Hillary Nussbaum

For our series, 1:1 with Engineering Leaders, Code Climate and Codecademy for Business are speaking to managers and VPs about their career journey, leadership strategies, and advice for the next generation of engineers. Check out our previous interviews with Tara Ellis, Manager, UI Engineering at Netflix, Brooks Swinnerton, Senior Engineering Manager at GitHub, Gergely Nemeth, Group Engineering Manager at Intuit, Lena Reinhard, VP of Product Engineering at CircleCI, Andrew Heine, Engineering Manager at Figma, and Mathias Meyer, Engineering Leadership Coach.

Below is an excerpt from our conversation with Anchal Dube, Senior Engineering Manager at Zocdoc. Anchal shared her thoughts on the shift in mindset necessary to take on a manager role, the importance of having the right expectations, and the similarities between managers and tug boats. Edited for length and clarity.

For Anchal’s advice for early-career engineers, visit the Codecademy blog.

Tell us about your current role, and your career journey up to this point.

I’m a Senior Engineering Manager at a Zocdoc, and currently I’m overseeing a couple of different teams. One team is focused on the Zocdoc video service we launched in response to the pandemic and the fact that a lot of care suddenly needed to go virtual. It’s something that we built and launched over a two-month time period, whereas more typically this would have been a two-year roadmap. The other team focuses on our provider touchpoints and how we can use the relationship that we have with our providers to build a better connection with their patients.

In terms of my journey, I have a Bachelor’s in Computer Engineering and a Master’s Degree in Computer Science. I started out in the healthcare space, working at Epic, which is an EMR company based out of Madison, Wisconsin. I worked there as a Software Engineer and then as a Team Lead for a little under five years. That was my first foray into a leadership role.

Early on, there was a honeymoon period where I was really excited about what I really perceived as the next step of my journey, with a promotion and more responsibility. But about nine months into that, I really started questioning whether the role was for me, and whether I wanted to continue. Around the same time, for family reasons, I was looking to move to the East Coast. And so when I moved to Zocdoc, I actually came here as an IC.

I joined as a Senior Software Engineer and wanted to continue down the individual contributor path, but was impacted by an incredible manager and mentor I had at the time. He really took the time to understand my challenges and pain points from my previous leadership role. And he gave me a lot of motivation and advice on how to navigate that transition again, and to do it much more successfully the second time around.

So after being at Zocdoc for about two years or so, I went the management route again, starting with the team that I was already working on as an IC.

What was it that turned you off of managing the first time around, and how did that change, other than having a great mentor? Do you feel like it was circumstantial, or a mindset that you needed to change personally?

I think mindset was definitely a challenge. One thing that I recognize now, that I don’t think I did in my first stint as a leader, was that I really needed to take a step back from owning everything directly. My path to creating impact is not going to be by executing on a given project, but by empowering my team so that they can do so. And the skill set that I need to rely on is less computer science and computer engineering fundamentals, but more around how to create influence within a group of people.

That shift was something that I didn’t recognize as necessary early on. In working with my mentor a few years later, he really instilled in me the importance of that skillset in particular. And I had to get into the right headspace for navigating some of those challenges, and not allowing myself to get sucked into a lot of frustration when I felt like I was taking on too much or juggling too many things.

Do you miss being more directly involved in the technical day-to-day, or in the kind of execution where you can check a box, as opposed to manager duties, which aren’t usually like that?

That’s evolved over time. Early on I definitely still missed being hands-on with coding. And so every once in a while, usually at least once or twice a week. I would pick up a small thing that needed to be edited on the website, or a small change that I could make.

I’m going to use an example from Grey’s Anatomy — there’s a scene where the doctors are talking about transitioning into the Chief role. And one of the pieces of advice that the former Chief has is, “start your day cutting. Start your day with surgery, and then let the rest of the day be given over to administrative stuff.” That’s something that helped me early on, so I was able to keep doing something that I really found rewarding and fulfilling. And over time, as I think about what is most important to me, and what is most important in order to make myself effective at Zocdoc for my teams, the more I’ve come to enjoy what I consider “people engineering,” as opposed to software engineering.

And so I’ve gradually shifted my balance too, in terms of what I enjoy and what I want to focus my time on.

Did you always know that you wanted to be a manager or was it something that just happened to you the first time around?

It was part of my expectations of the path to advancement and career growth. Through that lens, I wanted it, but I do think that it was a little bit misplaced to think of it as a linear growth trajectory, as opposed to recognizing how much of a role shift it is. That recognition is super important.

So now, as I mentor future leaders at Zocdoc, people who are going through a similar transition period, that’s one thing that I really try to keep front and center for them — it’s not really just the next step in the career ladder, it’s a pretty significant role shift that requires a shift in how they approach the problems that they’re going to be solving and changes the skillset that they’re going to need to rely on to get to the next level of success in their careers.

And what do you see as the role of a manager on an engineering team?

I’m going to be terribly mixed with my metaphors here, but I think that it’s a combination of coach and cheerleader. I see managers as the little tugboat that’s trying to help the larger ship, the team, navigate unfamiliar waters. It’s there all of that time to figure out where the obstacles lie, and to steer the ship away from them. So really it boils down to the manager figuring out whatever is needed to empower the team, so they can deliver at their best level.

Is there a difference in your mind between being a manager and a leader? And if so, what is it?

You can definitely be a manager without being a leader. And I think leadership comes down to the kind of thought leadership that you provide within a team context. I’ve noticed how the types of questions that I ask my team really start to influence what they consider important on a day-to-day basis.

One of the things that I took on as a side role at Zocdoc was to become a lead on our Operational Excellence Guild. And so I would bring that lens to my conversations with my team, and it was very telling to see how quickly my team adapted to that, and how those considerations became very top of mind for them as well. That illustrates to me the difference between just being a manager, where you’re doing very day-to-day organizational management things, and learning to be a leader and bringing in an element of influence.

What are the biggest challenges that you’ve faced as a leader?

The largest challenge is always that there are so many different things that are important that I would love to devote time and resources to, but we’re almost always capacity constrained. I imagine this is true for companies of all sizes, although I feel like I’ve seen that much more kind of in the Zocdoc context, where we’re still a relatively small team.

There are a lot of things that my team legitimately cares about, like keeping our tech debt appropriately low, or maintaining a certain level of code hygiene, or even which bugs we’re fixing and what type of turnaround time we’re fixing them on. But it’s a constant balancing act. It’s a constant juggle to balance that against everything that is most relevant to the bottom line of the business. We also have to think about how to keep our overhead low enough so we can continue to execute towards our main goals without getting too bogged down by the challenges posed by an unhealthy code base.

You’re talking a little bit about team goals — how do you help developers grow both as individuals and as a team?

A lot of that is very much a collaboration between myself and each of my team members. And it also hinges on how driven they are, and how much they understand where they want to be headed. I always find that for people who really understand what their trajectory is and know what they’re looking for, I can provide them with much more targeted feedback. And there are definitely other people who are really just figuring it out as they go, and for those individuals, it’s much more based on our conversations, and me picking up on the things that they are enjoying, so I can help them identify those areas and double down on their areas of strength.

How do you gain an understanding of what your team is working on at any moment in time, and then perhaps equally as important, how everybody is feeling about how things are going?

That’s been especially interesting with the pandemic and going remote basically overnight. I use my 1 on 1s with my team to get a feel for how they’re doing and what sorts of challenges they’re running into, whether it’s at work or even in their personal lives. Especially early in the pandemic, one of the things that I wasn’t recognizing very early on was how much people were starting to feel burnt out.

One thing that I did notice as a symptom was that a lot of people were working later hours than they typically would have been. And so without even really thinking about what the impact of that was, I made sure to impress on everyone the fact that it was okay to take time away from work and to just attend to their needs as well. And it was very interesting when multiple weeks later, the team brought that up as something that they found very, very helpful to course correct, and to give themselves space to take a breath and figure out what they needed to do to deal with everything that was changing around them.

Yeah, that’s something that we’ve heard a lot, and we dealt with it here as well. What advice do you have for new managers or people looking to shift their career path and become managers?

