Resources & Insights

Featured Article

Navigating the world of software engineering or developer productivity insights can feel like trying to solve a complex puzzle, especially for large-scale organizations. It's one of those areas where having a cohesive strategy can make all the difference between success and frustration. Over the years, as I’ve worked with enterprise-level organizations, I’ve seen countless instances where a lack of strategy caused initiatives to fail or fizzle out.

In my latest webinar, I breakdown the key components engineering leaders need to consider when building an insights strategy.

Why a Strategy Matters

At the heart of every successful software engineering team is a drive for three things:

- A culture of continuous improvement

- The ability to move from idea to impact quickly, frequently, and with confidence

- A software organization delivering meaningful value

These goals sound simple enough, but in reality, achieving them requires more than just wishing for better performance. It takes data, action, and, most importantly, a cultural shift. And here's the catch: those three things don't come together by accident.

In my experience, whenever a large-scale change fails, there's one common denominator: a lack of a cohesive strategy. Every time I’ve witnessed a failed attempt at implementing new technology or making a big shift, the missing piece was always that strategic foundation. Without a clear, aligned strategy, you're not just wasting resources—you’re creating frustration across the entire organization.

Sign up for a free, expert-led insights strategy workshop for your enterprise org.

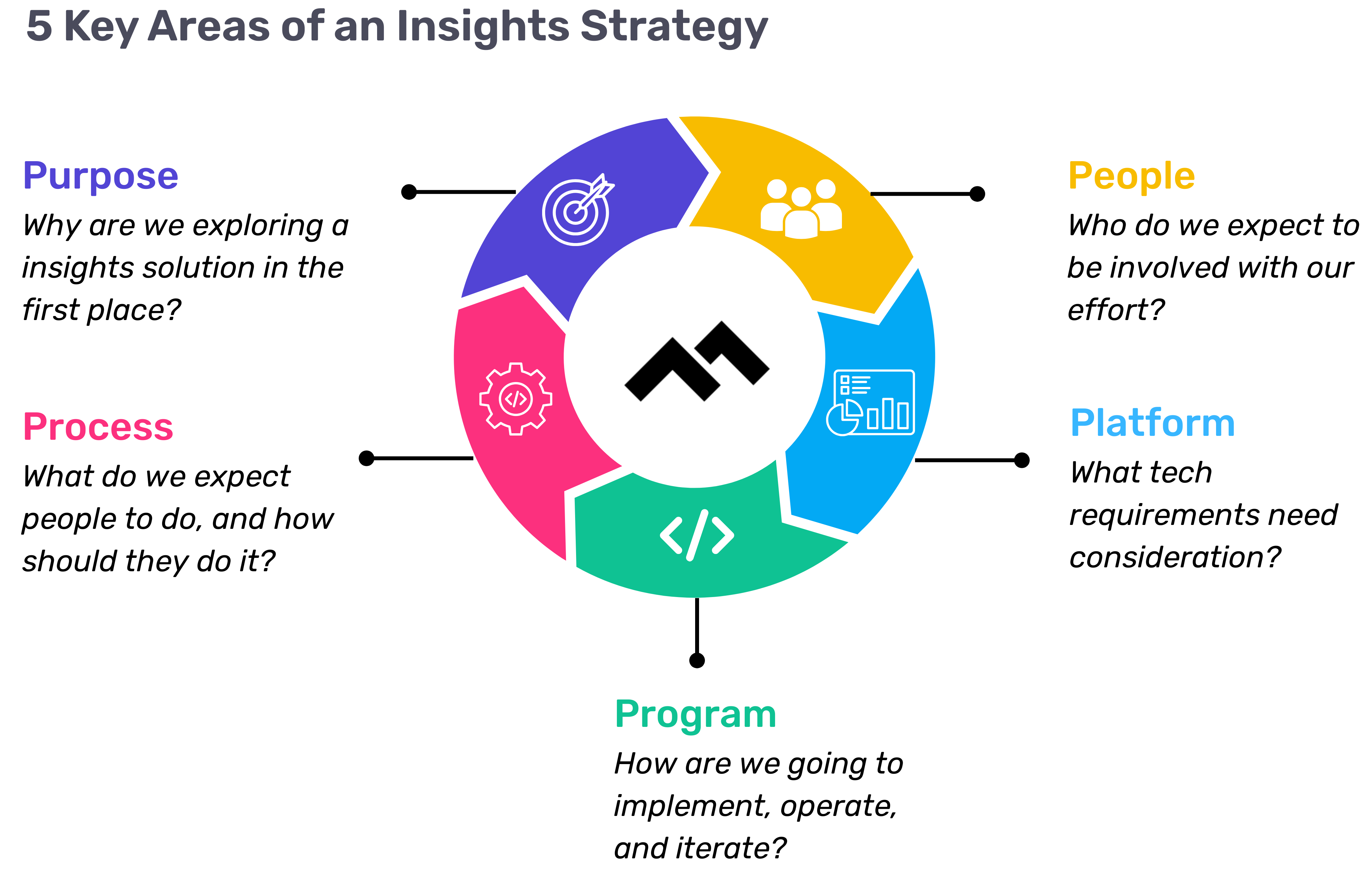

Step 1: Define Your Purpose

The first step in any successful engineering insights strategy is defining why you're doing this in the first place. If you're rolling out developer productivity metrics or an insights platform, you need to make sure there’s alignment on the purpose across the board.

Too often, organizations dive into this journey without answering the crucial question: Why do we need this data? If you ask five different leaders in your organization, are you going to get five answers, or will they all point to the same objective? If you can’t answer this clearly, you risk chasing a vague, unhelpful path.

One way I recommend approaching this is through the "Five Whys" technique. Ask why you're doing this, and then keep asking "why" until you get to the core of the problem. For example, if your initial answer is, “We need engineering metrics,” ask why. The next answer might be, “Because we're missing deliverables.” Keep going until you identify the true purpose behind the initiative. Understanding that purpose helps avoid unnecessary distractions and lets you focus on solving the real issue.

Step 2: Understand Your People

Once the purpose is clear, the next step is to think about who will be involved in this journey. You have to consider the following:

- Who will be using the developer productivity tool/insights platform?

- Are these hands-on developers or executives looking for high-level insights?

- Who else in the organization might need access to the data, like finance or operations teams?

It’s also crucial to account for organizational changes. Reorgs are common in the enterprise world, and as your organization evolves, so too must your insights platform. If the people responsible for the platform’s maintenance change, who will ensure the data remains relevant to the new structure? Too often, teams stop using insights platforms because the data no longer reflects the current state of the organization. You need to have the right people in place to ensure continuous alignment and relevance.

Step 3: Define Your Process

The next key component is process—a step that many organizations overlook. It's easy to say, "We have the data now," but then what happens? What do you expect people to do with the data once it’s available? And how do you track if those actions are leading to improvement?

A common mistake I see is organizations focusing on metrics without a clear action plan. Instead of just looking at a metric like PR cycle times, the goal should be to first identify the problem you're trying to solve. If the problem is poor code quality, then improving the review cycle times might help, but only because it’s part of a larger process of improving quality, not just for the sake of improving the metric.

It’s also essential to approach this with an experimentation mindset. For example, start by identifying an area for improvement, make a hypothesis about how to improve it, then test it and use engineering insights data to see if your hypothesis is correct. Starting with a metric and trying to manipulate it is a quick way to lose sight of your larger purpose.

Step 4: Program and Rollout Strategy

The next piece of the puzzle is your program and rollout strategy. It’s easy to roll out an engineering insights platform and expect people to just log in and start using it, but that’s not enough. You need to think about how you'll introduce this new tool to the various stakeholders across different teams and business units.

The key here is to design a value loop within a smaller team or department first. Get a team to go through the full cycle of seeing the insights, taking action, and then quantifying the impact of that action. Once you've done this on a smaller scale, you can share success stories and roll it out more broadly across the organization. It’s not about whether people are logging into the platform—it’s about whether they’re driving meaningful change based on the insights.

Step 5: Choose Your Platform Wisely

And finally, we come to the platform itself. It’s the shiny object that many organizations focus on first, but as I’ve said before, it’s the last piece of the puzzle, not the first. Engineering insights platforms like Code Climate are powerful tools, but they can’t solve the problem of a poorly defined strategy.

