Sasha Rezvina

Balanced test suites for long-term maintainability

Are your tests running slower than you’d like? Or perhaps your tests are brittle, making it harder to refactor and make substantial changes to your application functionality? Both are common complaints for large Rails apps that have been around for years, but good testing practices shouldn’t create these problems over the long term.

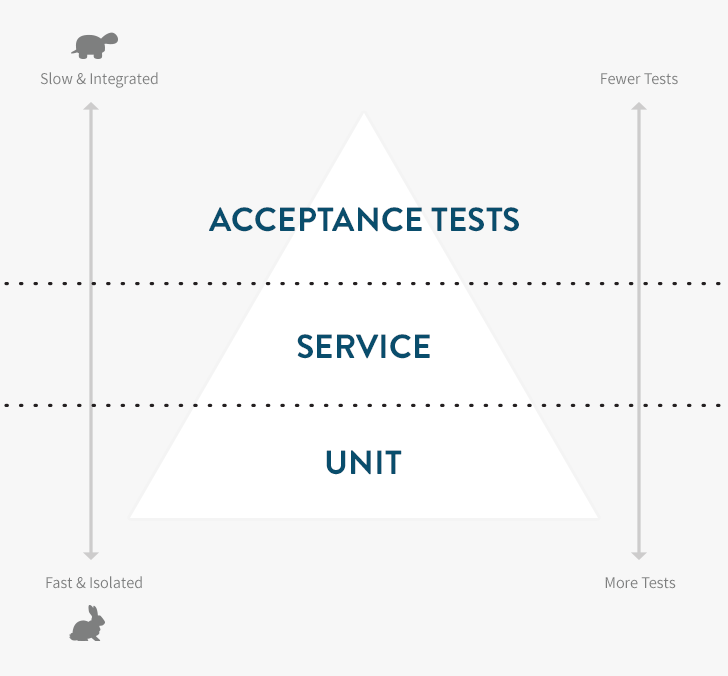

The testing pyramid is a concept that can help you better balance your tests, speeding up your test suite and reducing the cost of changing the functionality of your applications. It centers on the composition of different types of tests in your suite.

You’re probably already familiar with the two most common types of Rails tests in the wild:

- ** Unit tests** — The lowest and most important level. Unit tests use tools like RSpec, MiniTest or Jasmine that confirm the correct behavior of isolated units of functionality (typically classes, methods or functions), and run extremely fast (milliseconds).

- Acceptance tests — The high level (typically user-level) tests using tools like RSpec and Capybara, Cucumber or Selenium. Since they run a lot more code than unit tests and often depend on external services they are much slower (seconds or minutes).

A properly tested application feature requires both unit tests and acceptance tests. Start by making sure you have good unit test coverage. This is a natural by-product of a test-driven development (TDD) workflow. Your unit tests should catch edge cases and confirm correct object behavior.

Carefully supplement your unit tests with acceptance tests that exercise the application like an end-user. These will give you confidence that all of the objects are playing nicely together. Teams often end up with way too many of these tests, slowing development cycles to a crawl. If you have 20 Capybara-based tests for user registration to confirm that all validation errors are handled correctly, you’re testing at the wrong level. This is known as the Inverted Testing Pyramid anti-pattern.

The Throwaway Test

It’s important to realize that — just like scaffolding — a test can be useful without being permanent. Imagine that you’re going to spend two weeks building a complex registration system, but you’re slicing it into half day stories each of which has a couple of Cucumber tests to verify behavior. This can be a good way to develop, as you’ve got a large number of thinly-sliced stories and are ensuring that you have clear “confirmation” that each story is complete in the form of passing acceptance tests. Just don’t forget the final step: When you’re done, pare your test suite down to the minimum set of tests to provide the confidence you need (which may vary depending on the feature).

Once you’re done with such a minimum marketable feature, instead of just shipping with the 40-50 acceptance tests you used while building out the stories, you should replace those with maybe 3-5 user journeys covering the major flows through the registration system. It’s OK to throw away the other tests, but make sure that you’re still ensuring correctness of the key behaviors — often by adding more unit tests. If you don’t do this, you’ll quickly end up with a test suite that requires substantial parallelization just to run in 5-8 minutes and that is brittle with small UI changes breaking large numbers of tests.

Service-Level Testing

Eventually, you’ll notice that there is sometimes functionality that you can’t confidently test at a unit level but that shouldn’t really be tested via the UI. In his 2009 book, “Succeeding with Agile”, Mike Cohn (who came up with the concept of “the testing pyramid” which was later popularized by Martin Fowler) used the phrase “service-level testing” to describe these tests. Various communities also use terms like functional or integration tests which also describe tests between unit and end-to-end acceptance tests.

