docs/Code-Reviews.mdx

import { Meta } from '@storybook/blocks';

<Meta title="docs/Code-Reviews" />

# Helpful code reviews

This document presents some of the principles behind how and why we do code reviews, as well as collecting some useful bits of advice to make code reviews more effective and enjoyable for everyone.

It is not meant to be an exhaustive guide to carrying out reviews - there are already many online resources on this subject. This document incorporates some of their ideas (especially from Gergely Orosz’s excellent [Good Code Reviews, Better Code Reviews](https://blog.pragmaticengineer.com/good-code-reviews-better-code-reviews/)) but expands on a few topics of particular importance for our teams.

## Why review code?

Reviewing code can sometimes help to catch bugs earlier in the development life cycle when [they *may* be cheaper to fix](http://thklein.com/cost-of-defect/). Even then, it is not realistic to expect most defects to be caught this way. In large, distributed teams like ours, the main objective of code reviews is *communication*.

Code reviews are an indispensible tool for spreading knowledge and ideas between teams. A [2013 study at Microsoft](https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/expectations-outcomes-and-challenges-of-modern-code-review/) found that while ‘finding defects’ was the most commonly-given reason for doing code reviews, the most frequent actual outcomes were sharing understanding and introducing other types of code improvement. Communication in code review can take many forms: from an ‘FYI’, to sharing new approaches and best practices, to improving documentation and code readability (communicating to future developers).

Our primary aim in participating in code reviews is to learn from each other, increasing our understanding of the codebase we are responsible for and of the technologies we use.

## Who reviews?

All developers in our teams, regardless of the level of experience, give and receive code reviews as part of their day-to-day work. In general, for junior developers, code reviews are an opportunity to ask questions and learn. More senior developers can use it as a tool for coaching and encouraging others. But these roles are fluid - many experienced developers have had problems pointed out to them by newcomers with a good eye for inconsistency. Everybody can contribute something.

We believe that being able to review code effectively is a vital part of any software engineer's skills, just as important as writing code. And like any other skill it requires practice.

**Approvals**

GitHub supports the concept of 'approvals'. Our repos generally require **two** approving reviews before a change can be merged on GitHub. Approvals should usually come from people who were not directly involved in implementing the change.

* Anyone can approve a PR, regardless of seniority or experience

* Approving a PR does not mean that it cannot be improved upon in some way

* Similarly, approving a PR does not mean you will be held personally responsible for it

* If problems are found later, we'll fix them together, work out what went wrong and try to do better next time.

## Our approach to reviewing code

Code reviews are not an exercise in scoring points or proving that the reviewer knows better than the author - they are about trying to help each other to make the best quality work we can. Ideally, both author and reviewer come away from a code review having both made a positive contribution to the result and learned something along the way.

Software development is a collaborative process. We own the whole codebase collectively across our teams. Nobody has one special responsibility or authority over any one part of it. Feedback on code should never feel personal but should always be directed at improving our solutions and how we work together.

Whatever problems we may find as we explore and discuss code, we assume that everyone is (and was) acting with best intentions, based on what they knew at the time and under circumstances that are often lost to us. Instead of complaining, we propose concrete steps we can take to make things better.

## How long should it take?

Although we value code review highly for the reasons given above, we also recognise that we have limited time and resources and a long list of work to complete. Time spent on code review should be kept in proportion with other stages of the development life cycle including testing and accessibility and UX review.

The amount of time spent on code review will vary from task to task, but as a rule of thumb, if a PR has been at the code review stage for longer than it was in the initial implementation, it has been there too long. Both authors and reviewers have a shared responsibility to ensure that code review is completed in a timely fashion.

We strive for quality but we do not aim for perfection ('perfect' code does not exist anyway!).

## Reducing the effort needed in code review

Pair programming and swarming/mobbing during the implementation phase are approaches that can reduce the time spent on lengthy in-depth code reviews later on, because more of the necessary communication has already happened. More people contributing to the solution may help to catch some types of issues before code review. Seeking alignment through early collaboration can therefore minimise the back-and-forth sometimes seen in code reviews.

These collaboration techniques can be especially useful when there's a high degree of unfamiliarity - in the work, the tech or individuals in the team.

## If you need a review

If it’s your first experience of code review, don’t worry. Getting used to having your work looked at by others is an important step. Expect some questions and some suggestions, but it’s not meant personally. Your colleagues will be happy to explain anything that is unclear. They want to help you succeed.

