Sasha Rezvina

Service-Oriented Architecture has a well-deserved reputation amongst Ruby and Rails developers as a solid approach to easing painful growth by extracting concerns from large applications. These new, smaller services typically still use Rails or Sinatra, and use JSON to communicate over HTTP. Though JSON has many obvious advantages as a data interchange format – it is human readable, well understood, and typically performs well – it also has its issues.

Where browsers and JavaScript are not consuming the data directly – particularly in the case of internal services – it’s my opinion that structured formats, such as Google’s Protocol Buffers, are a better choice than JSON for encoding data. If you’ve never seen Protocol Buffers before, you can check out some more information here, but don’t worry – I’ll give you a brief introduction to using them in Ruby before listing the reasons why you should consider choosing Protocol Buffers over JSON for your next service.

A Brief Introduction to Protocol Buffers

First of all, what are Protocol Buffers? The docs say:

“Protocol Buffers are a way of encoding structured data in an efficient yet extensible format.”

Google developed Protocol Buffers for use in their internal services. It is a binary encoding format that allows you to specify a schema for your data using a specification language, like so:

message Person { required int32 id = 1; required string name = 2; optional string email = 3; }

You can package messages within namespaces or declare them at the top level as above. The snippet defines the schema for a Person data type that has three fields: id, name, and email. In addition to naming a field, you can provide a type that will determine how the data is encoded and sent over the wire – above we see an int32 type and a string type. Keywords for validation and structure are also provided (required and optional above), and fields are numbered, which aids in backward compatibility, which I’ll cover in more detail below.

The Protocol Buffers specification is implemented in various languages: Java, C, Go, etc. are all supported, and most modern languages have an implementation if you look around. Ruby is no exception and there are a few different Gems that can be used to encode and decode data using Protocol Buffers. What this means is that one spec can be used to transfer data between systems regardless of their implementation language.

For example, installing the ruby-protocol-buffers Ruby Gem installs a binary called ruby-protoc that can be used in combination with the main Protocol Buffers library (brew install protobuf on OSX) to automatically generate stub class files that are used to encode and decode your data for you. Running the binary against the proto file above yields the following Ruby class:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby # Generated by the protocol buffer compiler. DO NOT EDIT! require 'protocol_buffers' # forward declarations class Person < ::ProtocolBuffers::Message; end class Person < ::ProtocolBuffers::Message set_fully_qualified_name "Person" required :int32, :id, 1 required :string, :name, 2 optional :string, :email, 3 end

As you can see, by providing a schema, we now automatically get a class that can be used to encode and decode messages into Protocol Buffer format (inspect the code of the ProtocolBuffers::Message base class in the Gem for more details). Now that we’ve seen a bit of an overview, let’s dive in to the specifics a bit more as I try to convince you to consider taking a look at Protocol Buffers – here are five reasons to start.

Reason #1: Schemas Are Awesome

There is a certain painful irony to the fact that we carefully craft our data models inside our databases, maintain layers of code to keep these data models in check, and then allow all of that forethought to fly out the window when we want to send that data over the wire to another service. All too often we rely on inconsistent code at the boundaries between our systems that don’t enforce the structural components of our data that are so important. Encoding the semantics of your business objects once, in proto format, is enough to help ensure that the signal doesn’t get lost between applications, and that the boundaries you create enforce your business rules.

Reason #2: Backward Compatibility For Free

Numbered fields in proto definitions obviate the need for version checks which is one of the explicitly stated motivations for the design and implementation of Protocol Buffers. As the developer documentation states, the protocol was designed in part to avoid “ugly code” like this for checking protocol versions:

if (version == 3) { ... } else if (version > 4) { if (version == 5) { ... } ... }

With numbered fields, you never have to change the behavior of code going forward to maintain backward compatibility with older versions. As the documentation states, once Protocol Buffers were introduced:

“New fields could be easily introduced, and intermediate servers that didn’t need to inspect the data could simply parse it and pass through the data without needing to know about all the fields.”

Having deployed multiple JSON services that have suffered from problems relating to evolving schemas and backward compatibility, I am now a big believer in how numbered fields can prevent errors and make rolling out new features and services simpler.

Reason #3: Less Boilerplate Code

In addition to explicit version checks and the lack of backward compatibility, JSON endpoints in HTTP-based services typically rely on hand-written ad-hoc boilerplate code to handle the encoding and decoding of Ruby objects to and from JSON. Parser and Presenter classes often contain hidden business logic and expose the fragile nature of hand parsing each new data type when a stub class as generated by Protocol Buffers (that you generally never have to touch) can provide much of the same functionality without all of the headaches. As your schema evolves so too will your proto generated classes (once you regenerate them, admittedly), leaving more room for you to focus on the challenges of keeping your application going and building your product.

Reason #4: Validations and Extensibility

The required, optional, and repeated keywords in Protocol Buffers definitions are extremely powerful. They allow you to encode, at the schema level, the shape of your data structure, and the implementation details of how classes work in each language are handled for you. The Ruby protocol_buffers library will raise exceptions, for example, if you try to encode an object instance which does not have the required fields filled in. You can also always change a field from being required to being optional or vice-versa by simply rolling to a new numbered field for that value. Having this kind of flexibility encoded into the semantics of the serialization format is incredibly powerful.

