Leadership

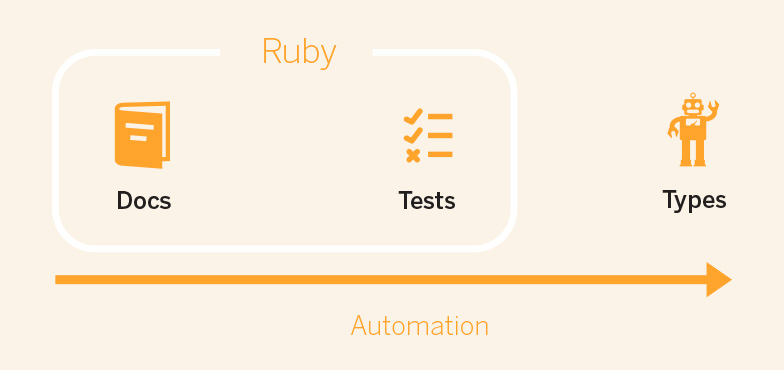

Ruby developers often wax enthusiastic about the speed and agility with which they are able to write programs, and have relied on two techniques more than any other to support this: tests and documentation.

After spending some time looking into other languages and language communities, it’s my belief that as Ruby developers, we are missing out on a third crucial tool that can extend our design capabilities, giving us richer tools with which to reason about our programs. This tool is a rich type system.

To be clear, I am in no way saying that tests and documentation do not have value, nor am I saying that the addition of a modern type system to Ruby is necessary for a certain class of applications to succeed – the number of successful businesses started with Ruby and Rails is proof enough. Rather, I am saying that a richer type system with a well designed type-checker could give our design several advantages that are hard to accomplish with tests and documentation alone:

- Truly executable documentation

Types declared for methods or fields are enforced by the type checker. Annotated classes are easy to parse by developers and documentation can be extracted from type annotations. - Stable specification

Tests which assert the input and return values of methods are brittle, raise confusing errors, and bloat test suites; documentation gets out of sync. Type annotations change with your implementation and can help maintain interface stability. - Meaningful error messages

Type checkers are valuable in part because they bridge the gap between the code and the meaning of a program. Error messages which inform you not only that you made a mistake, but how (and potentially how to fix it) are possible with the right tools. - Type driven design

Considering the design of a module of a program through its types can be an interesting exercise. With advancements in type checking and inference for dynamic programming languages, it may be possible to rely on these tools to help guide our program design.

Integrating traditional typing into a dynamic language like Ruby is inherently challenging. However, in searching for a way to integrate these design advantages into Ruby programs, I have come across a very interesting body of research about “gradual typing” systems. These systems exist to include, typically on a library level, the kinds of type checking and inference functionality that would allow Ruby developers to benefit from typing without the expected overhead. [1]

In doing this research I was pleasantly surprised to find that four researchers from the University of Maryland’s Department of Computer Science have designed such a system for Ruby, and have published a paper summarizing their work. It is presented as “The Ruby Type Checker” which they describe as “…a tool that adds type checking to Ruby, an object-oriented, dynamic scripting language.” [2] Awesome, let’s take a look at it!

The Ruby Type Checker

The implementation of the Ruby Type Checker (rtc) is described by the authors as “a Ruby library in which all type checking occurs at run time; thus it checks types later than a purely static system, but earlier than a traditional dynamic type system.” So right away we see that this tool isn’t meant to change the principal means of development relied on by Ruby developers, but rather to augment it. This is similar to how we think about Code Climate – as a tool which brings information about problems in your code earlier in your process.

What else can it do? A little more from the abstract:

“Rtc supports type annotations on classes, methods, and objects and rtc provides a rich type language that includes union and intersection types, higher- order (block) types, and parametric polymorphism among other features.”

Awesome. Reading a bit more into the paper we see that rtc operates by two main mechanisms:

- Compiling field and method annotations to a data structure that is later used for checks

- Optionally proxying calls through a system that gathers type information, allowing type errors to be raised on method entry and exit

So now let’s see how these mechanisms might be used in practice. We’ll walk through the ways that you can annotate the type of a class’s fields, and show what method type declarations look like.