Yeah, I think I’ll go back to the thing that I said earlier, which was: Do they have the right set of expectations about what the role entails? A lot of that ultimately comes from talking to people who have somewhat recently made that transition, because they’re in the best position talk about what they enjoyed and what they didn’t and how different it was from their expectations. Having those conversations can be really crucial to helping the next set of people recognize what some of those pitfalls might be.

Apart from that though, for anyone who is interested in going down that path, my advice would be to work with their current manager to figure out what their team’s needs are on the leadership front. What are the areas where the team really needs support? Because like I said, I definitely see Engineering Managers roles as being about navigating a lot of obstacles. And so identifying those through a conversation with someone who’s already in that role is a great first step towards taking a stab at helping the team navigate through one or two of those obstacles.

For more of Anchal’s advice for the next generation, visit the Codecademy blog.

Engineering managers often rely on subjective clues to assess how their team is doing. But decisions made based on gut feel and imperfect measurements are less than ideal — sometimes they result in team success; other times they result in disappointment. Subjective measures need to be supplemented with objective data; with a combination of the two, managers are more likely to make choices that benefit their teams.

When baseball managers learned this lesson, it got the Hollywood treatment. Moneyball depicted the metrics-first approach to baseball management popularized by Billy Beane, former General Manager of the Oakland A’s. Employing three lessons from Beane’s management approach can help engineering leaders drive productivity and efficiency on their teams.

Lesson #1: Use objective metrics

Beane gained notoriety for prioritizing statistics over scouts’ instincts and consistency over flash. This approach is rooted in sabermetrics — the field dedicated to “the search for objective knowledge about baseball” and statistical analysis of the sport.

Though sabermetrics was founded by baseball fans, Beane applied this predilection for objectivity to managing his team. Rather than relying on scouts’ instincts, intangibles like a player’s footwork, or prestigious metrics like batting average, Beane favored a selection of under-appreciated metrics more closely correlated with consistent results.

Historically, software development has been a field lacking in objective measurements. Classic workload estimates like T-shirt sizes can be useful for internal scoping but are too subjective to translate throughout an org; one team’s size “XL” project is another team’s “Medium.”

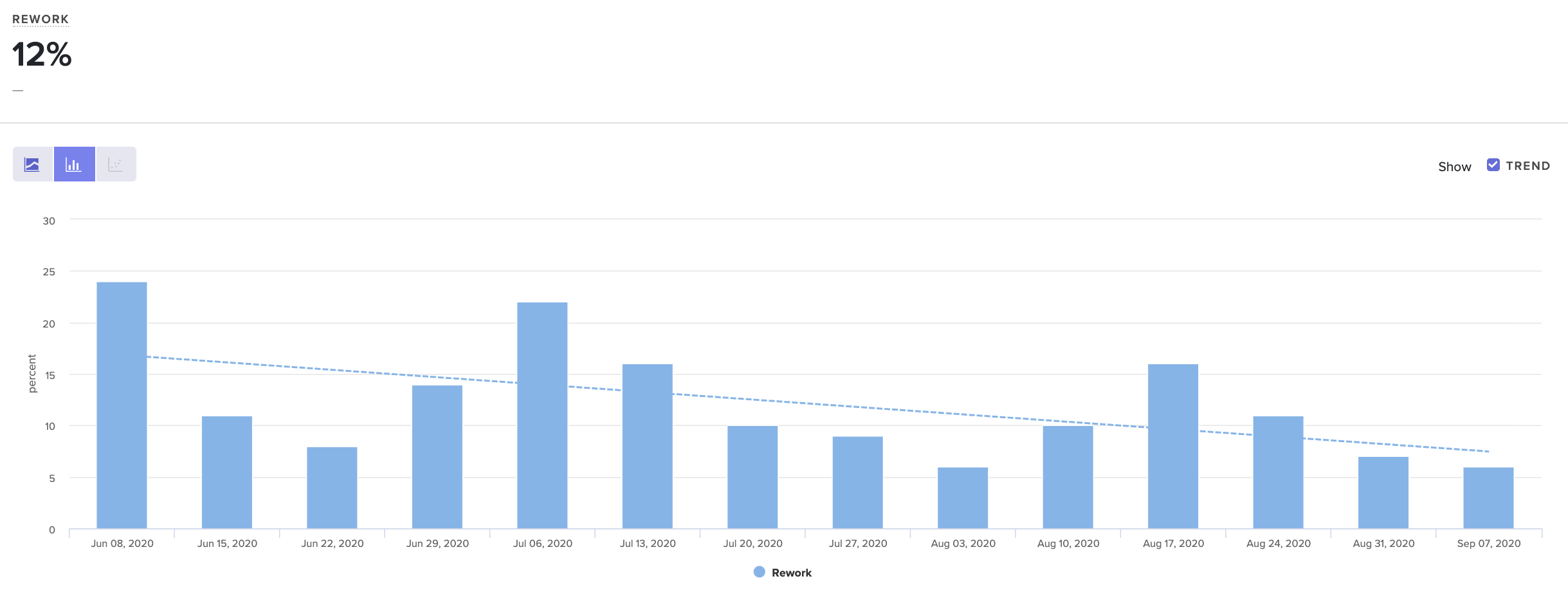

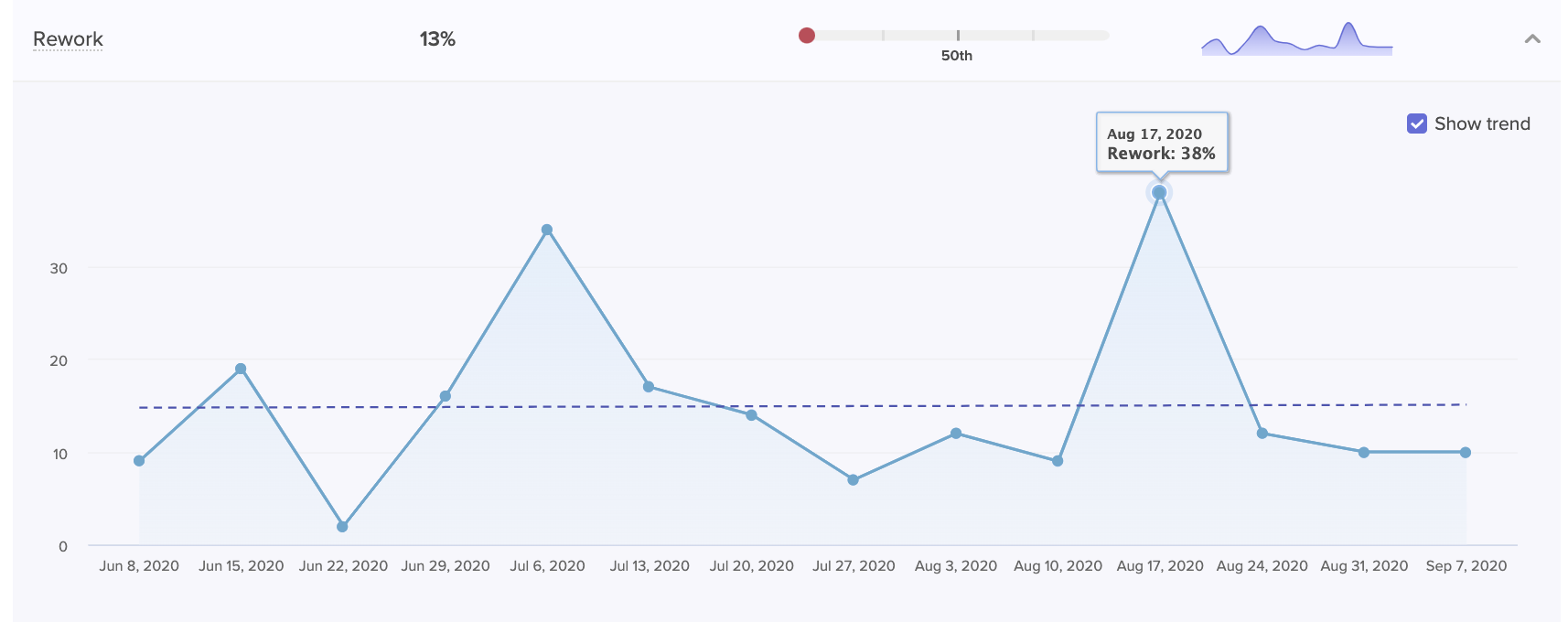

Engineering leaders need objective measurements. Our version of sabermetrics involves analyzing the data generated by our own VCS, which is full of objective data about the number of Commits logged in a given period, or the length of time a Pull Request stays open before it’s picked up for review. Objective measurements can help engineering leaders measure progress across teams, projects, and quarters, and are instrumental in setting and achieving effective departmental goals.