Since you can also embed proto definitions inside others, you can also have generic Request and Response structures which allow for the transport of other data structures over the wire, creating an opportunity for truly flexible and safe data transfer between services. Database systems like Riak use protocol buffers to great effect – I recommend checking out their interface for some inspiration.

Reason #5: Easy Language Interoperability

Because Protocol Buffers are implemented in a variety of languages, they make interoperability between polyglot applications in your architecture that much simpler. If you’re introducing a new service with one in Java or Go, or even communicating with a backend written in Node, or Clojure, or Scala, you simply have to hand the proto file to the code generator written in the target language and you have some nice guarantees about the safety and interoperability between those architectures. The finer points of platform specific data types should be handled for you in the target language implementation, and you can get back to focusing on the hard parts of your problem instead of matching up fields and data types in your ad hoc JSON encoding and decoding schemes.

When Is JSON A Better Fit?

There do remain times when JSON is a better fit than something like Protocol Buffers, including situations where:

- You need or want data to be human readable

- Data from the service is directly consumed by a web browser

- Your server side application is written in JavaScript

- You aren’t prepared to tie the data model to a schema

- You don’t have the bandwidth to add another tool to your arsenal

- The operational burden of running a different kind of network service is too great

And probably lots more. In the end, as always, it’s very important to keep tradeoffs in mind and blindly choosing one technology over another won’t get you anywhere.

Conclusion

Protocol Buffers offer several compelling advantages over JSON for sending data over the wire between internal services. While not a wholesale replacement for JSON, especially for services which are directly consumed by a web browser, Protocol Buffers offers very real advantages not only in the ways outlined above, but also typically in terms of speed of encoding and decoding, size of the data on the wire, and more.

There are a few common questions that we get when speaking with Code Climate Quality customers. They range from “What’s the Code Climate score for the Code Climate repo?” to “What’s the average GPA of a Rails application?” When I think back on the dozens of conversations I’ve had about Code Climate, one thing is clear – people are interested in our data!

Toward that end, this is the first post in a series intended to explore Code Climate’s data set in ways that can deepen our understanding of software engineering, and hopefully quench some people’s curiosities as well. We have lots of questions to ask of our data set, and we know that our users have lots of their own, but we wanted to start with one that’s fundamental to Code Climate’s mission, and that we’re asked a lot:

Does Team Size Impact Code Quality?

Is it true that more developers means more complexity? Is there an ideal number of developers for a team? What can we learn from this? Let’s find out!

The Methodology

There are a variety of different ways that this question can be interpreted, even through the lens of our data set. Since this is the first post in a series, and we’re easing into this whole “data science” thing, I decided to start with something pretty straightforward – plotting author count against Code Climate’s calculated GPA for a repo.

Author count is calculated by summing the authors present in commits over a given period, in this case 30 days. The GPA is calculated by looking up the most recent quality report for a repo and using the GPA found there. Querying this data amounted to a few simple lines of Ruby code to extract from our database, including exporting the data as a CSV for processing elsewhere.

I decided to limit the query to our private repositories because the business impact of the answer to the question at hand seems potentially significant. By analyzing private repositories we will be able to see many more Rails applications than are available in Open Source, and additionally, the questions around Open Source repos are manifold and deserve to be treated separately.

Please note that the data I’m presenting is completely anonymized and amounts to aggregate data from which no private information can be extrapolated.

Once I had the information in an easily digestible CSV format, I began to plot the data in a program called Wizard, which makes statistical exploration dead simple. I was able to confirm that there was a negative correlation between the size of a team and the Code Climate GPA, but the graph it produces isn’t customizable enough to display here. From there I went to R, where a few R wizard friends of mine helped me tune a few lines of code that transform the CSV a graph.

The fit line above indicates that there is indeed an indirect relationship between code quality and team size. While not a very steep curve, the line shows that a decline of over 1 GPA point is possible when team sizes grow beyond a certain point; let’s dig a little deeper into this data.

The graph is based on data from 10,000 observations, where each is a distinct repo and the GPA measurement and author count measurements are the latest available. The statistical distributions of the two columns show that the data needed some filtering. For example, the GPA summary seems quite reasonable:

> summary(observations$GPA) Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. 0.000 2.320 3.170 2.898 3.800 4.000

As you would expect, a pretty healthy distribution of GPAs. The author count, on the other hand, is pretty out of whack:

> summary(observations$AuthorCount) Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. 1.000 1.000 2.000 3.856 4.000 130.000

The 3rd Quantile ranges 4-130! That’s way too big of a spread, so I’ve corrected for that a bit by filtering the max to 50 in the graph above. This gives enough of a trend to show how new teams may tend to fall according to the model, but doesn’t completely blow it out with outliers. After working on this graph with the full data set and showing it to a couple people, some themes emerged:

- The data should be binned, with 10+ authors being the largest team size

- Lines or bars could be used to show the “density” of GPAs for a specific binned team size

Some CSV and SQL magic made it pretty straightforward to bin the data, which can then be plotted in R using a geometric density function applied to team sizes per GPA score. This lets us see areas of concentration of GPA scores per team size bin.

Now that the team sizes are broken up into smaller segments, we can see some patterns emerge. It appears easier to achieve a 4.0 GPA if you are a solo developerand additionally, the density of teams greater than 10 concentrates under the 3.0 GPA mark. This is a much richer way to look at the data than the scatterplot above and I learned a lot comparing the two approaches.