First, field annotations on a class look like this:

class Foo typesig('@title: String') attr_accessor :title end

And method annotations should look familiar to you if you’ve seen type declarations for methods in other languages:

class Foo typesig("self.build: (Hash) -> Post") def self.build(attrs) # ... method definition end end

Where the input type appears in parens, and then the return type appears after the -> arrow that represents function application.

Similar to the work in typed Clojure and typed Racket (two of the more well-developed ‘gradual’ type systems), rtc is available as a library and can be used or not used a la carte. This flexibility is fantastic for Ruby developers. It means that we can isolate parts of our programs which might be amenable to type-driven design, and selectively apply the kinds of run time guarantees that type systems can give us, without having to go whole hog. Again, we don’t have to change the entire way we work, but we might augment our tools with just a little bit more.

How Would We Use Gradual Typing?

Asking the following question on Twitter got me A LOT of opinions, perhaps unsurprisingly:

What are the canonical moments of “Damn, I wish I had types here?” in a dynamic language?— mrb (@mrb_bk) April 29, 2014

The answers ranged from “never” to “always” to more thoughtful responses such as “during refactoring” or “when dealing with data from the outside world.” The latter sounded like a use case to me, so I started daydreaming about what a type checked model in a Rails application would look like, especially one that was primarily accessed through a controller that serves a JSON API.

Let’s look at a Post class:

class Post include PersistenceLogic attr_accessor :id attr_accessor :title attr_accessor :timestamp end

This post class includes some PersistanceLogic so that you can write:

Post.create({id: "foo", title: "bar", timestamp: 1398822693})

And be happy with yourself, secure that your data is persisted. To wire this up to the outside world, now imagine that this class is hooked up via a PostsController:

class PostsController def create Post.create(params[:post]) end end

Let’s assume that we don’t need to be concerned about security here (though that’s something that a richer type system can potentially help us with as well). This PostsController accepts some JSON:

{ "post": { "id": "0f0abd00", "title": "Cool Story", "timestamp": "1398822693" } }

And instead of having to write a bunch of boilerplate code around how to handle timestamp coming in as a string, or title not being present, etc. you could just write:

class Post rtc_annotated include PersistenceLogic typesig('@id: String') attr_accessor :id typesig('@title: String') attr_accessor :title typesig('@timestamp: Fixnum') attr_accessor :timestamp end

Which might lead you to want a type-checked build method (rtc_annotatetriggers type checking on a specific object instance):

class Post rtc_annotated include PersistenceLogic typesig('@id: String') attr_accessor :id typesig('@title: String') attr_accessor :title typesig('@timestamp: Fixnum') attr_accessor :timestamp typesig("self.build: (Hash) -> Post") def self.build(attrs) post = new.rtc_annotate("Post") post.id = attrs.delete(:id) post.title = attrs.delete(:title) post.timestamp = attrs.delete(:timestamp) end end

But, oops! When you run it you see that you didn’t write that correctly:

[2] pry(main)> Post.build({id: "0f0abd00", title: "Cool Story", timestamp: 1398822693}) Rtc::TypeMismatchException: invalid return type in build, expected Post, got Fixnum

You can fix that:

class Post rtc_annotated include PersistenceLogic typesig('@id: String') attr_accessor :id typesig('@title: String') attr_accessor :title typesig('@timestamp: Fixnum') attr_accessor :timestamp typesig("self.build: (Hash) -> Post") def self.build(attrs) post = new.rtc_annotate("Post") post.id = attrs.delete(:id) post.title = attrs.delete(:title) post.timestamp = attrs.delete(:timestamp) post end end

Okay let’s run it with that test JSON:

Post.build({ id: "0f0abd00", title: "Cool Story", timestamp: "1398822693" })

Whoah, whoops!