The trick with service level testing is to expose an API for your application or subsystem so that you can test the API independently of the UI that will exercise it. This ties in nicely with trends in web application development where many teams are now trending towards building a single RESTful JSON API on the server side to service both web and native mobile clients.

Putting It All together

Most applications only have a small number of critical user paths. For an eCommerce application, they might be:

- Browsing the product catalog

- Buying a product

- Creating an account

- Logging in (including password reset)

- Checking order history

As long as those five things are working, the developers don’t need to be woken up in the middle of the night to fix the application code. (Ops is another story.) Those functions can likely be covered with five coarse-grained, Capybara tests that run in under two minutes total.

Blending unit tests, service-level tests and acceptance tests yields faster test suites that still provide confidence the application is working, and are resistant to incidental breakage. As you develop, take care to prune tests that are not pulling their weight. When you fix a bug, implement your regression test at the lowest possible level. Over time, keep an eye on the ratio between the counts of each type of test, as well as the time of your acceptance test suite.

Using these techniques, you can achieve testing nirvana: A suite that provides you confidence the application works, gives you freedom to change the application without brittle, UI-related test failures, and runs in a few minutes without any parallelization.

Peter Bell is Founder and CTO of Speak Geek, a contract member of the GitHub training team, and trains and consults regularly on everything from JavaScript and Ruby development to devOps and NoSQL data stores.

Code quality and test coverage information often live in separate silos. Code Climate has always been able to help you understand the complexity of your code, but to look at your test coverage required a different set of tools (like SimpleCov). This made it harder than necessary to answer key questions like:

- “Which areas of my app are both low quality and untested?”

- “How well covered is this method I’m about to refactor?”

- “Should I beef up integration testing coverage before this large-scale change?”

Today, we’re proud to announce the full integration of test coverage metrics into Code Climate. To make it dead simple to get started, we’re also partnering with three awesome companies that are experts at running your tests – Semaphore, Solano Labs, and Travis CI. (More on this below.)

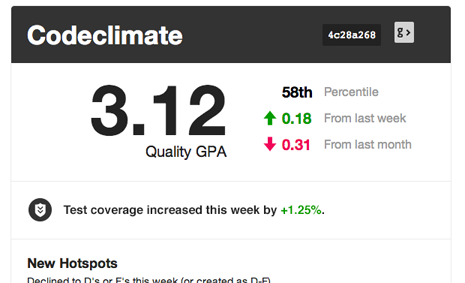

Having test coverage side-by-side with code quality enables your team to make better decisions earlier in your development process, leading to more maintainable code that is easier to work in. Here’s a quick look:

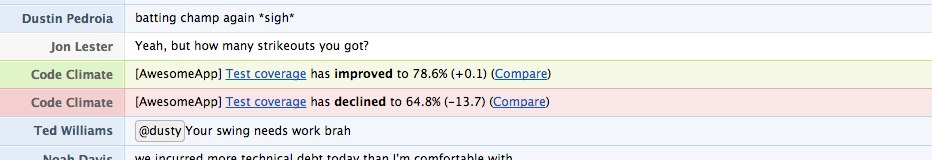

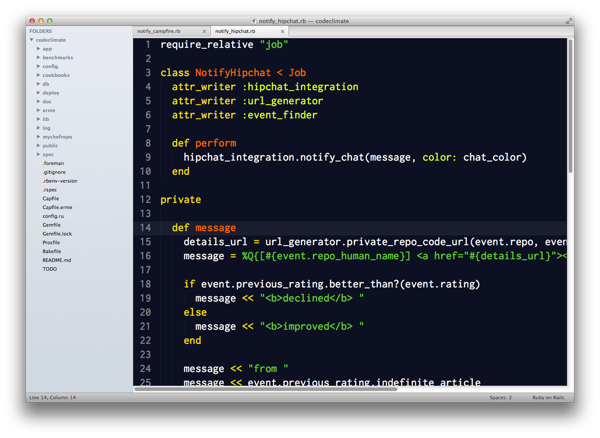

Just like with code quality, we surface test coverage information at the repository, class, and source listing level (down to an individual line of code) and provide feedback as metrics change over time in the form of email alerts, activity feeds, chat notifications and RSS.

With just a few minutes of setup you can:

- View test coverage reports for each class alongside other metrics like complexity, duplication, and churn.

- Toggle between viewing code smells and test coverage line-by-line on the same source listings (see above).

- Track your team’s test coverage in your weekly summary emails and Code Climate feed.