Nice first impressions, but now that we’ve seen the graphs, what can we learn?

Conclusions

How to interpret the results of this query is quite tricky. On one hand, there does appear to be a correlation supporting the notion that smaller teams can produce more organized code. On the other hand, the strength of this correlation is not extreme, and it is worth noting that teams of up to 10, 20, and 30 members are capable of maintaining very respectable GPAs which are greater than 3.0 (recall from the summary above that the mean GPA is 2.898 and that only the top 25% score greater than 3.8).

The scatterplot graph shows a weak fit line which suggests a negative correlation, while the density line graph (which could also be rendered with bars) shows that teams of up to 10 members have an easier time maintaining a 3.0+ GPA than teams with more than 10 members. Very intriguing.

It is worth considering what other factors could be brought into play when it comes to this model. Some obvious contenders include the size of the code base, the age of the code base, and the number of commits in a given period. It’s also worth looking into how this data would change if all of the historical data was pulled up, to sum the total number of authors over the life of a project.

One conclusion to draw might be that recent arguments for breaking down large teams into smaller, service oriented teams may have some statistical backing. If we wanted to be as scientific about it as possible, we can look at how productive teams tend to be in certain size ranges and produce an ideal team size as a function of productivity and 75% percentile quality scores. Teams can be optimized to produce a certain amount of code of a certain quality for a certain price – but now we’re sounding a little creepy.

My take is that this data supports what most developers already know – that large teams with large projects are hard to keep clean; that’s why we work as hard as we do. If you’re nearing that 10-person limit, know that you’ll have to work extra hard to beat the odds and have a higher than 3.0 GPA.

On a parting note, we are sure that there are more sophisticated statistical analyses that could be brought to bear on this data, which is why we have decided to publish the data set and the code for this blog post here. Check it out and let us know if you do anything cool with it!

Special thanks to Allen Goodman (@goodmanio), JD Maturen (@jdmaturen), and Leif Walsh (@leifw) for their code and help and to Julia Evans (@b0rk) for the inspiration.

Ruby developers often wax enthusiastic about the speed and agility with which they are able to write programs, and have relied on two techniques more than any other to support this: tests and documentation.

After spending some time looking into other languages and language communities, it’s my belief that as Ruby developers, we are missing out on a third crucial tool that can extend our design capabilities, giving us richer tools with which to reason about our programs. This tool is a rich type system.

To be clear, I am in no way saying that tests and documentation do not have value, nor am I saying that the addition of a modern type system to Ruby is necessary for a certain class of applications to succeed – the number of successful businesses started with Ruby and Rails is proof enough. Rather, I am saying that a richer type system with a well designed type-checker could give our design several advantages that are hard to accomplish with tests and documentation alone:

- Truly executable documentation

Types declared for methods or fields are enforced by the type checker. Annotated classes are easy to parse by developers and documentation can be extracted from type annotations. - Stable specification

Tests which assert the input and return values of methods are brittle, raise confusing errors, and bloat test suites; documentation gets out of sync. Type annotations change with your implementation and can help maintain interface stability. - Meaningful error messages

Type checkers are valuable in part because they bridge the gap between the code and the meaning of a program. Error messages which inform you not only that you made a mistake, but how (and potentially how to fix it) are possible with the right tools. - Type driven design

Considering the design of a module of a program through its types can be an interesting exercise. With advancements in type checking and inference for dynamic programming languages, it may be possible to rely on these tools to help guide our program design.

Integrating traditional typing into a dynamic language like Ruby is inherently challenging. However, in searching for a way to integrate these design advantages into Ruby programs, I have come across a very interesting body of research about “gradual typing” systems. These systems exist to include, typically on a library level, the kinds of type checking and inference functionality that would allow Ruby developers to benefit from typing without the expected overhead. [1]

In doing this research I was pleasantly surprised to find that four researchers from the University of Maryland’s Department of Computer Science have designed such a system for Ruby, and have published a paper summarizing their work. It is presented as “The Ruby Type Checker” which they describe as “…a tool that adds type checking to Ruby, an object-oriented, dynamic scripting language.” [2] Awesome, let’s take a look at it!

The Ruby Type Checker

The implementation of the Ruby Type Checker (rtc) is described by the authors as “a Ruby library in which all type checking occurs at run time; thus it checks types later than a purely static system, but earlier than a traditional dynamic type system.” So right away we see that this tool isn’t meant to change the principal means of development relied on by Ruby developers, but rather to augment it. This is similar to how we think about Code Climate – as a tool which brings information about problems in your code earlier in your process.

What else can it do? A little more from the abstract:

“Rtc supports type annotations on classes, methods, and objects and rtc provides a rich type language that includes union and intersection types, higher- order (block) types, and parametric polymorphism among other features.”

Awesome. Reading a bit more into the paper we see that rtc operates by two main mechanisms:

- Compiling field and method annotations to a data structure that is later used for checks

- Optionally proxying calls through a system that gathers type information, allowing type errors to be raised on method entry and exit

So now let’s see how these mechanisms might be used in practice. We’ll walk through the ways that you can annotate the type of a class’s fields, and show what method type declarations look like.

First, field annotations on a class look like this:

class Foo typesig('@title: String') attr_accessor :title end

And method annotations should look familiar to you if you’ve seen type declarations for methods in other languages:

class Foo typesig("self.build: (Hash) -> Post") def self.build(attrs) # ... method definition end end

Where the input type appears in parens, and then the return type appears after the -> arrow that represents function application.

