Leadership

Every day, engineering leaders ask their team members the same three standup questions to ensure the software development engine hasn’t come to a complete stop. It’s excruciatingly boring to be asked the same questions day in and day out, and it’s not a productive use of engineers’ time. These questions — the “are things moving?” questions — can be answered with the help of a Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) solution, like Code Climate, freeing up valuable standup time for an even more impactful set of questions, the “how can we move faster?” questions. These are the questions that dig deeper into a team’s processes and practices, helping leaders identify opportunities for improvement and drive excellence on their teams.

In this two-post series, I’ll explain how data can help you answer the classic standup questions, then walk through the “next three questions,” that every engineering leader should be asking to level up their standups — and level up their team.

First, the classic questions:

- What did you do yesterday?

- What will you do today?

- What (if anything) is blocking your progress?

Let’s dig in.

Standup questions one and two: What did you do yesterday? What will you do today?

These questions are meant to help you understand what progress your team has made so far, so you can assess your team’s output within the context of your current sprint or cycle. In comparing what’s been done so far to what’s planned, you can get a sense of the sprint’s status.

Rather than ask your developers for a rundown of yesterday’s completed tasks and today’s to-do list, let the data speak for itself. You could do this by running a Git diff for every branch, or you could let Code Climate's SEI platform do the work, drawing connections between Commits and Issues and providing an accurate view of what your team is working on. This can also help you check that the team is prioritizing appropriately, and working on the most impactful Issues. You can also review the Issues that have yet to be started to determine whether the team is saving the trickier work for last. This isn’t necessarily a problem, but it could indicate that a slowdown is to come, and may be worth discussing during standup.

Of course, data won’t tell you for sure whether your team will hit its deadline, but it will give you a big picture view of how your sprint is progressing and where the team might need your help.

Standup question three: What (if anything) is blocking your progress?

Once you have a high-level understanding of the progress of your current iteration, you’ll want to know if there’s anything that might throw it off track. Developers might be hesitant to call out blockers, preferring instead to solve problems themselves, or they may lack the context to foresee potential slowdowns. Data addresses both of those problems, though the relevant information has historically been harder to find, as it’s spread throughout your VCS and project management tools. This is where a Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) solution is particularly valuable — Code Climate can even send you a customized alert when a particular unit of work is stuck or at risk.

Work that is stuck may have gone a few days without a Commit, or may be marked “In Progress” in Jira for an atypical length of time. Work that is at risk is work that is not moving through the software development pipeline as expected, and which may become a bottleneck if not addressed. Though the signs of risk vary from team to team, Pull Requests with high levels of Rework, or many comments or Review Cycles are worth further investigation, as are PRs that haven’t been picked up for review in a timely fashion.

Data can also help you identify possible blockers in developers’ collaboration patterns. Every engineer will have their own opinion of how the team is working, and though it’s important to understand how engineers are feeling about the current state of collaboration on the team, it’s critical to check any hidden biases with objective data.

Start by looking at the distribution of work across the team. Is there someone who is overloaded, or someone who isn’t getting work? Code Climate makes this easy with a Work in Progress metric that tells you how much each engineer is working on at a given time. Then, to get a sense of the team’s broad collaboration patterns, it can be helpful to determine how many engineers are working on the same Issue or Pull Request. This way, you can be aware of a possible “too many cooks” situation, or dependencies that may impact delivery.

So, what standup questions should you be asking instead?

When you enter standup with this information, you can skip past the classic three standup questions in favor of three more impactful questions:

- How can I help remove distractions?

- How can the team help resolve that risk?

- Are we working on the right things (see what people are working on, blend that with your context)?

The answers to these questions will help you move beyond a short-term focus on getting work done and help you get to the next level, where you’re focused on helping your team excel. Find out how in my next post.

This is the first post in a two-part series. Read the second post here.

Engineering metrics can be a powerful tool for tracking and communicating engineering progress, debugging processes, boosting team performance, and much more – but they must be wielded with care. When misused, metrics can backfire, creating confusion and resentment.

To help engineering leaders successfully leverage metrics, Code Climate has partnered with LeadDev on a series of blog posts and webinars that explore the fundamentals of data-driven leadership. Drawing on the expertise of engineering leaders from a range of industries, we highlight real-world perspectives on the what, why, and how of measuring as an engineering leader. We touch on everything from selecting the best metrics to track for your organization, to introducing metrics successfully, and specific use cases, like using metrics to run more impactful standups.