There are some simple things you can do that will make it easier for someone to review your code. Remember to check:

* Have you linked to the GitHub issue that describes the problem you were trying to solve/feature you were trying to build? If there isn't one, create it - often taking a few minutes to summarise the requirement and a ‘definition of done’ can help avoid oversights in the implementation.

* If you can't, or the change is so trivial it's unnecessary, say "no issue" (but ensure the requirements are clearly described on the PR).

* Could the change be broken down into smaller PRs that can be reviewed separately/in parallel? A common, quite reasonable reaction from a reviewer to a PR that changes many hundreds of lines of code is, "This is a big one! I'll do it later when I have more time." Shorter PRs often get attention quicker because they are simpler to understand and therefore review.

* Does the PR have a clear and succinct title? This will help people quickly understand the aim of the change when looking at lists of PRs

* Have you included a more detailed summary of the code changes made (and why) along with any additional context that would help a reader? Making life as easy as possible for the reviewer will probably mean the PR gets reviewed faster. Things to consider include:

* Useful links (e.g. test URLs, links to relevant parts of API documentation)

* Related PRs or other work for comparison

* Screenshots (these often paint a thousand words)

* Have you completed the PR checklist in full? If there are items you're not sure about, leave a comment next to them so the reviewer knows you haven't just ignored them.

**Responding to comments**

Just as with receiving any feedback, having comments made on your work can sometimes be challenging. This is a normal human reaction and can affect engineers at all stages of their careers.

Some things to consider when responding to code reviews:

* We can all feel quite attached to code we write, but try taking a step back and not being protective of your particular solution.

* Try to understand the views of the person who has written the comment - it might mean additional work, but could their suggested change help in the long run?

* Have patience in answering questions and explaining your thought processes. Reviewers may be missing some context or not understand why you arrived at your solution.

* Give the other person the benefit of the doubt. Sometimes suggestions can sound blunt when written in text. Rather than replying directly, it may help to suggest a call to talk it through.

If using GitHub PRs, allow the original commenter click ‘Resolve conversation’ when required. The author should check in with the reviewer if a conversation has not been resolved before doing so.

## If you are reviewing someone else's code

If you're new to the codebase or looking at a new area of it, consider the following tips as a good place to start doing a code review.

**Understand the context**

Check if there is a linked issue/ticket in the pull request that contains some acceptance criteria, a definition of done, or at least a description of what the output of the work should be. Then read through the summary of code changes to get a high-level understanding of the solution. If any of this information is missing then ask the author to provide it.

**Check it out**

Do check out the code and run it locally if possible. This can help to better understand what the change is doing. It can also help to find bugs early before any formal testing is carried out.

**Seek clarification**

If there’s something you don’t understand or that seems unexpected in the PR, ask the author to clarify. Many disagreements in code review come down to misunderstandings - either the author(s) did not fully understand the requirements, or the reviewer does not follow the author's reasoning.

If information gained at this stage might be helpful for future maintainers of the code, think about whether it could be preserved in the form of documentation as part of this or a follow-up PR.

**Ask questions**

As already mentioned, code reviews are a great way to learn about the codebase and technology generally. **There are no stupid questions.** If you’re wondering about it, someone else probably is too.

Another way reviewers can use questions is to ensure that we have considered the problem from all the angles. Code review is a good time to think again about performance, security, accessibility, testing and other [non-functional requirements](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-functional_requirement) that might have been overlooked. For example:

* Is this going to be accessible to all users?

* Would it be a good idea to run some performance/load tests on this?

* Is there a plan to add or update the documentation?

* What additional test coverage might be needed? (e.g. end-to-end tests)

**Chat about it**

Adding comments on GitHub PRs is often the default way of conducting code reviews, but it’s not always the most efficient when we have other communication tools at our disposal. Often the quickest and most effective way to ask complex questions about a PR or respond to feedback is by suggesting a call at a convenient time.

If you can see comments going back and forth on a PR, it might be time to suggest a call. Even better, if you have left a lot of comments on a PR, proactively reach out to the author to suggest a call.

Share the call link on any relevant Slack channels so that others can contribute or listen in - this is particularly helpful for remote-oriented teams where the opportunities to overhear an interesting discussion can be lost.

One person can be nominated to write a short summary of the conversation and add it to the PR after the call to preserve any insights or decisions that were reached.