Lesson #2: Focus on leading indicators

Of course, not all objective data is equally useful; one of the hallmarks of Beane’s strategy involved the careful selection of metrics. When recruiting, most managers looked at a player’s batting average — the number of times they hit a ball into fair territory and successfully reached first base, divided by their number of at-bats. Beane looked at their on-base percentage, or OBP, a measure of how often a batter reaches first base, even if they get there without actually hitting the ball.

A player must be a good hitter to have a good batting average, but what puts them in a position to score a run is getting to first base. From a data-first perspective, the value of an at-bat is not in the hit itself but in the player’s two feet making it safely to first.

Similarly, to the rest of the organization, your team may be defined by their most eye-catching stats and praised when they deploy a much-anticipated revenue-generating feature. But just as a player’s batting average doesn’t account for every time they get on base, a list of features completed can only reveal so much about your team’s productivity.

The true measure of your team’s success will be their ability to deliver value in a predictable, reliable manner. To track that, you’ll need to look past success metrics and dig into health metrics, measurements that can help you assess your team’s progress earlier in the process.

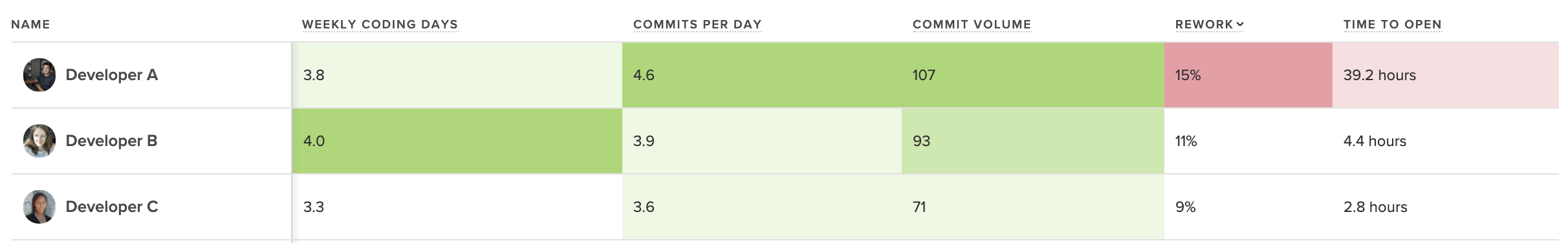

For example, an engineering manager might look at “Time to Open,” which is a measure of the period between when a developer first logs a Commit in a Pull Request and when that Pull Request is finally opened. Code can’t move through your development pipeline until a Pull Request is opened, and smaller Pull Requests will move through your pipeline more quickly.

Time to Open is similar to OBP. It’s not a prestigious metric, but it’s a critical one. Just as you can’t score if you don’t get on base, your team can’t deploy code that never makes it to a Pull Request. As a manager, you need to make sure that developers are opening small, frequent Pull Requests. If they’re not, it may be worth reinforcing good code hygiene practices across your team and speaking directly with developers to determine whether there’s something particular that’s tripping them up in the codebase.

Lesson #3: Use Metrics in Context

Of course, Beane’s approach wasn’t perfect. Metrics alone can’t tell you everything you need to know about a potential player, nor do they hold all of the answers when it comes to engineering. Data is useful, but leaning too strongly on one metric is shortsighted.

Though Beane was famous for seeing the value in a player’s OBP, there’s also evidence that at times, he relied too heavily on that one metric. Not every college player with a strong OBP was cut out to play professional baseball. While a scout might be able to differentiate between a promising young athlete and one who was unlikely to succeed, a metric can’t make that distinction.

As an engineering leader, you need to rely on a combination of instinct and data. Start with how you feel — is your engineering team moving slow? — and then use metrics to confirm or challenge your assumptions. When something is surprising, consider it a signal that you need to investigate further. You might need to re-evaluate a broken process or find new ways to communicate within your team.

Beane’s approach to managing his team was headline-grabbing because it was revolutionary, representing a major shift in the way fans, commentators, and managers thought about the sport of baseball. Many of his groundbreaking strategies are now commonplace, having been adopted across the league.

Data-informed engineering leadership is still at that revolutionary stage. It’s not standard practice to use objective engineering metrics to assess your team’s progress or guide its strategy, but it will be.

For our series, 1:1 with Engineering Leaders, Code Climate and Codecademy for Business are speaking to managers and VPs about their career journey, leadership strategies, and advice for the next generation of engineers. Check out our previous interviews with Tara Ellis, Manager, UI Engineering at Netflix, Brooks Swinnerton, Senior Engineering Manager at GitHub, Gergely Nemeth, Group Engineering Manager at Intuit, and Lena Reinhard, VP of Product Engineering at CircleCI.

Below is an excerpt from our conversation with Mathias Meyer, Engineering Leadership Coach and former Co-Founder, CEO, & CTO. Mathias shared his thoughts on working with coaches, and the difference between influence and authority. Edited for length and clarity.

For Mathias’s advice for early-career engineers, visit the Codecademy blog.

Tell us about your current role, and how you got there.

My current role is a little complicated because I’m in the middle of a sabbatical. I’ve been coaching engineering leaders and founders — folks who’ve had a similar trajectory as I’ve had —and working with startups here and there. Previously, I had several roles. One of them was CTO at a company out of Santa Monica, Reaction Commerce, which got acquired earlier this year. Prior to that, I was founder and CEO of Travis CI, a company in Berlin. Both had fairly distributed teams.

At Travis CI, I started out as an engineer and without any aspiration to be a CEO at some point, to dive deeper into management. I started out focusing on infrastructure and automation, and always had an interest and a knack for debugging production systems. Some of that translated pretty well into a growing company that needed some sort of leadership and eventually a certain level of management. Over time, we split up these responsibilities, and some of them ended up with me. At Travis CI, the title of CEO came along with them. As it is with a founder role, it was all over the place, focusing here for three months and then focusing there.

Leadership and management just became interesting over time, with interesting skills and personal traits to learn and sharpen.

What skills did you already have that were helpful as a manager, and what did you need to work on?

I would say I probably didn’t have any skills to speak of. We were five co-founders, and we were all engineers, that’s just where we came from. What I had was an interest in organizational behavior, organizational psychology, and company culture. Those things existed in my mind, but they weren’t things that I had practiced in any way.

The other thing that I mentioned previously is a knack for debugging, which is a handy trait when you’re a manager. It was the one thing that I brought into that role that I was good at that was very useful. The rest was just years of working with a coach, years of talking to other founders and CEOs, and learning while failing a lot of the time as well.

What do you see as the role of a manager? Does it change if that person’s managing a team, or managing a department?

I do think the role changes. When you manage a team, your concerns focus a lot more on your team. You know what their priorities are, what their personal growth paths are, how they support the organization and the business, so on and so forth. You focus a lot on the people that report to you. As you move away from just managing a team and towards managing a team of teams, your focus is a lot more towards the horizon.

When you’re an engineer, most of your focus is on what’s right in front of you. When you’re a team lead, you look a couple of weeks, maybe a couple of months ahead. But as you move further and further away from the action of actually writing code, you focus on more strategic things like having a strategy in place so that your entire team knows what’s going to happen in the next 12 to 18 months. Or you focus on budgeting and living up to these budgets, and interacting more with other parts of the company.

The further you move away from the engineering side, the more time you will spend doing things that have nothing to do with engineering. Not even what your team is doing, though you’re making sure that what your team is doing ties well into the rest of the organization.

Is there a difference between being a manager and a leader? If so, what is it?