Here are some key insights:

- “I’ve found that metrics are valuable in helping zero in on what might be getting in the team’s way. Instead of treating them as a way to judge performance, I believe metrics are most useful in bringing to light areas of opportunity.” Leslie Cohn-Wein, Engineering Manager, Netlify

- “First and foremost, I use metrics to help me identify what the biggest bottlenecks are across different teams. Without metrics, I’d be left to make this judgment based on hearsay instead of methodology. The second reason I use metrics is to understand changes over time, particularly as we undergo organizational changes or make investments in specific areas.” Abi Noda, Developer Experience Expert

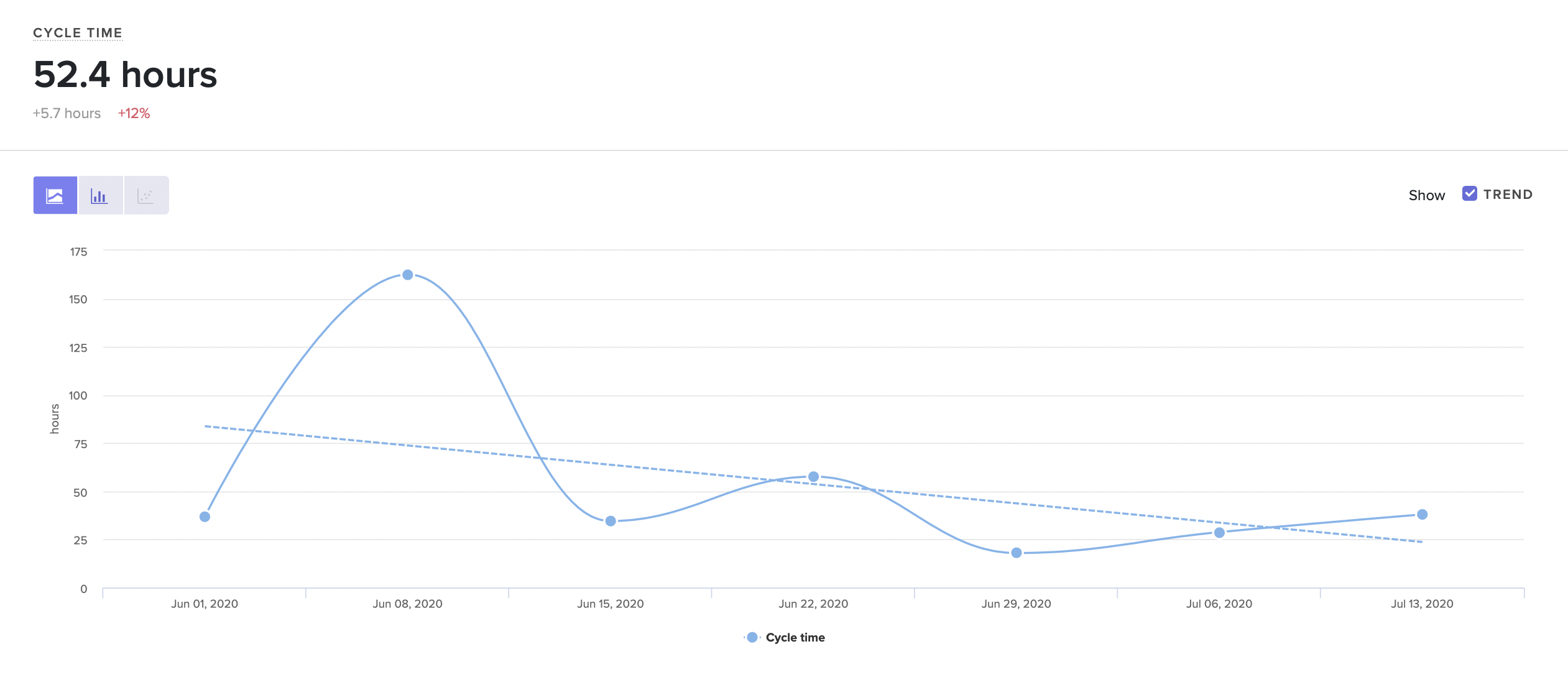

- “Cycle Time is a metric that I consistently come back to — it’s a great proxy for engineering speed, and can be a useful high-level look at whether certain key decisions are having the desired impact. If we’re moving slower than we had been, I can then isolate parts of the engineering pipeline and investigate where exactly things are going off track.” James McGill, VP of Engineering, Code Climate

- “The outcomes of productive standups ripple throughout the engineering team. By discussing specific metrics in standups, you can tell if your team is moving forward. You can ensure that the risks are being addressed from an objective, quantifiable standpoint rather than opinion.” Khan Smith, VP of Product, Code Climate

To dig deeper into what engineering leaders are doing today with metrics, check out the full series.

Ready to get started with engineering metrics in your organization? Contact our product specialists.

A good leader can respond to issues and course correct in the moment, but a great leader is proactive about staying ahead of the curve. With the help of data provided by Engineering Intelligence tools, an Engineering Manager can gain visibility into the development pipeline and stay equipped with the knowledge needed to cut problems off at the pass. No matter where an EM is in their professional lifecycle, a proactive one can prioritize more successfully, strengthen coaching strategies, and boost team effectiveness in the short term, mid-term, and long term.

Short Term Strategy: Spot Risk and Prevent Blockages

A lot of dedication goes into keeping sprints on track and software delivery on schedule. With so many moving parts in the development pipeline, an EM may find it tough to determine what needs their attention first, making it challenging to triage risks. However, by using a Software Engineering Intelligence platform — like Code Climate — that conveys insights based on aggregated data, an EM can swiftly analyze coding progress and prioritize their task list to focus on what’s most important.