Here’s a couple examples of Code Climate’s test coverage integration …

… in your chatroom:

… and in your weekly summary email:

We think the addition of test coverage to our code quality offering is a powerful upgrade in our mission of helping free teams from the burden of technical debt and unmaintainable code. Give it a try today, and let us know what you think.

How does test coverage work?

Code Climate does not run your code, and that’s not changing. Instead, our new test coverage feature works by accepting coverage data sent from wherever you are already running your tests. This means you can use Code Climate’s new test coverage feature with your existing continuous integration (CI) server. (In a pinch, you could even send up test coverage data from your laptop, or anywhere else.)

We’ve released the codeclimate-test-reporter RubyGem that you install into your Gemfile. When your tests finish, it sends an HTTPS post to us with a report on which lines of code were executed (and how many times).

Test Coverage is included in all our currently offered plans. To turn it on for a specific repo, just go to your repository’s feed page, click “Set up Test Coverage” and follow the instructions.

Our Partners

Some of you might not have a CI server in place for your project, or perhaps you’ve been frustrated maintaining your own CI server and are looking for something better. We believe cloud-based CI is the future and are excited to partner with three fantastic CI providers – Semaphore, Solano Labs, and Travis CI – to ensure you can integrate their services with just a few clicks.

All three of our partners save you from the headaches of administering a CI server (like Jenkins) on your own – time and money that adds up quickly. If you’re looking to make a move to a cloud CI vendor, now is a great time.

Joining forces with three companies that are experts at running your tests – safely, quickly and with little effort – means we can stay focused on what we do best. To get started with one of these great partner offers, login to your Code Climate account and head to the Test Coverage setup tab for one of your repos.

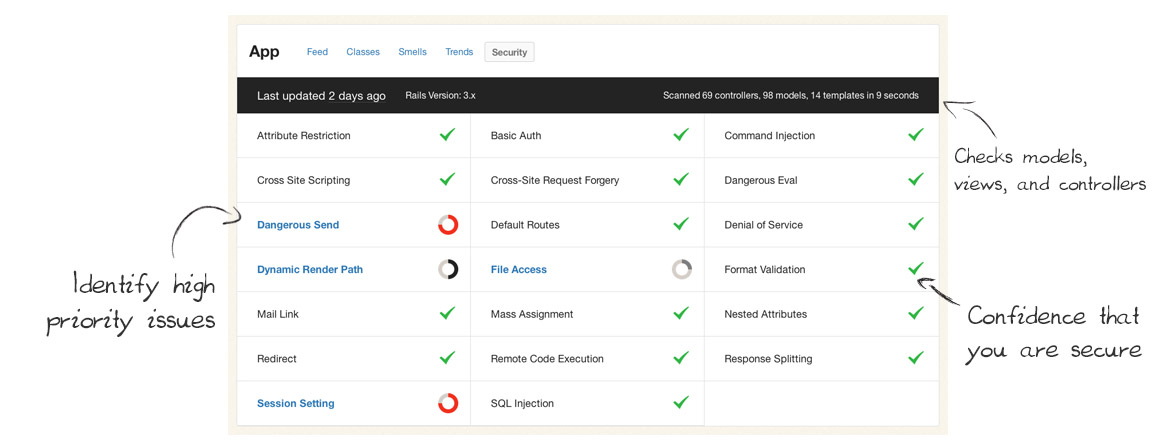

Today we’re very excited to publicly launch our new Security Monitor feature! It’s our next step in bringing you clear, timely and actionable information from your codebase.

Security Monitor regularly scans your Rails apps and lets your team know as soon as new potential vulnerabilities are found. It keeps your app and data safe by catching common security issues code before they reach production.

Some large organizations employ security specialists to review every commit before they go live, but many teams can’t afford that cost and the slowdown on their release cycles. Security Monitor gives you a second set of eyes on every commit – eyes that are well trained to spot common Rails security issues – but much faster and at a fraction of the cost.

(We love security experts, we just think their time is better spent on the hard security problems rather than common, easily detectible issues.)

Code Climate keeps getting better

We’ve been astonished and humbled by the growth of Code Climate over the past year. What began as a simple project to make static analysis easy for Ruby projects has grown into much more than that. The praise has been overwhelming:

“I’ve only been using Code Climate for about 10 minutes and it’s already become one of the most useful tools we have access to.” —Ryan Kee

Every day we work to make the product even better for our customers. Since we’ve launched, we’ve added things like:

- Easy-to-understand A-F ratings for each class and Quality GPAs

- Class Compare view for identifying exactly what changed

- Quality alerts and totally new weekly summary emails

- Trends charts and churn metrics

- GitHub, Pivotal Tracker, and Lighthouse integration

Now that Security Monitor is out the door, the next big feature we are working on is Branch Testing. Soon, you’ll be able to easily see the quality changes and new security risks of every feature branch and pull request before they get merged into master.