I do think there is a difference. Simply put, I would say a leader can rally people to do something they wouldn’t otherwise do. That’s a useful skill for a manager, but you don’t need to be a manager to be a leader. Having leaders on your team that are not managers is actually very useful because for you as a manager, that means you don’t have to do everything. Say you have a Tech Lead on your team, that is someone who can actually do that, lead, rally people around a certain thing, or Product Managers, those kinds of folks, those kinds of roles. Those are all leadership roles, but they’re not management roles.

What do you see as the biggest challenges for leaders? Not the logistical challenges that a manager might also face, but the more people-related, motivational challenges.

As a leader, you don’t necessarily have the authority that comes from the management role. I think every Product Manager will be able to attest that the most difficult part, or one of the more difficult parts, is to actually get people to do something when you don’t have the direct authority to tell them what to do. In a classic hierarchical organization, it’s always the person above you who has the authority to tell you what to do. So as a leader, you only have influence, you can only try to convince people that something is a good thing and something should be done, but you can’t just go ahead and tell them well, do that.

That kind of leadership, leadership by influence or suggestion, is actually a lot more powerful. If you can actually convince people that something is a good idea, or you can make them realize it their own, the effect is a lot more powerful than telling someone to do something. Because then they’re convinced themselves that this is a great idea, this needs to get done. They’re motivated to do it. This is where I think leadership and management are different things. If you as a manager can have the skills or learn the skills of being a leader, influencing people, convincing people, not just telling them what to do, I think that’s a very useful and powerful combination.

Let’s talk a little bit about what you are doing now. A lot of the engineering leaders I’ve spoken to have mentioned that they have worked with leadership coaches. What is the role of a leadership coach?

I can speak from my experience of working with a coach. A big part of growing in leadership and in management is growing yourself. Or as some people say, scaling yourself.

There are challenges involved in being responsible for first five people, then an organization of 20 people, and maybe at some point 50 or a hundred people that are very lonely challenges. If you’re somewhere in middle management, maybe you have a support group in your organization, or maybe you have a support group outside of the organization, which are definitely both things that I would highly recommend. But the higher up you go, the more lonely everything is, and the harder it becomes to find someone to talk to, to complain to, and to speak to about whatever personal challenges you face in increasing responsibility, or having to deal with frustrating people on your team.

It’s useful to have someone who’s impartial, whose only concern is you and not necessarily the organization as a whole, to provide an outside perspective, to be a sounding board, or to call you out. If you’re procrastinating on something, if you’re avoiding a difficult conversation, if you don’t actually know how to have a difficult conversation, a coach can help. They can give you ideas or pull them out of you so you can actually make it through what I like to call the crucibles of management, like having to fire someone, or having a difficult conversation with your co-founders, or with a peer in the organization.

Those things don’t come lightly or easily to everyone, probably not to most people. A coach can be a useful guide through those situations. It certainly has been for me. I’ve been working with a coach for five-and-a-half years, and it was probably one of the most impactful and useful things for me personally, to have that sounding board, to have someone to complain to. You can’t complain to the people on your staff, that would be wrong. But sometimes you just need to vent. Sometimes you just need to vent to someone, and then you can move on and you can figure out what to actually do about it.

For all that entire basket of things, it is very useful. Even if it’s just an hour every two weeks, which is the cycle that I’ve been in for a long time. It’s having this dedicated time that is only for yourself, which is something that most managers and leaders don’t afford themselves. They’re always in service of others, even though they themselves have challenges that they need to figure out.

How do you find a coach who’s a good fit? How do you know if they’re the right person?

It takes a couple of sessions to figure that out. Probably a lot of coaches will have an initial conversation with a new client just to see if there’s a general fit. It depends on what you are actually looking for. Some people say they’re looking for a coach, but they’re really looking for a mentor or an advisor. Someone where they can go, “I’m in this situation, have you experienced that as well? What did you do about it?” That’s more of a mentoring or an advisory role. Usually you figure that out in the first conversation, but I think just like with hiring people, it takes some time of working together. It doesn’t take a long time, but you do need a couple of sessions with a coach to just see if it clicks.

What advice do you have for new managers or people who are looking to shift paths and become managers?

I would refer a little bit to the other question for this, but something that I’ve experienced is that people from the engineering side sometimes look to management roles to gain authority, to gain that hierarchical advantage of being able to tell people what to do. I wouldn’t say it’s a common thing, but it happens. Some people are frustrated that they can’t tell other people what to do, and think being able to pull rank would be useful.

My advice to those folks usually is, that’s not how it works. Even if you do have the authority, people will not just go ahead and do what you tell them to, especially if they disagree with it, or if you can’t explain why it is a good idea. They might still do it if you can’t explain it, but they’re not going to be happy about it, and they’re not going to support the idea. Going into management to gain authority is not a useful motivation. If you go into management, you should have an interest in figuring out people. That’s really the most interesting and also the most frustrating aspect of management — you have to work with a lot of different people, and you have to figure out how each and every one of them ticks. You have to figure out ways to work with different people within your team, people who report to you and people outside of the team that might have more influence over something than you do.

Again, there could be a tendency to go higher up so that you have even more authority, but it will never change. It will never be different unless you’re maybe at the complete top. Even then, you can’t just tell an entire organization, “do that,” and expect that the organization will drop everything and just go for it. It’s just not how it works, and you still have to work with people. That requires patience. It requires curiosity. Be ready to interface with people a lot, and to be in a lot of meetings.

For more of Mathias’s advice for the next generation, visit the Codecademy blog.

For our series, 1:1 with Engineering Leaders, Code Climate and Codecademy for Business are speaking to managers and VPs about their career journey, leadership strategies, and advice for the next generation of engineers. Check out our previous interviews with Tara Ellis, Manager, UI Engineering at Netflix, Brooks Swinnerton, Senior Engineering Manager at GitHub, and Gergely Nemeth, Group Engineering Manager at Intuit.

Below is an excerpt from our conversation with Lena Reinhard, Vice President of Product Engineering at CircleCI, who shared her thoughts on leadership, running distributed teams, and helping team members level up. Edited for length and clarity.

For Lena’s advice for early-career engineers, visit the Codecademy blog.

Tell us about your current role and how you got to where you are.

Lena Reinhard, Vice President of Product Engineering, CircleCI: I’m VP of Product Engineering with CircleCI. I joined CircleCI in June, 2018, so I’ve been here for two years and a quarter. I initially joined as Director of Engineering to help scale the organization, and then formally moved into this role in March this year.

I lead a globally distributed team, and the biggest part of my work is making sure that everyone in the organization understands our strategy direction, where we’re looking to go, and that they have the context that they need.

I noticed your personal website showcases some of your creative hobbies, so I’m curious, how do you blend the creative and the technical sides of your interests? Is there a creative side to engineering? To leadership?

I am not an engineer myself, that’s one thing probably worth highlighting. I have dabbled in engineering, but I am not as good as even our more junior engineers on the team, and it’s also not my main job. Of course there’s a lot technical about my work, and a there’s a lot that’s about the business side of things, but at the same time, as you mention, I do have that urge to be creative and live out those things.

To me, it’s more about what being creative actually means. A lot of my job is about being imaginative and using that imagination to solve problems. There’s a lot of really interesting problems to solve, and to solve at scale. I also have to be imaginative about not only what we’re seeing today, but also what’s to come: How’s the organization going to evolve? What does that mean for our business overall, for the people on our teams? So I use a lot of creativity to approach problem-solving.

I make time every day for strategic thinking. I usually start my day with that, doing some free-form writing, then working through a few questions that I answer every day around how the organization is doing, and what I need to pay more attention to.

A big part of my role is also about imagining the organization we want to be and helping people understand that. And then I work with my team to determine how we’re going to get there.

Can you talk a little bit about how you came to be a manager? Where did you start, and then at what point did you start managing people? And did you know that you always wanted to do that?

I have always gravitated towards leadership. I used to lead projects in school, and in the sports that I did, I was the captain of the team. But I never thought I would be a manager. I wouldn’t have known what the role would entail, and what that actually would mean, I would’ve thought it meant bossing people around all day because of the kinds of things you see in movies.