For example, an EM can assess PR and Commit data to surface at-risk work — work that could benefit from their time and attention. If a Commit has had several days of inactivity and work on the associated PR has seemingly halted, it may indicate that the scope of the task is not clear to ICs, and that they require guidance. Or it may be a sign of task-switching, where too much Work In Progress pulls an IC’s focus and makes it difficult to complete work.

This is where data from a Software Engineering Intelligence platform is critical, as it can signal to a manager that a specific PR or Issue needs attention. Code Climate enables EMs to set Risk Alerts for PRs based on custom criteria, since risk thresholds vary from team to team. From there, the EM can use that information in standups, retros, and other conversations with ICs to help identify the root cause of the blocker and provide coaching where needed.

Mid-term Strategy: Improve Collaboration

As a proactive leader, an EM must understand the nuances of collaboration between all parties to ensure ICs and teams are working together effectively and prioritizing issues that are aligned with company goals. If teams fail to work cohesively, roadmaps may be thrown off course, deadlines may be missed, and knowledge silos may be created. Using their Engineering Intelligence tools, an EM can easily surface the quantitative data needed to gain visibility into team collaboration and interdepartmental alignment.

When it comes to collaboration on their team, an EM might want to look at review metrics, like Review Count. Viewing the number of PRs reviewed by each contributor helps an EM understand how evenly reviews are distributed amongst their team. Using these insights, a manager can see which contributors are carrying out the most reviews, and redistribute if the burden for some is too high. Doing so will not only help keep work in balance, but the redistribution will expose ICs to different parts of the codebase and help prevent knowledge silos.

To look at collaboration between teams, an EM can rely on quantitative data to help surface signs of misalignment. Looking at coding activity in context with information from Jira can help an EM identify PRs that signal a lack of prioritization, such as untraceable or unplanned PRs. Since these PRs are not linked back to initial project plans, it may indicate possible misalignment.

Long Term Strategy: Support Professional Growth and Improve Team Health

A proactive EM also needs to identify struggling IC’s, while simultaneously keeping high performers engaged and challenged to prevent boredom. This starts with understanding where each individual IC excels, where they want to go, and where they need to improve.

Using quantitative and qualitative data, an EM can gain a clearer understanding of what keeps each IC engaged, surface coaching opportunities, and improve collective team health. Qualitative data on each IC’s coding history — Commits, Pushes, Rework, Review Speed — can help signal where an IC performs well and surface areas where it might be useful for an EM to provide coaching. An EM can then use qualitative data from 1 on 1’s and retros to contextualize their observations, ask questions about particular units of work, or discuss recurring patterns.

For example, if an EM notes high levels of Rework, this signals an opportunity to open up a meaningful discussion with the IC to surface areas of confusion and help provide clarity. Or, an EM might see that an IC has infrequent code pushes and can coach the IC on good coding hygiene by helping them break work down into smaller, more manageable pieces that can be pushed more frequently.

Using a combination of both data sets, a manager can initiate valuable dialogue and create a professional development roadmap for each IC that will nurture engagement and minimize frustration.

Proactivity as an EM – The Long and Short of It

Proactivity is a skill that can be developed over time and enhanced with the help of data. Once empowered with the proper insights, EMs can more effectively monitor the health of their sprints, meet software delivery deadlines, keep engineers happy, and feel confident that they are well-informed and can make a marked, positive impact.

In the classic standup meeting, the onus is on individual contributors to come prepared. Questions are asked of the group — questions like “what are you working on?”, and “what blockers are you facing?” — and each team member has a turn to answer. Though this approach is theoretically designed to help facilitate alignment and detect possible issues before they derail sprints, it often results in non-engaging, ineffective meetings.

It’s not enough for a manager to pose broad questions and expect ICs to come prepared to discuss their work. To run a truly impactful standup, the expectation needs to be flipped. To ensure an engaging, high-value meeting, the Engineering Manager is the one who needs to show up prepared.

It’s Not Reasonable to Expect ICs to Surface All Potential Issues

When an IC is engaged with their work and invested in the outcome, it should be easy for them to show up at standup and give a status update. It’s getting to the next level that’s often difficult.

Even when you’ve done the work to foster psychological safety on your team, developers may still be hesitant to surface an issue or ask questions in a public forum. It’s not necessarily that they fear punishment or don’t want to appear uninformed — they may simply want the satisfaction of solving a tough problem before they share it with the team. Or, they may lack the context to realize that their teammates are working on a similar problem and that all of them would benefit from some discussion and collaboration.

And in the most blameless of cultures, where a developer feels comfortable flagging an issue or asking a question about their own work, it’s likely that same developer will hesitate to publicly bring up an issue that directly involves a teammate, for fear of being seen to call that teammate out.

Why it’s Critical for Engineering Managers to Show up for Standups Prepared

When an Engineering Manager walks into standup prepared, they can help guide their team past surface-level updates, towards higher-value conversations. A prepared manager has context — they understand how units of work fit together, and know when a team member’s work has critical downstream impacts, or when one developer has previously worked through an issue similar to one that another developer is struggling with.