Changes to our pricing

Our current plans have been in place for over a year, and the product has changed tremendously in that time. We believe (and we’ve been told many times) that Code Climate is much more valuable today than it was when started.

Additionally, Security Monitor has proven to be incredibly valuable to teams looking for help trying to catch risky code before it makes its way into production. We wouldn’t be able to offer it on all plans, so we’re making some changes.

Today we’re rolling out new plans for private accounts:

I’d like to address some common questions…

I’m a current customer. How does this affect me?

We love you. Your support was key to getting Code Climate to this point. The plan you’re currently on isn’t changing at all, and won’t for at least two years.

Also, we think if you’re running Rails in a commercial capacity you’d strongly benefit from upgrading to our Team plan, which has the Security Monitor feature we talked about above.

To make that a no-brainer decision for you, we’ll comp you $25 a month for the next two years if you upgrade to a Team, Company or Enterprise plan before April 2nd. Look for an email with a link to upgrade arriving today (Tuesday, March 19th).

Also, big new features like Branch/Pull Request Testing will only be available on the new plans, upgrade now to avoid missing out on this big, one-time discount.

I’m on the fence about Code Climate. What should I do?

To make it easy for you to get off the fence, we’re extending a discount of $25/month for the next two years ($600 value) if you start a free trial before April 2nd. Now is the best time to start a free trial and lock in that discount.

Why charge per user?

Ultimately, it is best for you guys, our customers, if our pricing creates a vibrant, sustainable company that can be here for the long haul and improving Code Climate so that it continues to create massive value for your businesses.

Within that overarching goal, we’d like our pricing to scale with customer success: we’d like entry-level users to be able to get started without sacrificing too much ramen and for extraordinarily successful software companies to pay appropriately given the value Code Climate creates for them.

It turns out that per-repository pricing doesn’t necessarily proxy customer success all that well: Google, for example, is rumored to have a grand total of one Perforce repository. Many smaller teams (like the good folks at Travis CI) have dozens, given that Git encourages a one-repo-per-project workflow. To more appropriately balance prices between small teams and the Google’s of the world (not technically a customer yet but hey, Larry, call me), we’re adding a per-user component to pricing.

This largely affects larger commercial enterprises which are used to per-seat licensing, have defined budgets for per-employee expenses (like healthcare, training, and equipment, next to which Code Climate is very reasonably priced), and can easily see the substantial business value created by lowering software maintenance costs, keeping projects on track, and reducing security risk.

It also lets us invest substantially in development operations to support new features like Security Monitor which are most critically needed by larger teams, while keeping the basic Code Climate offering available and reasonably priced for all teams and 100% free for open source projects.

I’m a student or non-profit. Can you help?

Yes. We now offer educational and non-profit discounts to qualifying people and organizations. We’re interested in supporting you.

Code Climate hit an exciting milestone last week: in the seven months since we launched our free OSS service we’ve added 5,000 Ruby projects. Code Climate is built on open source software, so we’re especially thrilled for the service to be adopted by the community.

We’re also incredibly grateful to our hosting partners Blue Box whose support makes it possible to provide this service free for OSS! Blue Box has provided us great uptime, dependable monitoring and support, and help planning for our continued growth. I definitely encourage everyone to check them out. Thanks guys!

Code quality can be especially important for OSS because there are many contributors involved. We try to make it easy to monitor overall quality by providing projects with a “Quality GPA” calculated by aggregating the ratings for each class, weighted by lines of code, into an average from 0 to 4.0.

Fun fact: The average open source project on Code Climate has a GPA of 3.6 – which we thinks speaks volumes about the culture of quality in the Ruby open source community. Andy Lindeman, project lead for rspec-rails, explained:

Code Climate helps keep both the core team and contributors accountable since we display the GPA badge at the top of the READMEs. The GPA is useful in finding pieces of code that would benefit from a refactor or redesign, and the feed of changes (especially when things “have gotten worse”) is useful to nip small problems before they become big problems.

Erik Michaels-Ober also uses Code Climate for his many RubyGems and noted, “I spent one day refactoring the Twitter gem with Code Climate and it dramatically reduced the complexity and duplication in the codebase. If you maintain an open source project, there’s no excuse not to use it.”