Early on, I started by mentoring some people and coaching trainees at one of my first jobs, then I moved towards growing and managing open-source communities, and slowly gravitated towards more formal leadership roles. I ended up co-founding a company and becoming a CEO there, and with that it became a bit more formalized. From there I moved onto building engineering teams.

I built skills around managing people, so things like project management, how to work with people, dealing with conflict, setting direction, and those kinds of things. I developed those skills through other roles, and so I had kind of accumulated important skills and traits by the time I actually moved into a management role. It wasn’t a career goal, but I’m really glad I ended up there.

That seems to be a common theme. People tend to not know what managers do, or don’t trust them.

I think I’ve learned the most about being a manager from the worst managers I’ve had. Having talked to many managers about this, it also seems to be a bit of a common trait. The actual training is not really formalized, and there’s not necessarily been a lot of role models.

I also think there’s been a big shift in management’s role, even just over the last five years, let alone the last 10 or 20. My understanding of how management works and what makes a good manager has changed dramatically from where I am now versus the first Hollywood movies I saw with managers yelling at people.

What do you believe is the role of a manager on an engineering team, if their role isn’t to be the most senior technical expert? And then, what’s the role of a leader, and what’s the difference between the two?

Management is a role, it’s a function, and it comes with a certain set of responsibilities and accountability. I personally treat it very distinctly from leadership, because leadership in itself is a very distinct skill. It’s a way of behaving yourself, conducting yourself in the world, and it’s also about how you interact with others. Ideally managers are leaders, but not all leaders need to be managers. I often tell my teams, because we’re a globally distributed team, I believe we need leadership at all levels. We have a career growth framework for engineers where leadership skills are a trait that’s required of more junior engineers, up to being very senior, because I think it’s a fundamental element of what we need to carry the organization forward as a distributed team. The more people are connected with what we’re looking to do, the more they can understand that purpose and rally the rest of the team, the better for us. That’s why I encourage people to build out leadership skills, no matter what role they’re in.

I also think that it’s important for engineers specifically to be able to grow their careers without having to move into management. I view management and engineering as two distinctly different career paths, and I’m very happy to support people switching back and forth between them — we’ve had that multiple times in my current organization and it’s been really great — but it shouldn’t be that in order to move forward and progress in your career you have to become a manager. I think it sets people up for failure, worse case, and it sets them up for doing work that they don’t want to do because it’s just not everyone’s cup of tea. I like my job, but I also know not everyone wants it.

Managers are ultimately responsible and accountable for the business success of our teams. We have to focus on connection, communication, and collaboration on teams. There’s a lot of research, of course, on high-performing teams and what those teams need to be successful, but basically it’s about supporting teams in growing and becoming cohesive, helping engineers on the team grow, and helping teams deliver against the business’s goals. And then it’s everything that goes into that, because that’s, surprisingly, a lot of work.

What are your biggest challenges as a leader?

The one thing I keep saying is just scale. I lead an engineering organization at a hyper-growth company. We’ve been in a state like that for a couple of years now, and it impacts us in a variety of ways. It impacts us from an organizational perspective, since we want to make sure we’re appropriately supporting the people who we already have in the organization, as well as the ones that we’re looking to bring on in the future. And so that’s related to our processes and how we hire and onboard, and how we support career growth.

The other side of it is of course the technical side, making sure that our systems are set up to support the user base that we have, as well as the user base that we’re striving to have in the future.

So scale is definitely a big thing because it comes with a lot of change. It basically means being in a state of continuous change, always evolving and always adjusting how we operate as a team. Within that, I also have to maintain a good sense of what’s going on, since I’m relatively removed from a lot of other leaders in our organization.

With the growth that we’re going through, I also think a lot about scaling culture. We want to maintain parts of our culture, but then also constantly adapt in a way that’s healthy and that’s aligned with our values. Because I also don’t believe that trying to preserve the culture that you had as an organization when you were 20 people should be the goal.

We also have to make sure that we are always working on the most impactful thing for our customers, as well as for our organization. In a state of hyper growth, it’s easy to get into an “everything is important and urgent” mode, and it’s a challenge to work through that, for myself but also for my team, making sure that they know the priorities and that they’re able to shift their work accordingly.

I also put a lot of work into managing my reports, my staff, and my peers, and then of course upwards and then around into other parts of the company. That’s probably one of the biggest parts of my job.

Are any of these challenges remote-specific? You mentioned you’re a globally distributed team, so how does that complicate things for you?

It complicates everything. I love it, and I always feel like I need to add that as a disclaimer. I’m a big fan of distributed teams, but it also means we have to be more mindful of how we work. We have to be a bit more intentional, because stuff just doesn’t happen organically. My remote-specific challenges are mostly around time zones. I fortunately have an assistant who helps with the logistics of global distribution, which has been great, but that’s more the day-to-day.

The other big challenge is everything around change management and cascading communication. In a co-located team, at least up until the end of last year I guess, people could easily summon everyone into a room and say, “Well, here’s the change and here’s what’s happening,” and then everyone gets on with their day. That’s of course a very simplified example, but for us, anything that we’re looking to change usually requires quite careful planning.

Especially in a constantly evolving environment, we also have to be mindful that there are limitations to how much change an organization can digest at any point in time. We try to be strategic about where we think we can evolve to a desired status quo, versus where we actually need to change something.

This is a very broad question, but how do you drive high performance on your team, and how does that change if you’re working with an individual or the team as a whole?

There are a couple different frameworks. One is a career growth framework that we use for goal-setting and expectation-setting conversations on a quarterly basis, and then we do check-ins again over time. We also use that as a basis for 360 feedback and career growth conversations for the longer term. So that’s one pillar, which is more towards the individual.

At the team level, we do OKR-setting as a goal framework, also on a quarterly basis. Though we don’t use OKRs at the individual level, we do try to align individual goals towards the team’s OKRs. So, for example, if a team has goals around delivering on a specific service and someone on their team wants to get better at knowledge management, they might work on documentation around that specific service, or make sure that they’re onboarding someone new to that area.

We try to connect the individual’s career goals with what the team is actively working on. It helps create opportunities for people to work on their career goals in the short term, rather than pushing that down the line.

We also use a lot of other practices from DevOps around high-performing teams and DevOps culture. So things like retrospectives. Check-ins on the team side are really important as well. Teams need to connect and build relationships and focus on learning continuously together.

We also have an internal mentoring program, and have expectations in the career growth framework around learning to be a mentor or mentee.

Do you use engineering metrics at all on your team?

Yeah. We make a CI/CD product, it would be a shame if we didn’t.

That’s very true. Can you elaborate a little more on how you use them, and how that works on your team?

We have been moving towards using more and more metrics over time. For me, that’s just been a part of maturing as an organization. I also think it’s a natural side effect of growing to a point where not everyone knows what’s going on everywhere at all times anymore. Plus, I also think part of maturing is about evolving our practices, and measuring what matters is a good industry practice. It’s probably one of the better ones. So yeah, we’ve been gradually quantifying much more.

We use OKRs. We are also building out technical backlogs for the teams with technical initiatives with measurable impact. We utilize different delivery metrics and engineering metrics, including the standard DevOps metrics set, as well as others around team health, and services health. It’s a relatively broad set, and I would also say it keeps evolving. We use them, in addition to them being good practice, because we’re evolving as an organization.

They’ve become an increasingly important factor in measuring team health and the overall health of the organization, because it helps us understand how teams are doing against their goals. But also, for example, we measure how the teams are investing their capacity across new features, escalations, and technical debt and maintenance. It helps us plan. It also helps from a staffing perspective, knowing if teams are in need of more support.

So yeah, metrics are a good tool for both spot-checks on the current state, as well as for planning. It helps in terms of understanding how long work is out, how well we’re doing on estimating our ability to deliver, how long things are going to take, those kinds of things.

What advice do you have for new managers, or for people who are looking to change their career path and become a manager?

I’d say learn a lot and try to constantly level up. Like I read different newsletters, I read books. Books on management and all facets of it. I’ve also been working with career coaches for many years. I’d say, it’s more of a pull situation than a push situation. People aren’t necessarily going to give a lot of support, and in many organizations there’s no structured growth frameworks. So finding ways to level up is really important.