With that perspective, it’s possible to make connections and facilitate conversations and collaboration. In a typical standup, a team member might just say they’re almost ready to ship a particular feature. Yet if the Engineering Manager comes prepared to that same standup, they’ll be able to have more informed conversations about the work. They might note that the developer’s work bounced back and forth in Code Review more than normal, and ask them if it would be helpful to take a step back and review the architecture. Or, they may flag an uptick in Rework, prompting the developer to volunteer that they’re working through a bug, and opening up an opportunity to pair them with a teammate who recently had a similar issue.

The information Engineering Managers need to prepare for standup is already there, in their VCS and project management tools. A Software Engineering Intelligence platform can help make it more accessible, pulling together data on everything from Code Review to Rework, and highlighting Pull Requests that aren’t moving through the development pipeline as expected.

If Engineering Managers take the time to review that data and gain context before standup, they’ll be able to help their team skip past the status update and spend their valuable meeting time having more impactful conversations — conversations that not only help move the work forward, but which improve alignment, foster collaboration, and help their team excel.

Standups should be a vital ceremony for building trust and cohesion within a team. They’re meant to help your team remain engaged and adaptable, so they can keep work moving forward.

The reality is, most standups do none of that.

It’s not that standups aren’t a good idea in theory; teams should have a regular touchpoint that enhances collaboration and alignment. In practice, however, they fall flat. Too often, standups are held simply because they’re expected — they’re a cornerstone of agile, after all — not because they provide value to the team. They’re frequently maligned as boring and ineffective.

Like all processes that exist because of a shared understanding of how things “should” be, standups are in need of an overhaul.

To add value back into your standups, focus on the reason you’re holding them in the first place. Foreground those goals (alignment, adaptability, and engagement), and think about the particular dynamics of your team. How can you encourage your team members to contribute in a meaningful way, and to help fulfill the goals of the standup?

Every team is different, which means every answer will be slightly different. You’ll likely have to iterate before you land on a process that works for your team. And you’ll have to continue to iterate as your team and its needs change.

That said, there are a few broad strategies we here at Code Climate recommend:

Keep key questions at the forefront – Once you’ve decided on the critical questions that every standup needs to answer, make sure that information stays top of mind for all involved. We recommend pasting these questions into the standup calendar invite and revisiting them at the beginning of every standup, so they serve as a constant reminder to attendees and help keep conversations focused. The key questions we ask are:

- What did you work on yesterday?

- What are you working on today?

- Are you blocked on anything?

Don’t be afraid to ask follow up questions too, as long as they help further the goals for your meeting.

Prepare with data – To be impactful, standups need to surface the units of work most in need of attention and discussion. While you should create an environment that will encourage your team members to speak up when they need help, it’s not a guarantee that they will. A Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) platform like Code Climate can help you spot bottlenecks and identify at-risk work, so you can walk into standups prepared. If your team members raise those issues, you’ll be ready to offer guidance. If they don’t, you can raise them yourself and help troubleshoot so that the sprint stays on track.

Create a blameless space – Ensure your team members understand that they won’t be penalized for raising an issue or voicing a concern. This will help create a feeling of safety — when engineers know they won’t be punished for it, they’ll be more likely to surface potential problems and ask for help.

Leave time for hesitation – Before moving on to the next person or topic, leave a moment of pause. Sometimes there’s an impulse to move through standup as fast as possible for efficiency’s sake. It may sound counterintuitive, but when you’re trying to keep standups efficient and impactful, moments of pause are key. If an IC is considering voicing a concern, but hesitating, you want to create an opportunity for them to speak up — often those moments of hesitation give rise to the most important conversations.

Embrace fast follow ups – Block off 20 minutes of time after every standup for follow-up conversations. If something comes up during standup that requires further conversation, you’ll have a block of time to have that conversation with the relevant teammates while things are still fresh in your head. You won’t need to derail standup for a deep dive that doesn’t impact the rest of your team, but you won’t delay the conversation for too long either.

With these strategies, you’ll be on your way to running more effective, impactful standups. Your team will start the day of strong, poised to tackle their most challenging work and keep code moving through the development pipeline.

To find out more about using data to prepare for your standups, request a consultation.

Historically, engineering departments have been without reliable, objective metrics, leaving engineering leaders at a disadvantage in conversations with executives and board members. It’s part of the reason engineering is often viewed as a ‘black box’ — where departments like sales and marketing have clear numbers that demonstrate the efficacy of their processes, or their direct impact on the company’s bottom line, engineering has been reliant on reporting progress in ways that often raise more questions than they answer.

A list of features completed, for example, doesn’t convey the amount of work that went into delivering each feature, and doesn’t account for variations in difficulty or complexity. When a list is shorter one quarter, the immediate conclusion may not be that the features were more complicated, but that the engineering team is starting to fall behind.

Reporting on incidents is similarly flawed. The frequency of incidents may increase when the engineering team is encouraged to pursue an ambitious product roadmap without being afforded the time to address technical debt. These incidents may be seen as a reflection of subpar work by the engineering team, when in reality they’re a result of poor planning and prioritization.

To communicate effectively with the rest of the business, engineering needs to speak the language of the rest of the business. To do that, engineering leaders need objective metrics. Objective metrics translate across teams, individuals, and projects. They provide a concrete basis for critical conversations about everything from resource allocation to strategic decisions. Rather than simply asking stakeholders to trust your conclusions, you can use data to show them how you got there.