Curious about your project’s GPA? Just provide the name of the repo on the Add GitHub Repository page. Code Climate will clone the project, analyze it, and shoot you an email when the metrics are ready – all in a couple of minutes. Once you’ve added your project, you can show off your code’s GPA by adding a dynamic badge (designed by Oliver Lacan and part of his open source shields project) to your project’s README or site.

Here’s to the next 5,000 projects!

Our latest post comes from Giles Bowkett. Giles recently wrote a book, Rails As She Is Spoke, which explores Rails’ take on OOP and its implications. It’s an informative and entertaining read, and you should buy it.

A few days ago I wrote a blog post arguing that rails developers should take DCI seriously. Be careful what you wish for! A tumultuous brouhaha soon ensued on Twitter. I can’t necessarily take the credit for that, but I’m glad it happened, because one of the people at the center of the cyclone, Rails creator David Heinemeier Hansson, wrote a good blog post on ActiveSupport::Concern, which included a moment of taking DCI seriously.

[…] breaking up domain logic into concerns is similar in some ways to the DCI notion of Roles. It doesn’t have the run-time mixin acrobatics nor does it have the “thy models shall be completely devoid of logic themselves” prescription, but other than that, it’ll often result in similar logic extracted using similar names.

DCI (data, context, and interaction) is a paradigm for structuring object-oriented code. Its inventor, Trygve Reenskaug, also created MVC, an object-oriented paradigm every Rails developer should be familiar with. Most Rubyi mplementations use mixins quite a lot, and there is indeed some similarity there.

However, there’s a lot more to DCI than just mixins, and since I’ve already gone into detail about it elsewhere, as have many others, I won’t get into that here. I’m very much looking forward to case studies from people who’ve used it seriously. Likewise, there are a lot of good reasons to feel cautious about using mixins, either for Rails concerns or for DCI, but that discussion’s ongoing and deserves (and is receiving) several blog posts of its own.

What I want to talk about is this argument in Hansson’s blog post:

I find that concerns are often just the right amount of abstraction and that they often result in a friendlier API. I far prefer current_account.posts.visible_to(current_user) to involving a third query object. And of course things like Taggable that needs to add associations to the target object are hard to do in any other way. It’s true that this will lead to a proliferation of methods on some objects, but that has never bothered me. I care about how I interact with my code base through the source.

I added the emphasis to the final sentence because I think it’s far more important than most people realize.

To explain, I want to draw an example from my new book Rails As She Is Spoke, which has a silly title but a serious theme, namely the ways in which Rails departs from traditional OOP, and what we can learn from that. The example concerns the familiar method url_for. But I should say “methods,” because the Rails code base (as of version 3.2) contains five different methods named url_for.

The implementations for most of these methods are hideous, and they make it impossible not to notice the absence of a Url class anywhere in the Rails code base — a truly bizarre bit of domain logic for a Web framework not to model — yet these same, hideously constructed methods enable application developers to use a very elegant API:

url_for controller: foo, action: bar, additional: whatnot

Consider again what Hansson said about readable code:

I care about how I interact with my code base through the source.

I may be reading too much into a single sentence here, but after years of Rails development, I strongly believe that Rails uses this statement about priorities as an overarching design principle. How else do you explain a Web framework that does not contain a Url class within its own internal domain logic, yet provides incredible conveniences like automated migrations and generators for nearly every type of file you might need to create?

The extraordinary internal implementation of ActiveRecord::Base, and its extremely numerous modules, bends over backwards to mask all the complexity inherent in instantiating database-mapping objects. It does much, much less work to make its own internal operations easy to understand, or easy to reason about, or easy to subclass, and if you want to cherry-pick functionality from ActiveRecord::Base, your options span a baffling range from effortless to impossible.

Consider a brief quote from this recent blog post on the params object in Rails controllers:

In Ruby, everything is an object and this unembarrassed object-orientation gives Ruby much of its power and expressiveness. […] In Rails, however, sadly, there are large swathes which are not object oriented, and in my opinion, these areas tend to be the most painful parts of Rails.

I agree with part of this statement. I think it’s fair to say that Ruby takes its object-oriented nature much more seriously than Rails does. I also agree that customizing Rails can be agonizingly painful, whenever you dip below the framework’s beautifully polished surface into the deeper realms of its code, which is sometimes object-oriented and sometimes not. But if you look at this API:

url_for controller: foo, action: bar, additional: whatnot

It doesn’t look like object-oriented code at all. An object-oriented version would look more like this:

Url.new(:foo, :bar, additional: whatnot)

The API Rails uses looks like Lisp, minus all the aggravating parentheses.