Investing in building relationships is also really crucial, especially in distributed teams. Make sure to build connections with important stakeholders, and of course with the team that you’re leading as well. But the relationships are going to be the main currency that helps a manager be successful.

One point that I’ve coached a lot of engineers through has been recalibrating internal success measures, and what makes them feel accomplished. For me at least, being successful in my role is helping others succeed, but also that’s very different from pushing code to production once a day. In many cases the results take much longer, especially when you work at the organizational level; initiatives take a long time, things I work on may never actually come true. So finding ways to feel successful and to get a sense of accomplishment, especially when you’ve moved from an engineer role into management, is really important.

I have, in the past with people who I’ve coached with, I’ve basically pursued two angles. One is basically just being conscious of that happening and understanding that it’s a common feeling in such a career transition, but also setting clear goals and expectations, both for your own work and for the people who are reporting to you. And then it’s also about connecting with what motivated you to move into a management role — what are the things that made it attractive for you, and how can you get more of that?

The other main thing for such a transition is just always making sure you’re very clear on expectations and goals. You have to know what’s expected and what the business goals are, as well as be clear with people who reporting to you. So much of management going wrong is just expectations that are going sideways, and that can usually more easily be prevented than fixed afterwards.

For more of Lena’s advice for the next generation, visit the Codecademy blog.

One critical engineering metric can help you innovate faster, outrun your competition, and retain top talent: Cycle Time. It’s your team’s speedometer, and it’s the key to everything from developer satisfaction to predictable sprints. And Cycle Time has implications beyond engineering — it’s also an important indicator of business success.

That’s why we’re excited to announce the release of our new book, The Engineering Leader’s Guide to Cycle Time. For those looking to boost their team’s efficiency and productivity, we offer a data-driven approach, backed by research, case studies, and our own experience as an industry-leading Engineering Intelligence platform.

The book dives into the components of this critical metric, breaking down the development pipeline into distinct stages to highlight common bottlenecks and opportunities for acceleration. The foreword, by Edith Harbaugh, CEO and Co-Founder of LaunchDarkly, places Cycle Time in context, explaining how it’s integral to the latest shift in software development methodology — the shift towards CI/CD.

Download it now (it’s free!) for a breakdown of the most important engineering metrics, strategic advice on increasing engineering speed, and real-world advice from senior engineering leaders.

For our new series, 1:1 with Engineering Leaders, Code Climate and Codecademy for Business spoke to managers and VPs about their career journey, leadership strategies, and advice for the next generation of engineers. Below is an excerpt from our conversation with Gergely Nemeth, Group Engineering Manager at Intuit, who shared his thoughts on the role of a manager, and the challenges of joining a remote team. Edited for length and clarity.

For Gergely’s advice for early-career engineers, visit the Codecademy blog.

Tell us a bit about your current role and how you got there.

I just started a new role at Intuit, and I’m leading some parts of the Financial Data Platform on the experience side of things. For example, if you’re using Mint, TurboTax, or QuickBooks, I’m on the team that’s responsible for connecting your bank accounts or other financial institutions to those Intuit products.

Prior to joining Intuit, I worked at Uber, where I, too, was working on the design side of things. I built the design systems engineering team there, which works mostly on open source projects like Base Web or Styletron. Before that, I worked at a company called RisingStack, which I co-founded. That’s how I got into management.

Could you talk a bit more about your transition from individual contributor to manager? Did you always know that you wanted to be a manager or was it something that transpired?

I always wanted to give it a try, mostly because I really enjoy helping others grow, supporting them. The way I got into management was with RisingStack, the company I co-founded. We were looking for someone who would start managing the engineering team — I always wanted to try that role, so we agreed that I would take on that responsibility.

What do you believe is the role of a manager on an engineering team and how about the role of a leader? Is there a difference in your opinion?

In my opinion, leadership is a necessary management skill — it’s part of being a manager.

One of the most important things from a manager’s point of view is to make sure that the team has a vision, and knows why it exists in the first place, what it wants to achieve. The manager should provide clarity.

Then, the manager should help engineers on the team grow, making sure that they can progress in their careers. Another really important thing is to ensure that team members can build connections within the company, and make sure that they can work well with other business functions, whether it’s legal, finance, or design.

It’s also important for an EM to help build the company’s technical brand. Maybe it’s the open-source contributor in me that thinks this, but if engineers on the team can write a blog post, can contribute to open source, that will help grow the company’s tech brand and through that, it will make hiring a lot easier. It also gives back to the open-source projects that we rely on every day, so it’s also about being a good open-source citizen.

You said that you recently started a new role at Intuit — could you speak to your strategies for joining a new team and learning about its particular challenges?

It was definitely challenging, especially because of COVID and how I had to onboard through Zoom and Slack. I had never done this before. In this new virtual world of ours, lots of clues like body language are missing. Small things like this make onboarding in this new environment a lot more challenging.

The only way to make up for it is to make it a priority to meet with everyone more, especially in the first few weeks. In my first few weeks, I felt like I was in meetings all day, every day because the team I am responsible for is relatively large. Also, we have lots of stakeholders that I had to meet with too.

I had to make sure that I built that network that I previously talked about. It’s a lot of time investment in meetings, making sure you meet with everyone.

The way I structured my onboarding was that I wanted to make sure that I had a good working relationship with the team first. I think it’s super important that I do weekly 1 on 1s, especially when I join a new team. Through that, I get to know the person more and also the team, too. I started my 1 on 1s in a way that focused on the team’s challenges, both from a technical point of view, as well as from a process or communication point of view. That helped me onboard more quickly in the sense that I understood the problems each person faced a lot quicker than just trying to observe them.

At the same time, observation was really a key part, too. So in the first month, I made sure not to make any big decisions, just listening in meetings, understanding team dynamics, and learning the product itself.

After the fourth week was when I really started to grasp the entire scope of the team.

That’s actually a perfect segue into the next question — what do you think managers need to do differently when they’re managing a fully remote team? Are there any remote-specific strategies you used?

Yeah, I think there are a few things. First, it’s especially important these days to over-communicate to make sure everyone has the necessary context. There are no such things as hallway conversations anymore, or having team lunches together where we could discuss things related to work if needed. We have to make sure that everyone is aware of everything, even if it means over-communicating every once in a while.

Another challenging aspect during these times is that lots of team members have their family at home with them, or they don’t have the perfect work from home environment, myself included.

Because of this, it’s extremely important that teams and managers are accommodating — not everyone will be able to join all the meetings, and sometimes kids will show up in Zoom calls. And it’s perfectly fine, it’s a good opportunity to say hi. So to sum up, we should be as flexible and accommodating as possible.

Do you use metrics or data at all in your day to day, and if so, why?

We mostly focus on business-related outcome metrics. It gives us an understanding of whether we are moving the needle in the right direction. For example, making sure that the feature we are implementing moves us in the right direction from a customer point of view.

Intuit is a customer-obsessed company. For us, it’s really important that we are always working on the most important things for our customers. All of the metrics we are tracking for our team, are to make sure that the customer is successful in, for example, running their own small business, or reaching their personal financial goals.

Previously, I managed the developer velocity team at Uber. The reason I’m mentioning it is because I know that Code Climate is more similar to that from a metric point of view. We tracked a few metrics around how quickly a pull request gets reviewed, for example. This gives front-line managers a high-level overview of team health.

For more of Gergely’s advice for the next generation, visit the Codecademy blog.

For our ongoing series, 1:1 with Engineering Leaders, Code Climate and Codecademy for Business spoke to managers and VPs about their career journey, leadership strategies, and advice for the next generation of engineers. Below is an excerpt from our conversation with Brooks Swinnerton, Senior Engineering Manager at Github, who shared the value of hackathons, the importance of getting to know your team members, and the most interesting management advice he’s received. Edited for length and clarity.

For Brooks’s advice for early-career engineers, visit the Codecademy blog.

Tell us about your current role. What are your current responsibilities, and how did you get there?

I’m an Engineering Manager at GitHub, where I work on a team called Ecosystem Events. And what we do is we manage the infrastructure that powers webhooks. Webhooks are kind of the inverse of an API, where an event happens on github.com — like someone opens up an issue or a pull request — and we send an HTTP request out to people that are interested in knowing. And that powers things like various parts of Code Climate, for example.