For example, you can make the case for increasing headcount by explaining that your current team isn’t large enough to keep up with the proposed product roadmap, or you can look at a throughput metric like Deploy Volume and illustrate the engineering team’s capacity with concrete numbers. On the flip side, you can demonstrate the success of a recent hiring push and illustrate the effectiveness of your onboarding practices with a graph of your team’s Cycle Time (a great proxy for engineering speed), demonstrating how quickly new hires are getting up to speed.

Trust is important, but it’s not enough. When you’re advocating for your department — pushing for key resources, raising an issue, or celebrating a success — data will help you make a stronger case.

Of course, metrics are not a replacement for experience, intuition, and expertise. As the expert, it’s still your job to put metrics in context, analyze them, and draw the right conclusions. When communicating with key stakeholders, you’ll need to choose the metrics that matter most to the rest of your organization, and situate them within the larger story of your department.

As you think about driving high performance on your team, it’s easy to focus on certain tangible improvements like optimizing processes, upskilling team members, and hiring new talent. But your team will only go so far if you neglect to cultivate a key aspect of team culture — psychological safety. Psychological safety, most commonly defined as the knowledge that you won’t be punished for making a mistake, is critical to the success of the highest performing organizations; it allows teams and individuals to have confidence in taking risks of all kinds, from the most basic risk of opening a Pull Request for feedback, to the larger leaps necessary to drive true innovation and stay ahead of the competition.

With the right data and a clear strategy for analysis, you’ll be able circumvent some common biases and assumptions, while fostering the psychological safety necessary to keep improving as a team.

Software Engineers Need Safety to Deploy

Safety is a prerequisite of speed; developers who aren’t confident in their code might become a bottleneck if they’re hesitant to open a PR and receive feedback. When your team has a culture of safety, that developer can feel more secure subjecting their work to the review process. They know they’ll have the opportunity to work through their mistakes, rather than being penalized for them.

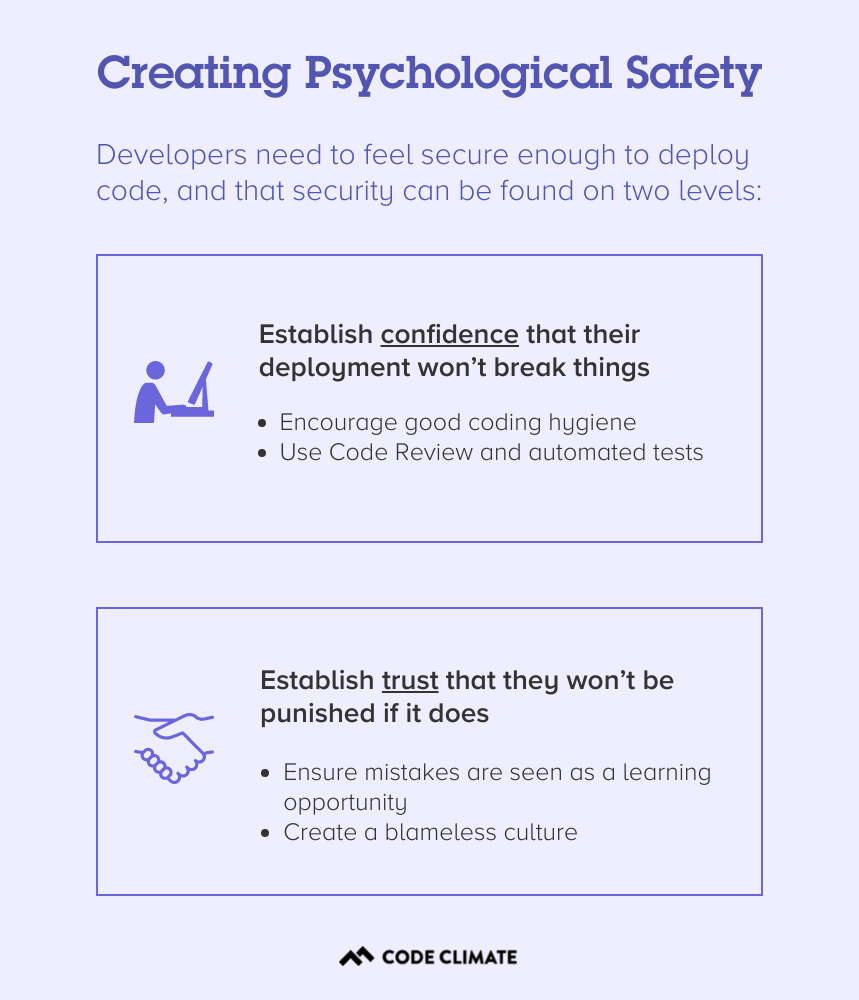

Psychological safety is also critical at the other end of your software development pipeline. Developers need to feel secure enough to deploy code, and that security can be found on two levels: the confidence that their deployment won’t break things, and the trust that they won’t be punished if it does.