(url_for ((controller, 'foo), (action, 'bar), (additional, whatnot)))

That API is absolutely not, in my opinion, one of “the most painful parts of Rails.” It’s one of the least painful parts of Rails. I argue in my book that Rails owes a lot of its success to creating a wonderful user experience for developers — making it the open source equivalent of Apple — and I think this code is a good example.

Rails disregards object orientation whenever being object-oriented stands in the way of a clean API, and I actually think this is a very good design decision, with one enormous caveat: when Rails first debuted, Rails took a very firm position that it was an opinionated framework very highly optimized for one (and only one) particular class of Web application.

If (and only if) every Rails application hews to the same limited range of use cases, and never strays from the same narrow path of limited complexity, then (and onlythen) it makes perfect sense to prioritize the APIs which developers see over their ability to reason about the domain logic of their applications and of the framework itself.

Unfortunately, the conditions of my caveat do not pertain to the overwhelming majority of Rails apps. This is why Rails 3 abandoned the hard line on opinionated software for a more conciliatory approach, which is to say that Rails is very highly optimized for a particular class of Web application, but sufficiently modular to support other types of Web applications as well.

If you take this as a statement about the characteristics of Rails 3, it’s outrageously false, but if you take it as a design goal for Rails 3 and indeed (hopefully) Rails 4, it makes a lot of sense and is a damn good idea.

In this context, finding “just the right amount of abstraction” requires more than just defining the most readable possible API. It also requires balancing the most readable possible API with the most comprehensible possible domain model. There’s an analogy to human writing: you can’t just write beautiful sentences and call it a day. If you put beautiful sentences on pages at random, you might have poetry, if you get lucky, but you won’t have a story.

This is an area where DCI demolishes concerns, because DCI provides an entire vocabulary for systematic decomposition. If there’s any guiding principle for decomposing models with concerns, I certainly don’t recall seeing it, ever, even once, in my 7 years as a Rails developer. As far as I can tell the closest thing is: “Break the class into multiple files if…”

- There are too many lines of code.

- It’s Tuesday.

- It’s not Tuesday.

DCI gives developers something more fine-grained.

I’m not actually a DCI zealot; I’m waiting until I’ve built an app with DCI and had it running for a while before I make any strident or definitive statements. The Code Climate blog itself featured some alternative solutions to the overburdened models problem, and these solutions emphasize classes over mixins. You could do worse than to follow them to the letter. Other worthwhile alternatives exist as well; there is no silver bullet.

However, Rails concerns are just one way to decompose overburdened models. Concerns are appropriate for some apps and inappropriate for others, and I suspect the same is true of DCI. Either way, if you want to support multiple types of applications, with multiple levels and types of complexity, then making a blanket decision about “just the right amount of abstraction” is pretty risky, because that decision may in fact function at the wrong level of abstraction itself.

It doesn’t take a great deal of imagination to understand that different apps feature different levels of complexity, and you should choose which technique you use for managing complexity based on how much complexity you’re going to be managing. As William Gibson said, “the street finds its own uses for things,” and I think most Rails developers use Rails to build apps that are more complex than the apps Rails is optimized for. I’ve certainly seen apps where that was true, and in those apps, concerns did not solve the problem.

It’s possible this means people should be using Merb instead of Rails, although that train appears to have left the station (and of course it left the station on Rails).

Today I’m excited to announce that Code Climate is free for open source projects. Many open source projects were added during the closed beta, and you can see them all on the new Explore page. (To learn more about what Code Climate provides and how it works, check out the homepage.)

This has been in the plans since the beginning and was one of the common requests since the launch for private accounts. It feels great to finally have it out the door. My hope is that Code Climate becomes as valuable a tool to Ruby open source development as Travis CI.

Code quality is especially important for OSS because of the large number of contributors they attract. Now quality metrics can complement a suite of automated tests to help ensure you’re shipping rock solid releases. Look out for more features around this coming soon.

Popular projects on Code Climate

You might be interested in taking a look at:

How to add repositories

To add any Ruby app or library that is hosted in a public GitHub repository, visit the Add GitHub Repository page. Just provide the name of the repo (e.g. thoughtbot/paperclip) and your email address. Code Climate will clone the project, analyze it, and shoot you an email when the metrics are ready. This only takes a few minutes.

Matz has said he wants Ruby to be the “80% language”, the ideal tool for 80% of software development. After switching from TextMate to Sublime Text 2 (ST2) a few months ago, I believe it’s the “80% editor”. You should switch to it, especially if you’re using TextMate.

Why Sublime Text 2?

- Speed. It’s got the responsiveness of Vim/Emacs but in a full GUI environment. It doesn’t freeze/beachball. No need to install a special plugin just to have a workable “Find In Project” solution.