I’ve been at GitHub for about five years now. I first started out as an individual contributor on our API team. Previously, I worked at a company called General Assembly building out kind of a backend coding platform for our mobile app. And prior to that, I worked at NYU as a Systems Administrator. I’ve been in the tech scene for a little while, though software engineering specifically wasn’t something that I really got started with until I started at General Assembly.

Fast forward about three and a half years through my career at GitHub, and one of my teammates went off and spun off her own team, a one-person team to focus on this area that we now focus on. I found that particular area really interesting and I jumped ship to join her. It became pretty clear shortly after that we needed an Engineering Manager. We needed someone to articulate the problems that we were trying to solve, to the product organization and to leadership. I was given the opportunity to try out engineering management, and here I am.

Let’s start with what made you decide to get into engineering, because that wasn’t where your career started.

The beginning came from hackathons. A while ago, I actually got on a hackathon-on-wheels known as the StartupBus, where you get on this bus with a bunch of people that you don’t know. And the idea is you build a startup on your way to the South by Southwest festival in Texas.

That my first realization that, “Oh my gosh, coding is really cool.” I had done coding before, but not building web applications or anything like that. We got on a bus and coded our own startup on the way to South by Southwest. And right after that, I took a class at General Assembly known as Intro to Rails, where I learned Ruby on Rails.

I realized that I am very interested in being able to create something from nothing.

Was that bus something you had to apply for?

It was something you had to apply to. I heard about it at the New York Tech Meetup, which was this very big technical Meetup at NYU in Manhattan. I never thought I’d get in because I didn’t have any experience in coding. And met a ton of really valuable people and it was, more than anything, an amazing networking experience.

Hackathons in general are a really fascinating way to meet people.

Let’s jump forward to your next major transition, from IC to manager. Was that a leap you expected to make? Did you know you wanted to be a manager?

Yeah. It was something that I wanted to do early on. There was a sense of autonomy that I was looking for. And thinking back to the role when I started at GitHub as an Engineering Manager, it was largely a gap that I was trying to fill for our particular team. I thought that the most value that I could provide to the company was in this new role of Engineering Manager, rather than writing the code.

People often move into management because they think that it’s the next most logical step in their career progression. But what most folks who make that transition realize is that you’re really starting over. You go from being a software engineer who may or may not be pretty comfortable with like your area of expertise, to a completely different world.

I had the opportunity to move into this because the previous Engineering Manager left to move to another team and there was a gap that needed to be filled. But by communicating with that old manager, I was able to find out how to best move forward on the path to engineering management.

And did that person have any particularly good advice?

Yeah. I had to interview for the role, and I talked a lot to folks who were around me in this particular organization. Some of the most interesting advice that I got was more of a heads up that engineering management has really high highs and really low lows.

It’s really amazing that you can motivate other people and empower them to ship the most interesting things that they’ve shipped in their careers. But there are also some really tough conversations that you need to have over time as well.

How do you think the role of a manager differs from the role of a leader? Is there a difference?

I think there are fewer dissimilarities than people think. You can certainly be a leader as an IC, or as an Engineering Manager. In terms of communication, for example, delivering feedback is a really concrete way of trying to better someone on your team, and that doesn’t necessarily have to come from an Engineering Manager.

It seems like you were kind of touching on that a little bit before when you were saying, “If you want to be a manager, try to influence others and start stepping up.”

Definitely. I’ve seen a lot of really incredible people in my career at GitHub who are able to influence not just their own technical project, but the way that their team works, for example. And that’s something that really can help improve the productivity of the entire team.

You have some writing out there — some blog posts, some talks — it’s all very technical. And I know a lot of the time it’s tough for people who are thinking about moving into management to contemplate letting go of the technical side of things. How do you balance that?

That’s a fantastic question. It’s a struggle. I do try and stay technical, whether that’s on the weekends or just in my own personal time. But I recognize that not everyone has the opportunity to do that. And that’s something that ideally you could set aside time for in your day-to-day role.

For example, at GitHub, we have this concept of a Day of Learning. It’s your opportunity to brush up your skills, and you can use that however you see fit. As an Engineering Manager, you may be interested attending a conference or something like that. As an IC, you may be interested in learning a new programming language.

For me personally, what I’ve been trying to do is brush up on both.

Is GitHub usually co-located, remote, or partially distributed?

All of the above. I was looking at the numbers not too long ago. I think pre-COVID we were a large majority remote as a company.

My entire team at GitHub is remote. We have one person who goes into the office, but that effectively makes him remote whenever we’re all talking to one another. The spread on my team goes from San Francisco on the West Coast in one time zone boundary to London, England on the other. It makes for some interesting challenges and trying to schedule meetings and things like that.

Other than the obvious logistical challenges, what challenges does remote leadership present for a manager?

My default is to try and have a face-to-face communication. And we set aside time to do 1 on 1s. I do 1 on 1 with everyone on my team, and that’s pretty common practice at GitHub.

The meeting scheduling is challenging, but I think what GitHub does really well for remote work is optimizing for asynchronous communication. Whether that’s in Slack, whether that’s a GitHub issue. We use GitHub to build GitHub to an extreme — everything is documented in a GitHub repository.

We have team repositories, which represent the composition of the team that was on it, with each of their time zones, documentation on the way that we like to work, the way that we like to review pull requests. We have issues for every project that we’re working on. And what’s fascinating about working like that for an extended period of time is that you can go back throughout the entire history of GitHub and see why every decision was made and what everyone was doing at that moment in time.

That is a really fantastic side effect of asynchronous communication. It does make things challenging if you want to search through, but if you look hard enough, usually you can find the answer to any questions that you have, which is awesome.

How do you get to know your team and help them grow professionally — individually and together?

It’s a challenge as a remote employee, I think. The thing that I miss the most about being in-person at General Assembly is just that human-to-human interaction. It’s not to say that you can’t read the body language over video, but it’s just a little bit different.

1 on 1s are the primary way to talk about career progression and feedback and just kind of whatever’s on that person’s mind that week.

In addition to that, pre-COVID, what we would do is get everyone together for what we call mini summits. They were a way for us to come together, usually around a pretty tactical goal. During those there are lots of team-building opportunities and opportunities to get to know one another outside of a work setting, which is really beneficial for having a well-formed team dynamic. It’s definitely much trickier now.

What advice do you have for new managers or people looking to become managers?

I think everyone’s path is a little bit different to becoming a manager and also getting in the flow of being a manager. As someone goes from an IC to a manager, especially if you’re working with the same people, that can pose some really unique interpersonal challenges. That’s something to approach with a bit of caution, and just acknowledge the fact that’s happening.

In addition to that, I found that having a leadership coach has been incredibly useful just to have a sounding board. It’s nice to have someone to talk to who has no context of the company that you work at or the specific people that you’re talking about. I found that to be really beneficial. If you have a learning stipend or anything like that at your company, that’s a really fantastic way to use it.

I took what I believed to be a really pragmatic approach of reading as many management books as I could. And while those are valuable for learning those techniques, I’ve found that every distinct human relationship that you have on the team is a little bit different. Understanding that style and getting to know each person is step one in being an effective engineering leader.

Any last comments or thoughts?

We talked a bit about software engineering as this really interesting problem-solving experience. Sometimes that may not come to you in the period from of 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM. And especially in the time that we’re going through right now, you may able to work different hours. That creativity may come to you outside the bounds of a normal working day.

Try to optimize for that. and try and optimize your team for that, I think more specifically. If you can do asynchronous communication, now’s the time to try and take advantage of that so that you can optimize for whatever works best for you. It’s a little tricky at times, and you have to be able to pass off work. Make sure you’re very explicit about how you pass off that work. That’s kind of the key to being able to work whenever you’d like, which unlocks a lot of really awesome possibilities outside of the day to day.

How do you make sure you’re really optimizing for the way your mind works, and not just procrastinating?

It’s a really good point. I think to an extent there’s some trust that you need to have. And that’s also one of the things about being a leader — making sure that you can follow up and have real conversations of like, “Hey, how’s that project coming along right now?” Building that team communication to keep people motivated and interested and continuously communicating, I think is the key to success there.