Similar to the work in typed Clojure and typed Racket (two of the more well-developed ‘gradual’ type systems), rtc is available as a library and can be used or not used a la carte. This flexibility is fantastic for Ruby developers. It means that we can isolate parts of our programs which might be amenable to type-driven design, and selectively apply the kinds of run time guarantees that type systems can give us, without having to go whole hog. Again, we don’t have to change the entire way we work, but we might augment our tools with just a little bit more.

How Would We Use Gradual Typing?

Asking the following question on Twitter got me A LOT of opinions, perhaps unsurprisingly:

What are the canonical moments of “Damn, I wish I had types here?” in a dynamic language?— mrb (@mrb_bk) April 29, 2014

The answers ranged from “never” to “always” to more thoughtful responses such as “during refactoring” or “when dealing with data from the outside world.” The latter sounded like a use case to me, so I started daydreaming about what a type checked model in a Rails application would look like, especially one that was primarily accessed through a controller that serves a JSON API.

Let’s look at a Post class:

class Post include PersistenceLogic attr_accessor :id attr_accessor :title attr_accessor :timestamp end

This post class includes some PersistanceLogic so that you can write:

Post.create({id: "foo", title: "bar", timestamp: 1398822693})

And be happy with yourself, secure that your data is persisted. To wire this up to the outside world, now imagine that this class is hooked up via a PostsController:

class PostsController def create Post.create(params[:post]) end end

Let’s assume that we don’t need to be concerned about security here (though that’s something that a richer type system can potentially help us with as well). This PostsController accepts some JSON:

{ "post": { "id": "0f0abd00", "title": "Cool Story", "timestamp": "1398822693" } }

And instead of having to write a bunch of boilerplate code around how to handle timestamp coming in as a string, or title not being present, etc. you could just write:

class Post rtc_annotated include PersistenceLogic typesig('@id: String') attr_accessor :id typesig('@title: String') attr_accessor :title typesig('@timestamp: Fixnum') attr_accessor :timestamp end

Which might lead you to want a type-checked build method (rtc_annotatetriggers type checking on a specific object instance):

class Post rtc_annotated include PersistenceLogic typesig('@id: String') attr_accessor :id typesig('@title: String') attr_accessor :title typesig('@timestamp: Fixnum') attr_accessor :timestamp typesig("self.build: (Hash) -> Post") def self.build(attrs) post = new.rtc_annotate("Post") post.id = attrs.delete(:id) post.title = attrs.delete(:title) post.timestamp = attrs.delete(:timestamp) end end

But, oops! When you run it you see that you didn’t write that correctly:

[2] pry(main)> Post.build({id: "0f0abd00", title: "Cool Story", timestamp: 1398822693}) Rtc::TypeMismatchException: invalid return type in build, expected Post, got Fixnum

You can fix that:

class Post rtc_annotated include PersistenceLogic typesig('@id: String') attr_accessor :id typesig('@title: String') attr_accessor :title typesig('@timestamp: Fixnum') attr_accessor :timestamp typesig("self.build: (Hash) -> Post") def self.build(attrs) post = new.rtc_annotate("Post") post.id = attrs.delete(:id) post.title = attrs.delete(:title) post.timestamp = attrs.delete(:timestamp) post end end

Okay let’s run it with that test JSON:

Post.build({ id: "0f0abd00", title: "Cool Story", timestamp: "1398822693" })

Whoah, whoops!

Rtc::TypeMismatchException: In method timestamp=, annotated types are [Rtc::Types::ProceduralType(10): [ (Fixnum) -> Fixnum ]], but actual arguments are ["1398822693"], with argument types [NominalType(1)<String>] for class Post

Ah, there ya go:

class Post rtc_annotated include PersistenceLogic typesig('@id: String') attr_accessor :id typesig('@title: String') attr_accessor :title typesig('@timestamp: Fixnum') attr_accessor :timestamp typesig("self.build: (Hash) -> Post") def self.build(attrs) post = new.rtc_annotate("Post") post.id = attrs.delete(:id) post.title = attrs.delete(:title) post.timestamp = attrs.delete(:timestamp).to_i post end end

So then you could say:

Post.build({ id: "0f0abd00", title: "Cool Story", timestamp: "1398822693" }).save

And be type-checked, guaranteed, and on your way.

Just a Taste

The idea behind this blog post was to get Ruby developers thinking about some of the advantages of using a sophisticated type checker that could programmatically enforce the kinds of specifications that are currently leveraged by documentation and tests. Through all of the debate about how much we should be testing and what we should be testing, we have been potentially overlooking another very sophisticated set of tools which can help augment our designs and guarantee the soundness of our programs over time.

The Ruby Type Checker alone will not give us all of the tools that we need, but it gives us a taste of what is possible with more focused attention on types from the implementors and users of the language.

Works Cited

[1] Gradual typing bibliography

[2] The ruby type checker [pdf]

Editor’s Note: Our post today is from Peter Bell. Peter Bell is Founder and CTO of Speak Geek, a contract member of the GitHub training team, and trains and consults regularly on everything from JavaScript and Ruby development to devOps and NoSQL data stores.