- Polish. Some examples: Quit with one keystroke and windows and unsaved buffers are retained when you restart. Searching for files by name includes fuzzy matching and directory names. Whitespace is trimmed and newlines are added at the end of files. Configuration changes are applied instantly.

- Split screen. I never felt like I missed this that much with TextMate, but I really appreciate it now. It’s ideal for having a class and unit test side-by-side on a 27-inch monitor.

- Extensibility. The Python API is great for easily building your own extensions. There’s lots of example code in the wild to learn from. (More about this later.) ST2 support TextMate snippets and themes out-of-the-box.

- Great for pair programming. TextMate people feel right at home. Vim users can use Vintage mode. When pairing with Vim users, they use command mode when they are driving. I just switch out of command mode and everything “just works”. (It also works on Linux, if that’s your thing.)

- Updates. This is mainly just a knock on TextMate, but it’s comforting to see new dev builds pushed every couple weeks. The author also seems to be quite responsive in the user community. A build already shipped with support for retina displays, which I believe is scheduled for a TextMate release in 2014.

Getting Started

I’ve helped a handful of new ST2 users get setup over the past few months. Here are the steps I usually follow to take a new install from good to awesome:

- Install the

sublcommand line tool. Assuming ~/bin is in your path:

ln -s "/Applications/Sublime Text 2.app/Contents/SharedSupport/bin/subl" ~/bin/subl

- It works like

mate, but has more options. Checksubl --help. - Install Package Control. Package Control makes it easy to install/remove/upgrade ST2 packages.Open the ST2 console with Ctrl+` (like Quake). Then paste this Python code from this page and hit enter. Reboot ST2. (You only need to do this once. From now on you’ll use Package Control to manage ST2 packages.)

- Install the Soda theme. This dramatically improves the look and feel of the editor. Use Package Control to install the theme:

* Press ⌘⇧P to open the Command Palette. * Select "Package Control: Install Package" and hit Enter. * Type "Theme - Soda" and hit Enter to install the Soda package.

- Start with a basic Settings file. You can use mine, which will activate the Soda Light theme. Reboot Sublime Text 2 so the Soda theme applies correctly. You can browse the default settings that ship with ST2 by choosing “Sublime Text 2” > “Preferences…” > “Settings – Default” to learn what you can configure.

- Install more packages. My essentials are SCSS, RSpec, DetectSyntax and Git. DetectSyntax solves the problem of ensuring your RSpec, Rails and regular Ruby files open in the right mode.

- Install CTags. CTags let you quickly navigate to code definitons (classes, methods, etc.). First:

$ brew install ctags - Then use Package Control to install the ST2 package. Check out the default CTags key bindings to see what you can do.

Leveling Up with Custom Commands

Sublime Text 2 makes it dead simple to write your own commands and key bindings in Python. Here are some custom bindings that I use:

- Copy the path of the current file to the clipboard. Source

- Close all tabs except the current one (reduces “tab sprawl”). Source

- Switch between test files and class definitions (much faster than TextMate). Source

- Compile CoffeeScript to JavaScript and display in a new buffer. Source

New key bindings are installed by dropping Python class files in ~/Library/Application Support/Sublime Text 2/Packages/User and then binding them from Default (OSX).sublime-keymap in the same directory. The ST2 Unofficial Documentation has more details.

Neil Sarkar, my colleague, wrote most of the code for all of the above within a few weeks of switching to ST2.

Running RSpec from Sublime Text 2

This is my favorite part of my Sublime Text 2 config. I’ll admit: Out of the box (even with the RSpec package installed), ST2 sucks for running tests. Fortunately, Neil wrote a Python script that makes running RSpec from Sublime Text 2 much better than running it from TextMate via the RSpec bundle.

With this script installed, you can bind ⌘R to run the current file and ⌘⇧R to run the current test. The tests will run in Terminal. This is great for a number of reasons:

- You can use any RSpec formatter and get nice, colored output.

- Adding calls to

debuggerorbinding.pryworks. No need to change how you run your tests when you want to debug. - Window management. It’s smart enough to reuse the Terminal window for new test runs if you don’t close it. I put my Terminal window on the right 40% of my monitor.

This has really improved my TDD workflow when working on individual classes.

More Resources

- Be sure to check out Brandon Keeper’s post on getting started with ST2.

- This article on NetTuts has some good tips. (Although it’s a little out of date.)

- My entire ST2 user directory is on GitHub, as is Neil’s.

- You can search for ST2 packages here. Don’t be afraid to dive into their source – it’s usually quite approachable.