For more of Brooks’s advice for the next generation, visit the Codecademy blog.

For our new series, 1:1 with Engineering Leaders, Code Climate and Codecademy for Business spoke to managers and VPs about their career journey, leadership strategies, and advice for the next generation of engineers. Below is an excerpt from our conversation with Tara Ellis, Manager, UI Engineering at Netflix, who discussed her strategies for building trust on an engineering team. Edited for length and clarity.

For Tara’s advice for early-career engineers, visit the Codecademy blog.

Tell us about your current role, and how you got there.

I currently lead a team of engineers in the growth space, and I work specifically on payments. As I like to tell people, we are the money of Netflix.

I manage a UI team. How did I get here? I actually I had never worked in growth before, even though I had been managing UI teams before. But the Director in my current role is someone I had worked with before in my prior job, and he had spent a lot of time trying to get me to come to Netflix. Eventually I decided that it sounded like an awesome challenge, and I wanted to try it out. I took the plunge.

But it took many, many years of doing lots of different things to get here. I’ve been in this role for four years, but I am moving from the product side over to the studio organization at Netflix. I’m working on a new initiative, and I basically have the opportunity to build out a whole new team that’s going to be a part of a whole new organization. I’m super excited about it, because how often do you get the opportunity to have a start up experience while still in the safety of a company?

Can you tell me a little bit about your transition from IC to manager? Did you always know you wanted to be a manager?

Absolutely not. I actually was someone who was pretty hostile to management for large portions of my career. I think if there are a lot of not-great managers in the room, I think sometimes it gives it a bad rep. I actually think management and leadership are really awesome things to do.

So no, I did not want to be a manager. I wanted to basically go as far as I possibly could technically, because I was a grade-A nerd, and I really loved the intricacies of the craft. But eventually after a number of years, I came to this realization that I had solved all of the problems that I was interested in solving, I mean certainly not all of CS’s problems, but all of the ones I wanted to solve. My day to day became taking things out of the database and putting things into the database, and it didn’t matter what platform, what language.

At that point, people started to become really interesting to me. I got a little taste of that when I was a tech lead. If you can do technical leadership first before moving into a people manager role, it’s a great path, because it’ll allow you to get a sliver of that job and decide if you like it, and then keep getting into the harder part of the job, which is the people. I really enjoy growing, and leading people. I would not have thought that 10 years ago, but now I think it’s amazing.

It sounds like a little bit of your fear — in addition to not having great experiences with certain managers — was leaving the technical side of things.

Yeah. A lot of engineers don’t really understand what managers do, and I was absolutely one of them. So it feels like, “Oh, you don’t produce a thing, right? You sit in a meeting, and then you tell me what to do.” Because I had this very narrow conception of what that role was, it felt certainly less noble than being the one making the thing. I’ve since learned that both jobs are awesome, and even though I’m not hands-on making the thing, I make it possible for the makers to make the thing. That became far more compelling. I do still code though because I’m a nerd. I just don’t code professionally.

So you code on the side, as a passion project?

Yeah, I just love learning new things. I’ve been going back and forth on my multi year quest to decide if I want to learn Android development. I have a good friend who builds mobile games, and keeps trying to get me to do a few screens for him as a learning exercise. So now it’s more about finding the time. But I’ve traditionally been a front-end engineer, so I think mobile is an interesting space from the perspective of, “Oh you can control everything,” as opposed to the web where it’s not that simple.

It’s great that you’re able to pursue your passion on the side. To broaden out a little bit, now that you’ve been a manager, what do you see as the role of a manager on an engineering team?

I will say I definitely think there’s some overlapping duties, but it does depend on the company. So in my prior role as a manager before coming to Netflix, I did a lot more technical leadership. The engineering team itself was a variety of backgrounds, from interns all the way to the super senior people. Because I had junior engineers, I spent a little more time in the weeds than I do at Netflix. In that role, and that job, my role was to deal with resourcing, deal with planning, deal with technical leadership, that kind of stuff.

I was so in the weeds that when I actually came to Netflix, my first four months I was like, “What is my job?” I would argue that this is much more of a leadership role than a manager role, because it’s a little less tactical.

With my team, my job is to lead them, inspire them, motivate them, help them grow their careers, push them in the ways that will make them more well-rounded developers. If I’m doing my job right, then they will eventually leave, because they’ve grown.

So how did you discover who you were as a leader?

I’m still trying to figure that out. It’s been an ongoing multi-year, perhaps multi-decade process, because my career has morphed. A lot of it has come down to having different experiences and really trying to evaluate what they mean, and how I’m motivated. A through line for me is that I really care a lot about performance. Towards the end of my coding career, a lot of my specialty was squeezing milliseconds out of things, and I think that hasn’t changed. I’m just now doing it with people — how do we become the most efficient, well-performing team.

I had to really introspect and figure out over a lifetime of work of who am I and what do I value, what do I bring to the table, and how do I serve the people that I work for? I said it’s shifted, because my roles were very different. It’s funny, when I became a manager, the joke is that I became so nice. Not that I wasn’t nice before, but the job now is about motivation.

So when you figured that out, you said you value performance, for example, how does that impact your day to day work as a leader and a manager? How do you help people boost their performance?

I have the fortune of working in a place where most of the engineers already come with that mindset. But as a general rule, it has been my experience that people respond really well to expectations. They just want to know what is required of them. They want to know how they’re doing. One of the first things I do is to lay out, “This is what it means to be succeeding. This is what I’m looking for.”

I say “These are my expectations, and my assumption is you’re going to be able to live up to this. If you can’t, let’s talk about it.” It’s not, “Hey I have this expectation. You haven’t hit the bar. Goodbye.”

One thing we talk a lot about at Code Climate is how it can be hard for managers to have visibility into the work that’s getting done. That visibility is important not just in getting the product to market, but it’s also important in the kinds of conversations that you’re having. How do you get enough insight into what’s happening on the team and on an individual level to have that conversation?

I’m a big talker, as you may have noticed. I’m also a big fan of multivalent points of view. I talk to an engineer individually, and I talk to the people around them. I’m lucky that I work in a culture where it’s normal for people to talk about how other engineers are doing, and to give managers public feedback. So for example, an engineer emailed another engineer and his boss and me to say how great he had done on this project, and exactly what he had done that was really great. I just got that unsolicited, so that helps.

If it feels like something is going on, you have to be really careful about that, because nobody wants to feel like they’re snitching on someone. It’s really about setting the context of, “Look, he’s not in trouble. I just want to make sure that everything’s okay” and then also asking really transparent, candid questions.

You’ve got to really want to know the answer, and sometimes you have to ask multiple times, multiple different ways in the same conversation to get someone to tell you the truth. It doesn’t always feel safe to tell you the truth. They don’t know what you’re going to do with it. So you have to do the work to build up rapport before you get into deep conversations. High level I think it’s a curiosity. It’s a genuine non-transactional curiosity. When people know that you care about them, they’ll be more responsive. I’m not trying to find this out because I’m trying to fire you. I’m trying to find this out because I want to help you.

How do you build that trust and safety on your team?

I really try to build a strong sense of loyalty between the devs themselves, irrespective of me. I’d rather you be loyal to each other than me, because then you will work really hard for each other. You won’t want to let each other down.

Then with myself, I feel the best when I feel like someone is telling me the truth. When they’re not telling me what I want to hear, and when they’re comfortable being vulnerable. So I try to mirror that back with my devs. I’m a firm believer in the 1 on 1. It’s their time, it’s not my time. As I like to say when I’m setting those up for the first time, “I don’t want to talk about your project. I have 14,000 other ways to learn about your project, but I only have this one 30 minute block to talk to you.” I want to spend that time building trust, getting to know each other.

Maybe for the first one on one, people are a little taken aback by how direct I’ve been. They’re like, “Okay cool.” Then the next meeting they’ll come in and they’ll start giving me a rundown of their projects. I stop them and say, “Nope, we’re not doing that. What’d you do this weekend?”

It takes a while. But eventually, we start having real conversations.

How does your strategy for building safety and transparency differ when you’re coming into an existing team with an existing dynamic, and creating a new team?