When you start a new project, automated tests are a wonderful thing. You can run your comprehensive test suite in a couple of minutes and have real confidence when refactoring, knowing that your code has really good test coverage.

However, as you add more tests over time, the test suite invariably slows. And as it slows, it actually becomes less valuable — not more. Sure, it’s great to have good test coverage, but if your tests take more than about 5 minutes to run, your developers either won’t run them often, or will waste lots of time waiting for them to complete. By the time tests hit fifteen minutes, most devs will probably just rely on a CI server to let them know if they’ve broken the build. If your test suite exceeds half an hour, you’re probably going to have to break out your tests into levels and run them sequentially based on risk – making it more complex to manage and maintain, and substantially increasing the time between creating and noticing bugs, hampering flow for your developers and increasing debugging costs.

The question then is how to speed up your test suite. There are a several ways to approach the problem. A good starting point is to give your test suite a spring clean. Reduce the number of tests by rewriting those specific to particular stories as “user journeys.” A complex, multi-page registration feature might be broken down into a bunch of smaller user stories while being developed, but once it’s done you should be able to remove lots of the story-specific acceptance tests, replacing them with a handful of high level smoke tests for the entire registration flow, adding in some faster unit tests where required to keep the comprehensiveness of the test suite.

In general it’s also worth looking at your acceptance tests and seeing how many of them could be tested at a lower level without having to spin up the entire app, including the user interface and the database.

Consider breaking out your model logic and treating your active record models as lightweight Data Access Objects. One of my original concerns when moving to Rails was the coupling of data access and model logic and it’s nice to see a trend towards separating logic from database access. A great side effect is a huge improvement in the speed of your “unit” tests as, instead of being integration tests which depend on the database, they really will just test the functionality in the methods you’re writing.

It’s also worth thinking more generally about exactly what is being spun up every time you run a particular test. Do you really need to connect to an internal API or could you just stub or mock it out? Do you really need to create a complex hairball of properly configured objects to test a method or could you make your methods more functional, passing more information in explicitly rather than depending so heavily on local state? Moving to a more functional style of coding can simplify and speed up your tests while also making it easier to reason about your code and to refactor it over time.

Finally, it’s also worth looking for quick wins that allow you to run the tests you have more quickly. Spin up a bigger instance on EC2 or buy a faster test box and make sure to parallelize your tests so they can leverage multiple cores on developers laptops and, if necessary, run across multiple machines for CI.

If you want to ensure your tests are run frequently, you’ve got to keep them easy and fast to run. Hopefully, by using some of the practices above, you’ll be able to keep your tests fast enough that there’s no reason for your dev team not to run them regularly.

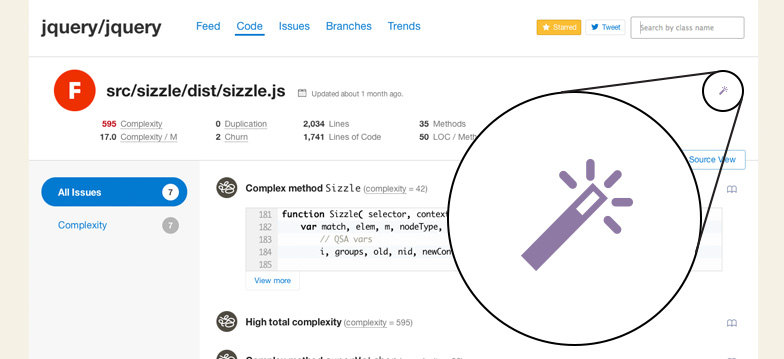

Code Climate is proud to announce a revolution in how software is built. To date, we’ve been providing developers actionable insights to help write maintainable code. The feedback, while useful, still requires care and collaboration to incorporate.

Today, we’re significantly streamlining the development process with our new Automated, 1-Click Refactoring feature.

Compared to the legacy approach of refactoring by hand, Automated Refactoring provides many advantages:

- Saves lots of time by replacing nuanced discussion with a definitive solution

- Appeases your CTO who has imposed an arbitrary, ill-defined requirement that all features must be “refactored” before they are shipped

- Works when you’re too lazy to go talk to that guy who worked on that thing one time

- Boosts your Git commit stats to get a bigger bonus at the end of the year

- As a substitute for head desk-inducing conversations with difficult team members

Here’s what David Heinemeier Hansson (DHH) had to say after testing it out:

“When most programmers refactor, they produce shit. Code Climate’s automated refactoring tool produces code that is decidedly not shit.”

Automated Refactoring is in public beta for all Code Climate customers, and select Open Source repos. To see it in action, navigate to a class you’ve been struggling to refactor and click the magic wand:

Automated Refactoring is free during our public beta period. Pricing is yet to be determined, but will be significant.

Editor’s Note: Automated Refactoring is no longer available. After April 1st, we determined that the feature was too revolutionary, and it was taken down. For posterity, the revolution was captured on YouTube.

Editor’s Note: Today we have a guest post from Marko Anastasov. Marko is a developer and cofounder of Semaphore, a continuous integration and deployment service, and one of Code Climate’s CI partners.

