copilot, a powerful tool. This particular leader’s finance team told her, "We bought this new tool six months ago and you don't seem to be operating any better. What's going on?" This scenario reflects the challenges many large engineering organizations face.

Navigating New Technology Challenges and Taking Action

Here's how Code Climate is helping software engineering leaders take actionable steps to address challenges with new technology:

- Acknowledging the disconnect with non-technical stakeholders, fostering cross-functional alignment and realistic expectations. Facilitating open discussions between technology and business leaders, who may never have collaborated before, is crucial for progress.

- Clearly outlining the broader scope of engineering challenges beyond just writing code—evaluating processes like approval workflows, backlog management, and compliance mandates. This holistic view provides a foundation for informed discussions and solutions.

- Establishing a shared understanding and language for what constitutes a healthy engineering organization is essential.

In addition, we partner with our enterprise customers to experiment and assess the impact of new technologies. For instance, let's use the following experiment template to justify the adoption of Copilot:

We believe offering Copilot to _______ for [duration] will provide sufficient insights to inform our purchasing decision for a broader, organization-wide rollout.

We will know what our decision is if we see ______ increase/decrease.

Let’s fill in the blanks:

We believe offering Copilot to one portfolio of 5 teams for one quarter will provide sufficient insights to inform our purchasing decision for a broader, organization-wide rollout.

We will know what our decision is if we see:

- An increase in PR Throughput

- A decrease in Cycle Time

- No negative impact to Rework

- No negative impact to Defect Rate

Andrew Gassen leads Code Climate's enterprise customer organization, partnering with engineering leaders for organization-wide diagnostics to identify critical focus areas and provide customized solutions. Request a consultation to learn more.