The first is mainly a factor of process and tooling. Code Review and automated tests can offer some degree of confidence that buggy code won’t be deployed, while good coding hygiene, specifically the practice of keeping Pull Requests as small as possible, will mean that any damaging changes are easier to identify and reverse.

The second level, the trust that a developer won’t be punished if their code introduces a bug or causes an incident, is a matter of culture. It’s an engineering leader’s responsibility to create a culture of psychological safety on their team, and to ensure that mistakes are seen as a learning opportunity, rather than an occasion for punishment. In a blameless culture, the work is evaluated and discussed independently of the person who completed it, and every member of a team stands to benefit from the learning experience.

Without this foundation of trust, your team will be hard-pressed to deploy quickly and consistently, let alone take the larger risks necessary to pursue big ideas, innovate, and stay ahead of your competition.

Using Data to Create Psychological Safety

Data can play a key role in your efforts to cultivate a culture of psychological safety. Whenever you introduce data in your organization, it’s important to do so responsibly — be transparent, put all data in context, and avoid using it to penalize members of your team. But used properly, clear, objective metrics can help you combat intrinsic biases and check your assumptions, while keeping conversations grounded in fact. This makes it easier to keep conversations focused on the work, rather than the person behind that work.

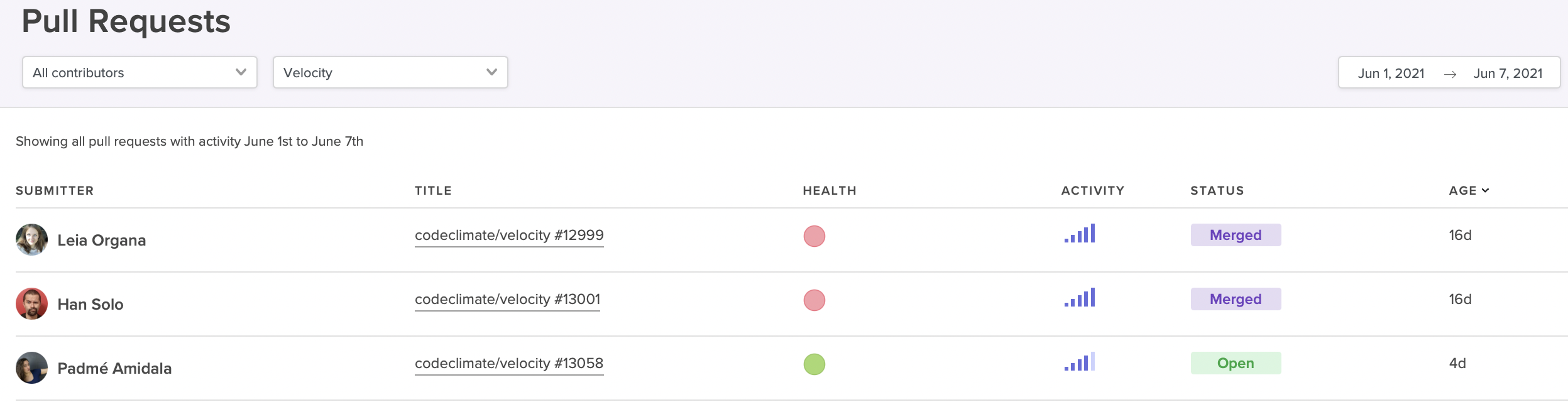

Surface high-activity Pull Requests that could be at risk of derailing your sprint.

For example, if a particular sprint is falling behind, you could frame the conversation in a general sense, asking the team why they’re moving slowly. But this framing risks putting your team members on the defensive — it could be construed as finding fault in your developers, and places blame on them for the slowdown.

With data from a Software Engineering Intelligence platform like Code Climate, it’s easier to ensure that discussions remain focused on the work itself. For instance, it’s possible to identify at-risk work before it derails your sprint. You can pull up a report that highlights long-running, high-activity Pull Requests, then dig into those PRs with your team. If you keep the conversation focused on those specific units of work, you’ll be better able to surface the particular challenges that are slowing things down and work through them together.

To find out how data can help you create psychological safety and drive performance in your organization, request a consultation.

Developers who are struggling to keep up, as well as those developers who are excelling but no longer growing, are likely to be unsatisfied in their current roles. But engineering leaders, especially managers of managers or those who are not involved in the day-to-day writing of code, may not have insight into who is in need of support and who is craving their next challenge.

With the right combination of quantitative and qualitative data, you’ll be able to spot opportunities to coach developers of all levels. You’ll also have an easier time setting and tracking progress towards concrete targets, which will empower your team members to reach their goals.

Start by Gathering Qualitative Engineering Data

Use your 1 on 1 time to initiate conversations with each of your team members about where they think their strengths and weaknesses lie, and what they’d like to improve. You may want to give your team members some time to prepare for these conversations, as it can be hard to make this sort of assessment on the spot.

Pay extra attention in standups and retros, keeping an eye out for any patterns that might be relevant, like a developer who frequently gets stuck on the same kind of problem or tends to surface similar issues — these could represent valuable coaching opportunities. It can also be helpful to look for alignment between individual goals and team objectives, as this will make it easier to narrow your focus and help drive progress on multiple levels.