"The act of writing a unit test is more an act of design than of verification." - Bob Martin

A still common misconception is that test-driven development (TDD) is about testing; that by adhering to TDD you can minimize the probability of going astray and forgetting to write tests by mandating that is the first thing we need to do. While I’d pick a solution that’s designed for mere mortals over one that assumes we are superhuman any day, the case here is a bit different. TDD is designed to make us think about our code before writing it, using automated tests as a vehicle — which is, by the way, so much better than firing up the debugger to make sure that every code connected to a certain feature is working as expected. The goal of TDD is better software design. Tests are a byproduct.

Through the act of writing a test first, we ponder on the interface of the object under test, as well as of other objects that we need but that do not yet exist. We work in small, controllable increments. We do not stop the first time the test passes. We then go back to the implementation and refactor the code to keep it clean, confident that we can change it any way we like because we have a test suite to tell us if the code is still correct.

Anyone who’s been doing this has found their code design skills challenged and sharpened. Questions like agh maybe that private code shouldn’t be private or is this class now doing too much are constantly flying through your mind.

Test-driven refactoring

The red-green-refactor cycle may come to a halt when you find yourself in a situation where you don’t know how to write a test for some piece of code, or you do, but it feels like a lot of hard work. Pain in testing often reveals a problem in code design, or simply that you’ve come across a piece of code that was not written with the TDD approach. Some smells in test code are frequent enough to be called an anti-pattern and can identify an opportunity to refactor, both test and application code.

Take, for example, a complex test setup in a Rails controller spec.

describe VenuesController do let(:leaderboard) { mock_model(Leaderboard) } let(:leaderboard_decorator) { double(LeaderboardDecorator) } let(:venue) { mock_model(Venue) } describe "GET show" do before do Venue.stub_chain(:enabled, :find) { venue } venue.stub(:last_leaderboard) { leaderboard } LeaderboardDecorator.stub(:new) { leaderboard_decorator } end it "finds venue by id and assigns it to @venue" do get :show, :id => 1 assigns[:venue].should eql(venue) end it "initializes @leaderboard" do get :show, :id => 1 assigns[:leaderboard].should == leaderboard_decorator end context "user is logged in as patron" do include_context "patron is logged in" context "patron is not in top 10" do before do leaderboard_decorator.stub(:include?).and_return(false) end it "gets patron stats from leaderboard" do patron_stats = double leaderboard_decorator.should_receive(:patron_stats).and_return(patron_stats) get :show, :id => 1 assigns[:patron_stats].should eql(patron_stats) end end end # one more case omitted for brevity end end

The controller action is technically not very long:

class VenuesController < ApplicationController def show begin @venue = Venue.enabled.find(params[:id]) @leaderboard = LeaderboardDecorator.new(@venue.last_leaderboard) if logged_in? and is_patron? and @leaderboard.present? and not @leaderboard.include?(@current_user) @patron_stats = @leaderboard.patron_stats(@current_user) end end end end

Notice how the extensive spec setup code basically led the developers to forget to write expectations that Venue.enabled.find is called, or LeaderboardDecorator.new is given a correct argument, for example. It is not clear if the assigned @leaderboard comes from the assigned venue at all.

Trapped in the MVC paradigm, the developers (myself included) were adding up some deep business logic in the controller, making it hard to write a good spec and thus maintain both of them. The difficulty comes from the fact that even a one-line Rails controller method does many things:

def show @venue = Venue.find(params[:id]) end

That method is:

- extracting parameters;

- calling an application-specific method;

- assigning a variable to be used in the view template; and

- rendering a response template.

Adding code that reaches deep inside the database and business rules can only turn a controller method into a mess.

The controller above includes one if statement with four conditions. A full spec, then, should include 15 combinations just for this one part of code. Of course they were not written. But things could be different, if this code was outside the controller.

Let’s try to imagine what a better version of the controller spec would look like, and what interfaces it would prefer to work with in order to carry its’ job of processing the incoming request and preparing a response.

describe VenuesController do let(:venue) { mock_model(Venue) } describe "GET show" do before do Venue.stub(:find_enabled) { venue } venue.stub(:last_leaderboard) end it "finds the enabled venue by given id" do Venue.should_receive(:find_enabled).with(1) get :show, :id => 1 end it "assigns the found @venue" do get :show, :id => 1 assigns[:venue].should eql(venue) end it "decorates the venue's leaderboard" do leaderboard = double venue.stub(:last_leaderboard) { leaderboard } LeaderboardDecorator.should_receive(:new).with(leaderboard) get :show, :id => 1 end it "assigns the @leaderboard" do decorated_leaderboard = double LeaderboardDecorator.stub(:new) { decorated_leaderboard } get :show, :id => 1 assigns[:leaderboard].should eql(decorated_leaderboard) end end end

Where did all the other code go? We’re simplifying the find logic by extending the model:

describe Venue do describe ".find_enabled" do before do @enabled_venue = create(:venue, :enabled => true) create(:venue, :enabled => true) create(:venue, :enabled => false) end it "finds within the enabled scope" do Venue.find_enabled(@enabled_venue.id).should eql(@enabled_venue) end end end

The various if statements can be simplified as follows:

if logged_in?– variations on this can be decided in the view template;if @leaderboard.present?– obsolete, the view can decide what to do if it is not;- The rest can be moved to the decorator class under a new, more descriptive method.

describe LeaderboardDecorator do describe "#includes_patron?" do context "user is not a patron" { } context "user is a patron" do context "user is on the list" { } context "user is NOT on the list" { } end end end

This new method will help the view decide whether or not to render @leaderboard.patron_stats, which we do not need to change:

# app/views/venues/show.html.erb <%= render "venues/show/leaderboard" if @leaderboard.present? %> # app/views/venues/show/_leaderboard.html.erb <% if @leaderboard.includes_patron?(@current_user) -%> <%= render "venues/show/patron_stats" %> <% end -%>

The resulting controller method is now fairly simple:

def show @venue = Venue.find_enabled(params[:id]) @leaderboard = LeaderboardDecorator.new(@venue.last_leaderboard) end

The next time we work with this code, we might be annoyed that controller needs to know what is the right argument to give to a LeaderboardDecorator. We could introduce a new decorator for venues that will have a method that returns a decorated leaderboard. The implementation of that step is left as an exercise for the reader.