**Be kind**

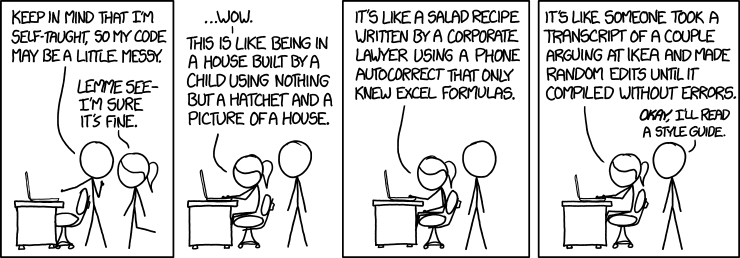

When carrying out code reviews we should always be empathetic towards the other person. Authors have often put a lot of work into their code. A [positive and constructive tone](https://blog.pragmaticengineer.com/good-code-reviews-better-code-reviews/#tone-of-the-review) helps to create a better environment for everyone. Remember that not everyone arrives at software engineering by the same route - what may seem elementary to you may be new to someone else.

Particular care should be taken if the author is a new contributor who might be unfamiliar with the codebase/our approach. While maintaining our high standards, we should work extra hard to ensure their experience of having their first efforts reviewed is a positive one that leaves them wanting to contribute again.

**Pair and swarm**

Reviewing is sometimes easier if you do it together. Find another developer to pair with on the review - this could be someone more familiar with the code being changed, but it doesn't have to be. Compare your observations and discuss your ideas together before one person adds comments to the PR.

*Swarm reviews* involving a larger group of reviewers can also be effective, especially for more complex pieces of work. The author should join the review too - this is so they can answer clarifying questions asked by the reviewers, explain context behind the work and the approach taken. Having a person who isn’t an author ‘lead’ swarm reviews can be useful - they can share their screen as they look at the PR and think aloud whilst reviewing the work. It is especially helpful when the lead reviewer in the swarm is the person who is least familiar with the code - they can ask lots of questions

**Automate it!**

Linting code is a job for robots. If you find yourself pointing out the same things over and over again, think about whether that could be implemented as a linter rule, or some other kind of automated check. That way future reviews will be easier and more consistent.

**Offer links and examples**

When referring to an established idea or technique, link to a page that explains it succinctly. Better still, find an example in the codebase (or another familiar codebase) to link to. Offer such alternatives without insisting upon them. They may have already been considered and discounted for good reason.

If you are proposing a specific code change, try to give enough information for the author to understand it and implement it if needed. Direct GitHub PR ‘suggestions’ are often welcomed by authors - but consider if it would still help to explain *why* you’re suggesting the change.

Failing this, adding a small pseudo-code fragment is often a great way to illustrate the idea.

**Go beyond LGTM**

When approving a simple PR, the classic *looks good to me* is sometimes enough, but the best reviews are more than a rubber stamp. For example, you can include a description of what you did to verify that the change was correct (again, screenshots may save typing) that can be repeated by others. Or, you can applaud anything about the work you thought that was particularly good so the author knows it’s worth doing next time.

**Be flexible**

Sometimes serious issues are found during code review that need to be addressed before the change can be merged. But often this is not the case. Ask, could the code be merged without addressing these comments? If it can, create follow-up tasks that can be picked up afterwards and link them to the PR. It’s often quicker and more effective for reviewers to create these tasks.

**Take care with evaluations**

It's important to remember that many labels given to code are subjective, or at least have no universally agreed meaning. Often they depend heavily on the context of the work as well as each developers’ background and stylistic preferences. Remember that no two developers will ever solve any non-trivial problem the same way.

One person’s *explicit* may be too *verbose* for others. *Consistency* is often prized, but when does it become *repetitious?* A suggestion to make something more *concise* might come at the expense of making it *less readable* for some. How *clean* is clean?

Such evaluations have their uses, but we should recognise them for what they are, and when making them consider that other points of view may be possible. Often there is no quick way to resolve these dilemmas other than to simply talk it through.

Above all, reviewers should avoid just saying that they don’t like something with only vague justifications or without offering any alternatives.

**Avoid perjorative jargon**

Not everyone knows (or agrees) what a ‘code smell’ or an ‘antipattern’ is. If you find yourself reaching for these labels, consider instead if you can articulate more objectively what problems you foresee. This will help the author understand your point of view better, and also improve their own knowledge.

## Conclusion

In brief, code reviews exist to support communication as we work together on the codebase. Remembering to see others’ perspectives when reviewing code creates a more positive environment for everyone. Remember to talk - back-and-forth PR comments are usually not the most effective way of having a conversation. And pairing and swarming can help to make the process easier - both during implementation and at the review stage.