Dig Into Quantitative Engineering Data

Next, you’ll want to take a closer look at quantitative data. A Software Engineering Intelligence platform like Code Climate can pull information from your existing engineering tools and turn them into actionable reports and visualizations, giving you greater insight into where your developers are excelling, and where they might be struggling. Use this information to confirm your team member’s assessment of their strengths and weaknesses, as well as your own observations.

You may find that an engineer who feels like they’re a a slow coder isn’t actually struggling to keep up with their workload because of their skill level, but because they’ve been pulled into too many meetings and aren’t getting as much coding time as other team members. In other cases, the quantitative data will surface new issues or confirm what you and your team member already know, underscoring the need to focus on a particular area for improvement.

A Code Climate customer and CTO finds this kind of quantitative data particularly helpful for ensuring new hires are onboarding effectively — and for spotting high-performers early on. As a new member of the team, a developer may not have an accurate idea of how well they’re getting up to speed, but data can provide an objective assessment of how quickly they’re progressing. James finds it helpful to compare the same metrics across new developers and seasoned team members, to find out where recent hires could use a bit of additional support. This type of comparison also makes it easier to spot new engineers who are progressing faster than expected, so that team leaders can make sure to offer them more challenging work and keep them engaged. Of course, as is true with all data, James cautions that these kinds of metrics-based comparisons must always be viewed in context — engineers working on different types of projects and in different parts of the codebase will naturally perform differently on certain metrics.

Set Concrete Engineering Goals

Once you’ve identified areas for improvement, you’ll want to set specific, achievable goals. Quantitative data is critical to setting those goals, as it provides the concrete measurements necessary to drive improvement. Work with each team member to evaluate the particular challenges they’re facing and come up with a plan of action for addressing them. Then, set realistic, yet ambitious goals that are tied to specific objective measurements.

This won’t always be easy — if a developer is struggling with confidence in their coding ability, for example, you won’t be able to apply a confidence metric, but you can find something else useful to measure. Try setting targets for PR Size or Time to Open, which will encourage that developer to open smaller Pull Requests more frequently, opening their work up to constructive feedback from the rest of the team. Ideally, they’ll be met with positive reinforcement and a confidence boost as their work moves through the development pipeline, but even if it does turn out their code isn’t up to par, smaller Pull Requests will result in smaller changes, and hopefully alleviate the overwhelming feeling that can come when a large Pull Request is met with multiple comments and edits in the review process.

Targets like these can be an important way to help developers reach their individual goals, but you can also use them to set team- or organization-wide goals and encourage progress on multiple fronts. Roger Deetz, VP of Engineering at Springbuk, used Code Climate to identify best practices and help coach developers across the organization to adopt them. With specific goals and concrete targets, the team was able to decrease their Cycle Time by 48% and boost Pull Request Throughput by 64%.

Though it’s certainly possible to coach developers and drive progress without objective data, it’s much harder. If you’re looking to promote high-performance on your team, look to incorporate data into your approach. You’ll be able to identify specific coaching opportunities, set concrete goals, and help every member of your team excel.

It’s important for a manager to know what their team members are working on, and to understand how that work is going. Still, how you get that information matters. Turning every standup into a status update or constantly checking in with engineers can be disruptive to developers’ flow, and can make your team members feel like you’re micromanaging their every move.

Status updates of this kind are also not productive for an individual contributor — you may need visibility into your team’s workflow, but looping you in isn’t providing value to your engineers. When your team stops what they’re doing to give you basic information, they’re not getting much out of the exchange.

If you get the visibility you need from data that already exists in your engineering workflow, you can dedicate your 1 on 1s, standups, and check-ins to higher-value interactions, whether that’s team-building, problem-solving, innovation, or professional development. Your team will be happier and more productive, and you’ll be able to use your meetings and conversations to make a bigger impact on your organization — and to empower your developers to do the same.