Editor’s Note: Today we have a guest post from Oren Dobzinski. Oren is a code quality evangelist, actively involved in writing and educating developers about maintainable code. He blogs about how to improve code quality at re-factor.com.

It’s the beginning of the project. You already have a rough idea of the architecture you’re going to build and you know the requirements. If you’re like me you’ll want to just start coding, but you hold yourself back, knowing that you should really start with an acceptance test.

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. Your system needs to talk to a datastore or two, communicate with a couple internal services, and maybe an external service as well. Since it’s hard to build both the infrastructure and the business logic at the same time you make a few assumptions in your test and stub out these dependencies, adding them to your TODO list.

A couple of weeks pass, the deadline is getting close, and you come back to your list. But while working on the integration you find out that it’s really a pain to setup one of the datastores, and that there are a few security-related issues with the external service you need to sort out with the in-house security team. You also discover that the behavior of the external service is not what you expected. Maybe the service is slower than you anticipated, or requires multiple requests that weren’t well-documented or just because you don’t have a premium account. Oh, and you left the deployment scripts for the end so now you need to start cranking on that.

Naturally, it’s more complicated than you originally thought. At this point you’re deep in crunch mode and realize you might not hit the deadline because of the additional work you’ve just discovered and the need to wait for other teams for their input.

Deploy A Walking Skeleton First

In order to reduce risks on projects like the above you need to figure out all the unknowns as early as possible. The best way to do this is to have a real end-to-end test with no stubs against a system that’s deployed in production. Enter the Walking Skeleton: a “tiny implementation of the system that performs a small end-to-end function. It need not use the final architecture, but it should link together the main architectural components. The architecture and the functionality can then evolve in parallel.” – Alistair Cockburn. It is discussed extensively in the excellent GOOS book.[1]

If the system needs to talk to one or more datastores then the walking skeleton should perform a simple query against each of them, as well as simple requests against any external or internal service. If it needs to output something to the screen, insert an item to a queue or create a file, you need to exercise these in the simplest possible way. As part of building it you should write your deployment and build scripts, setup the project, including its tests, and make sure all the automations are in place — such as CI integration, monitoring and exception handling. The focus is the infrastructure, not the features. Only after you have your walking skeleton should you write your first acceptance test and begin the TDD cycle.

This is only the skeleton of the application, but the parts are connected and the skeleton does walk in the sense that it exercises all the system’s parts as you currently understand them. Because of this partial understanding, you must make the walking skeleton minimal. But it’s not a prototype and not a proof of concept — it’s production code, so you should definitely write tests as you work on it. These tests will assert things like “accepts a request”, “pushes some content to S3”, or “pushes an empty message to the queue”.

[1] A similar concept called “Tracer Bullets” was introduced in The Pragmatic Programmer.

Start with the Riskiest Task

According to Hofstadter’s Law, “it always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.” Amazingly, the law is always spot on. It makes sense then to work on the riskiest parts of the project first, which are usually the parts which have dependencies: on third party services, on in house services, on other groups in the organization you belong to. It makes sense to get the ball rolling with these groups simply because you don’t know how long it will take and what problems should arise.

Don’t Cut Corners

It’s important to stress that until the walking skeleton is deployed to production (possibly behind a feature flag or just hidden from the outside world) you are not ready to write the first acceptance test. You want to exercise your deployment and build scripts and discover as many potential problems as you can as early as possible.

The Walking Skeleton is a way to validate the design and get early feedback so that it can be improved. You will be missing this feedback if you cut corners or take shortcuts.

Kickstart the TDD process

You can also think about it as a way to start the TDD process. It can be daunting or just too much work to build the infrastructure along with the first acceptance test. Furthermore, changes in one may require changes in the other (it’s the “first-feature paradox” from GOOS). This is why you first work on the infrastructure and only then move on to work on the first feature.

Obstacles and Tradeoffs

By front-loading all infrastructure work you’re postponing the delivery of the first feature. Some managers might feel uncomfortable when this happens, as they expect very rapid pace at the beginning of the project. You might feel some pressure to cut corners. However, their confidence should increase when you deliver the walking skeleton and they have a real, albeit minimal, system to play with. Most hard problems in software development are communication problems, and this is no exception. You should explain how the walking skeleton will reduce unexpected delays at the end of the project.

The walking skeleton may not save you from the recursiveness of Hofstadter’s Law but it may make the last few days of the project a little more sane.

Editor’s Note: Today we have a guest post from Brandon Savage, an expert in crafting maintainable PHP applications. We invited Brandon to post on the blog to share some of his wisdom around bringing object-oriented design to PHP, a language with procedural roots.