If you’ve tried Sublime Text 2, what did you think? What packages, key bindings, etc. are your favorites? What do you miss most from other editors?

GORUCO 2012, NYC’s premier Ruby conference, is around the corner and it’s going to be great. (I may be biased, as I help organize the conference, but it’s still true!) We have some fantastic speakers this year, and I’m especially looking forward to three talks that focus on different aspects of code quality:

- “Maintaining Balance while Reducing Duplication – Part 2” by David Chelimsky. This is a follow up to David’s excellent talk from RubyConf 2010 that explored the DRY Principle (Don’t Repeat Yourself) in depth and illustrated how it can be misapplied. The inherent tensions between different OO design principles is particularly interesting to me.

- “Sensible Testing” by Justin Leitgeb. Justin really impressed me with his lightning talk at a recent NYC.rb about Ruby mixins and their problems. With this talk, I think he’ll do a great job exploring testing strategies for Rails apps in a practical, nuanced way. I wouldn’t be surprised if the Testing Pyramid comes up, which more developers should take to heart. TATFT is great mnemonic, but applying it well over a large codebase and a long period of time requires a great deal of consideration.

- “Hexagonal Rails” by Matt Wynne. Alistair Cockburn has been talking about Hexagonal Architecture (which he now calls “Ports and Adapters”) for years as a way to structure applications for better maintainability. It’s always been enticing to me, but it’s never been clear how to apply it to a Rails application. Matt has started exploring just that on his blog and I’m thrilled he’ll be giving a full-length talk on it at GORUCO. Personally, I hope he covers the implications on the model layer at least as much as controllers/views, and perhaps how this architecture might relate to the Anemic Domain Model antipattern described by Martin Fowler. (If not, I’ll ask him during Q&A. Hah.)

And before you ask, yes, the good folks at Confreaks will be recording the talks and we hope to have them posted within a few weeks of the conference (if not sooner).

If you’re attending GORUCO this year, definitely stop me and say “Hello!” (Either during the day, or aboard the ::ahem:: yacht during the evening.)

Full disclosure: I had the honor of being a member of the GORUCO Program Committee this year that selected the speakers, so it may not be a complete coincidence that my interests are well represented. 🙂

A common question teams run into while building a Rails app is “What code should go in the lib/ directory?”. The generated Rails README proclaims:

lib – Application specific libraries. Basically, any kind of custom code that doesn’t belong under controllers, models, or helpers. This directory is in the load path.

That’s not particularly helpful. By using the word “libraries” in the definition, it’s recursive. And what does “application specific” mean? Isn’t all the code in my Rails app “application specific” by definition?

So teams are left to work out their own conventions. If you quizzed the members of most teams, I’d bet they’d give different answers to the “What goes in lib/?” question.

Antipattern: Anything that’s not an ActiveRecord

As we know from the secret to Rails object oriented design, well crafted applications grow many plain old Ruby object that don’t inherit from anything (and certainly not the framework). However, the most common antipattern is pushing any classes that are not ActiveRecord models into lib/. This tremendously harmful to fostering a well designed application.

Treat non-ActiveRecord classes as first class citizens. Requiring these classes be stored in a lib/ junk drawer away from the rest of the domain model creates enough friction that they tend not be created at all.

Pattern: Store code that is not domain specific in lib/

As an alternative, I recommend any code that is not specific to the domain of the application goes in lib/. Now the issue is how to define “specific to the domain”. I apply a litmus test that almost always provides a clear answer:

If instead of my app, I were building a social networking site for pet turtles (let’s call it MyTurtleFaceSpace) is there a chance I would use this code?

Now things get easier. Let’s look at some examples:

- An

OnboardingReportclass goes inapp/. This depends on the specific steps the users must go through to get started with the application. - A

SSHTunnelclass used for deployment goes inlib/. MyTurtleFaceSpace needs to be deployed too. - Custom Resque extensions go in

lib/. Any site may use a background processing system. - A

ShippingRatesImportergoes inapp/if it imports a data format the company developed internally. On the other hand, aFedExRateImporterwould probably go inlib/. - A

GPGEncrypterclass goes inlib/. Turtles need privacy too.

Some developers find it distasteful to have classes like OnboardingReport and ShippingRatesImporter living in app/models/. This doesn’t bother me as I consider them to be part of the broadly defined “domain model”, but I’ll often introduce modules like Reports and Importers to group these classes which avoids them cluttering up the root of the app/models/ directory.

I’m sure there are other patterns for dividing code between lib/ and app/. What rule of thumb does your team follow? What are the pros and cons?