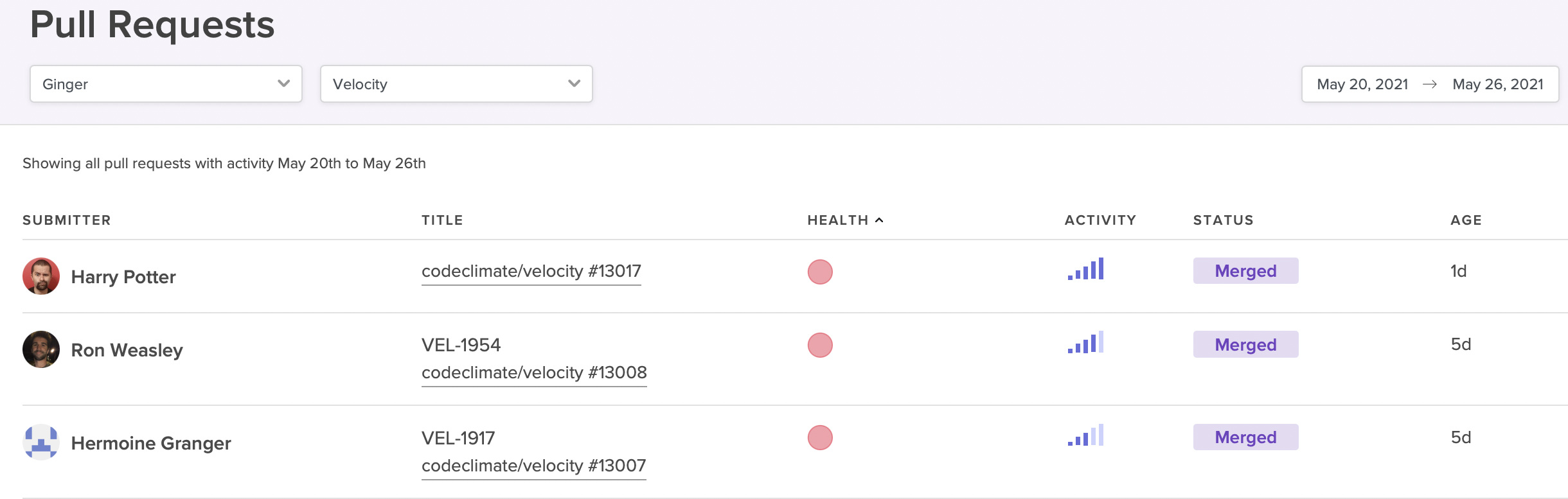

Get Visibility With Data, Not Check-Ins

Of course, you still need a sense of what everyone’s working on and how it’s going. Get that basic information from a Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI) solution like Code Climate, which gathers key information from your existing engineering workflow. You’ll be able to quickly get a sense of what each developer is working on and check that against your expectations of your team’s priorities and workload.

With that information, you can determine the best course of action for supporting your team.

When things are running smoothly, it’s likely best to take a step back and let your developers manage their own work. There may be opportunity for improvement — there always is — but that’s what retros are for. If you’re running effective retrospectives after each project or sprint, your team will still find opportunities to keep doing better.

Look For: A low PR Cycle Time, which indicates that Pull Requests are moving through your software development pipeline quickly and efficiently.

In the middle of a sprint, however, you’ll want to focus on work that isn’t going as planned, rather than work that meets your expectations. With Code Climate, for example, you can easily surface at-risk Pull Requests — PRs that are exceedingly large, have been open for long periods of time, or are taking up the attention of multiple members of your team. Some PRs are naturally larger and more complex, and that’s ok. But in some cases, these characteristics are red flags, signs that your team members could use your support. If you follow up on at-risk units of work, you’re likely to find opportunities to help your team members resolve bottlenecks or tackle challenges. You’ll enter meetings already informed, and you’ll be able to keep conversations focused and productive.

The Pull Requests report can help you easily surface at-risk PRs.

Look For: PRs that are exceedingly large, have been open for long periods of time, or are taking up the attention of multiple members of your team. (A Software Engineering Intelligence platform can help you easily surface at-risk PRs like these, based on information that already exists in your VCS or other engineering tools.) Some PRs are naturally larger and more complex, and that’s ok. In some cases, these characteristics are red flags. Talk to your team about any concerning PRs to determine whether your developers could use your support.

Use Data Responsibly to Avoid Becoming Big Brother

Even managers who barely think twice about interrupting an engineer’s workday to ask for an update worry that digging into data from their engineering workflow may feel invasive. The key to maintaining your team’s trust and fostering a greater sense of autonomy lies not in whether you have access to data, but how you use it. As a leader, it’s your responsibility to cultivate a culture of transparency and safety where metrics are used responsibly and constructively.

When Code Climate customer introduced engineering metrics at their organization, the CTO was careful to put them in perspective: “I spoke about Coe Climate and Cycle Time — how you measure a process, not people. And how you improve a process. I said to the team, ‘I’m going to start measuring the team just to measure the process and improve it. I’m not measuring individuals.’” With this groundwork, the team could surface key information about its workflow without constant check-ins and shoulder taps. As a result, they refined their processes and doubled their productivity, slashing their Cycle Time from 72 hours to 30 hours.

Visualize trends in the way your team is working.

When bringing data into your organization, it’s important to remember that:

- Data must be used with transparency. Your team members should know what information you’re looking at, who else has access to it, and how you plan to use it. Make sure you communicate openly and honestly about any plans you have to introduce data, and your goals for bringing data into your organization.

- Data should enhance, not replace conversations. Data doesn’t tell the whole story, and should always be viewed in context. Use it as a starting point for conversations, rather than using it as the basis for decisions.

- Data provides insights about the work, not the person. Engineering is collaborative, and it’s up to you to ensure no one feels personally responsible for issues or negative trends. Keep the focus on the work so your whole team can get behind improvement.

- Data should be used constructively, not punitively. Mistakes and shortfalls should be viewed as coaching opportunities, rather than occasions to take punitive action.

If you keep these principles in mind, you’ll be able to use data in a way that benefits you as a leader, as well as your team members as managers and ICs. Free of unnecessary check-ins and status updates, your team members will enjoy more autonomy and have more time to focus on their work. Together, you’ll be able to tackle larger challenges and make an even bigger impact on your organization.

Request a consultation to learn more.