One of the most common questions that PHP developers have about object-oriented programming is, “why should I bother?” Unlike languages such as Python and Ruby, where every string and array is an object, PHP is very similar to its C roots, and procedural programming is possible, if not encouraged.

Even though an object model exists in PHP, it’s not a requirement that developers use it. In fact, it’s possible to build great applications (see WordPress) without object-orientation at all.

So why bother?

There are five good reasons why object-oriented PHP applications make sense, and why you should care about writing your applications in an object-oriented style.

1. Objects are extensible.

It should be possible to extend the behavior of objects through both composition and inheritance, allowing objects to take on new life and usefulness in new settings.

Of course, developers have to be careful when extending existing objects, since changing the public API of an object creates a whole new object type. But, if done well, developers can revitalize old libraries through the power of inheritance.

2. Objects are replaceable.

The whole point of object-oriented development is to make it easy to swap objects out for one another. The Liskov Substitution Principle tells us that one object should be replaceable with another object of the same type and that the program should still work.

It can be hard to see the value in removing a component and replacing it with another component, especially early on in the development lifecycle. But the truth is that things change; needs, technologies, resources. There may come a point where you’ll need to incorporate a new technology, and having a well-designed object-oriented application will only make that easier.

3. Objects are testable.

It’s possible to test procedural applications, albeit not well. Most procedural applications don’t have an easy way to separate external components (like the file system, database, etc.) from the components under test. This means that under the best circumstances, testing a procedural application is more of an integration test than a unit test.

Object-oriented development makes unit testing far easier and more practical. Since you can easily mock and stub objects (see Mockery, a great mock object library), you can replace the objects you don’t need and test the ones you do. Since a unit test should be testing only one segment of code at a time, mock and stub objects make this possible.

4. Objects are maintainable.

There are a few problems with procedural code that make it more difficult to maintain. One is the likelihood of code duplication, that insidious parasite of unmaintainability. Object-oriented code, on the other hand, makes it easy for developers to put code in one place, and to create an expressive API that explains what the code is doing, even without having to know the underlying behavior.

Another problem that object-oriented programming solves is the fact that procedural code is often complicated. Multiple conditional statements and varying paths create code that is hard to follow. There’s a measure of complexity — cyclomatic complexity — that shows us the number of decision points in the code. A score greater than 12 is usually considered bad, but good object-oriented code will generally have a score under 6.

For example, if you know that a method accepts an object as one of its arguments, you don’t have to know anything about how that object works to meet the requirements. You don’t have to format that object, or manipulate the data to meet the needs of the method; instead, you can just pass the object along. You can further manipulate that object with confidence, knowing that the object will properly validate your inputs as valid or invalid, without you having to worry about it.

5. Objects produce catchable (and recoverable) errors.

Most procedural PHP developers are passingly familiar with throwing and catching exceptions. However, exceptions are intended to be used in object-oriented development, and they are best used as ways to recover from various error states.

Exceptions are catchable, meaning that they can be handled by our code. Unlike other mechanisms in PHP (like trigger_error()), we can decide how to handle an exception and determine if we can move forward (or terminate the application).

The Bottom Line

Object-oriented programming opens up a whole world of new possibilities for developers. From testing to extensibility, writing object-oriented PHP is superior to procedural development in almost every respect.

Exercising Your Team’s Refactoring Muscles Together

When teams try to take control of their technical debt and improve the maintainability of their codebase over time, one problem that can crop up is a lack of refactoring experience. Teams are often composed of developers with a mix of experience levels (both overall and within the application domain) and stylistic preferences, making it difficult for well-intentioned contributors to effect positive change.

There are a variety of techniques to help in these cases, but one I’ve had success with is “Mob Refactoring”. It’s a variant of Mob Programming, which is like pair programming with more than two people (though still with one computer). This sounds crazy at first, and I certainly don’t recommend working like this all the time, but it can be very effective for leveling up the refactoring abilities of the team and establishing shared conventions for style and structure of code.

Here’s how it works:

- Assemble the team for an hour around a computer and a projector. It’s a great opportunity to order food and eat lunch together, of course.

- Bring an area of the codebase that is in need of refactoring. Have one person drive the computer, while the rest of the team navigates.

- Attempt to refactor the code as much as possible within the hour.

- Don’t expect to produce production-ready code during these sessions. When you’re done, throw out the changes. Do not try to finish the refactoring after the session – it’s an easy way to get lost in the weeds.

The idea is that the value of the exercise is in the conversations that will take place, not the resulting commits. Mob Refactoring sessions provide the opportunity for less experienced members of the team to ask questions like, “Why do we do this like that?”, or for more senior programmers to describe different implementation approaches that have been tried, and how they’ve worked out in the past. The discussions will help close the experience gap and often lead to a new consensus about the preferred way of doing things.

Do this a few times, and rotate the area of focus and the lead each week. Start with a controller, then work on a model, or perhaps a troublesome view. Give each member of the team a chance to select the code to be refactored and drive the session. Even the least experienced member of your team can pick a good project – and they’ll probably learn more while by working on a problem that is on the top of their mind.

If you have a team that wants to get better at refactoring, but experience and differing style patterns are a challenge, give Mob Refactoring a try. It requires little preparation, and only an hour of investment (although I would recommend trying it three times before judging the effect). If you give it a go, let me know how it went for you in the comments.