Rtc::TypeMismatchException: In method timestamp=, annotated types are [Rtc::Types::ProceduralType(10): [ (Fixnum) -> Fixnum ]], but actual arguments are ["1398822693"], with argument types [NominalType(1)<String>] for class Post

Ah, there ya go:

class Post rtc_annotated include PersistenceLogic typesig('@id: String') attr_accessor :id typesig('@title: String') attr_accessor :title typesig('@timestamp: Fixnum') attr_accessor :timestamp typesig("self.build: (Hash) -> Post") def self.build(attrs) post = new.rtc_annotate("Post") post.id = attrs.delete(:id) post.title = attrs.delete(:title) post.timestamp = attrs.delete(:timestamp).to_i post end end

So then you could say:

Post.build({ id: "0f0abd00", title: "Cool Story", timestamp: "1398822693" }).save

And be type-checked, guaranteed, and on your way.

Just a Taste

The idea behind this blog post was to get Ruby developers thinking about some of the advantages of using a sophisticated type checker that could programmatically enforce the kinds of specifications that are currently leveraged by documentation and tests. Through all of the debate about how much we should be testing and what we should be testing, we have been potentially overlooking another very sophisticated set of tools which can help augment our designs and guarantee the soundness of our programs over time.

The Ruby Type Checker alone will not give us all of the tools that we need, but it gives us a taste of what is possible with more focused attention on types from the implementors and users of the language.

Works Cited

[1] Gradual typing bibliography

[2] The ruby type checker [pdf]

Editor’s Note: Our post today is from Peter Bell. Peter Bell is Founder and CTO of Speak Geek, a contract member of the GitHub training team, and trains and consults regularly on everything from JavaScript and Ruby development to devOps and NoSQL data stores.

When you start a new project, automated tests are a wonderful thing. You can run your comprehensive test suite in a couple of minutes and have real confidence when refactoring, knowing that your code has really good test coverage.

However, as you add more tests over time, the test suite invariably slows. And as it slows, it actually becomes less valuable — not more. Sure, it’s great to have good test coverage, but if your tests take more than about 5 minutes to run, your developers either won’t run them often, or will waste lots of time waiting for them to complete. By the time tests hit fifteen minutes, most devs will probably just rely on a CI server to let them know if they’ve broken the build. If your test suite exceeds half an hour, you’re probably going to have to break out your tests into levels and run them sequentially based on risk – making it more complex to manage and maintain, and substantially increasing the time between creating and noticing bugs, hampering flow for your developers and increasing debugging costs.

The question then is how to speed up your test suite. There are a several ways to approach the problem. A good starting point is to give your test suite a spring clean. Reduce the number of tests by rewriting those specific to particular stories as “user journeys.” A complex, multi-page registration feature might be broken down into a bunch of smaller user stories while being developed, but once it’s done you should be able to remove lots of the story-specific acceptance tests, replacing them with a handful of high level smoke tests for the entire registration flow, adding in some faster unit tests where required to keep the comprehensiveness of the test suite.

In general it’s also worth looking at your acceptance tests and seeing how many of them could be tested at a lower level without having to spin up the entire app, including the user interface and the database.

Consider breaking out your model logic and treating your active record models as lightweight Data Access Objects. One of my original concerns when moving to Rails was the coupling of data access and model logic and it’s nice to see a trend towards separating logic from database access. A great side effect is a huge improvement in the speed of your “unit” tests as, instead of being integration tests which depend on the database, they really will just test the functionality in the methods you’re writing.

It’s also worth thinking more generally about exactly what is being spun up every time you run a particular test. Do you really need to connect to an internal API or could you just stub or mock it out? Do you really need to create a complex hairball of properly configured objects to test a method or could you make your methods more functional, passing more information in explicitly rather than depending so heavily on local state? Moving to a more functional style of coding can simplify and speed up your tests while also making it easier to reason about your code and to refactor it over time.

Finally, it’s also worth looking for quick wins that allow you to run the tests you have more quickly. Spin up a bigger instance on EC2 or buy a faster test box and make sure to parallelize your tests so they can leverage multiple cores on developers laptops and, if necessary, run across multiple machines for CI.

If you want to ensure your tests are run frequently, you’ve got to keep them easy and fast to run. Hopefully, by using some of the practices above, you’ll be able to keep your tests fast enough that there’s no reason for your dev team not to run them regularly.