I’ve seen organizations spend months evaluating these platforms, only to realize they didn't even know what they needed. One company in the telecom industry realized that no available platform suited their needs, so they chose to build their own. The key takeaway here is that your platform should align with your strategy—not the other way around. You should understand your purpose, people, and process before you even begin evaluating platforms.

Looking Ahead

To build a successful engineering insights strategy, you need to go beyond just installing a tool. An insights platform can only work if it’s supported by a clear purpose, the right people, a well-defined process, and a program that rolls it out effectively. The combination of these elements will ensure that your insights platform isn’t just a dashboard—it becomes a powerful driver of change and improvement in your organization.

Remember, a successful software engineering insights strategy isn’t just about the tool. It’s about building a culture of data-driven decision-making, fostering continuous improvement, and aligning all your teams toward achieving business outcomes. When you get that right, the value of engineering insights becomes clear.

Want to build a tailored engineering insights strategy for your enterprise organization? Get expert recommendations at our free insights strategy workshop. Register here.

Andrew Gassen has guided Fortune 500 companies and large government agencies through complex digital transformations. He specializes in embedding data-driven, experiment-led approaches within enterprise environments, helping organizations build a culture of continuous improvement and thrive in a rapidly evolving world.

All Articles

As you prepare for your board meeting, you might be struggling to find some good news to share with the board. Sure, it’s a mistake to go into a board meeting pretending everything is going well — board meetings are a valuable opportunity to share your startup’s challenges and get guidance from a panel of trusted advisors.

But your current challenges don’t tell the whole story. It’s also important to highlight your company’s opportunities and to articulate your strategic vision for the coming months. To do that, you need to look beyond any suffering short-term KPIs. Revenue may be flagging, but other signs point to your company’s resilience and its ability to hold its own in a tough market.

To have an informed conversation about your company’s future, you need to communicate your company’s ability to add new value to your product, the speed at which you can ship that new value to users, your customers’ response to those new features.

You need to look at your company’s ability to innovate.

Innovation is a leading indicator. It’s not predictive, but it can hint at your company’s chances of future success. Software companies that are able to keep delivering new value to their users will be better positioned to retain their customers, outrun their competitors, and recover from a difficult year.

The shortfall of a feature laundry list

Of course, there’s no universal metric for innovation. At board meetings, engineering departments often share a list of completed features to communicate the value they delivered to users in the previous quarter. To signal the value to come in the upcoming quarter, many also share a list of features planned.

While important, a features list does not go far enough to capture the work the engineering department is doing. Features may require more work than anticipated, and priorities may change throughout the quarter. A company that decides to shift focus and enhance security protocols may not deliver on its planned feature list for that quarter. Still, those security upgrades represent innovation. They’re improvements that deliver real value to the customer, and they may even be critical to landing new deals or securing a foothold in a new segment of the market.

In her recent webinar, Code Climate’s VP of Engineering, Ale Paredes, shared her strategies for communicating with technical and non-technical stakeholders in the boardroom. Watch to find out how she uses engineering metrics to report on engineering’s challenges, progress, and opportunities.

Metrics that illustrate resilience

Complement the usual features list and any engineering KPIs you’re already sharing with metrics that highlight your company’s success in three key areas:

- Designing and implementing new value for your users

- Quickly shipping those new changes

- Turning your product into a must-have solution for your customers.

Feature Cycle Time

Feature Cycle Time speaks to your company’s ability to add new value to your product. It’s a measurement of the time it takes for a new feature to go from idea to implementation and can help you understand whether your team is working together effectively.

If the design process is efficient, product specs are clear, and product and engineering are aligned, it will be reflected in your Feature Cycle Time. A low Feature Cycle Time indicates that your team is frequently finding new ways to add value for your users.

Delivery Cycle Time

Delivery Cycle Time is a measure of how long it takes for code to go from a developer’s computer into deployment. It’s a way to isolate the execution portion of the development process and measure engineering speed independent of the variable feature design and planning process. Teams with consistently low Cycle Times are shipping code often, reliably and quickly delivering new value to users. This puts them in a strong position to outpace their competition.

Customer Retention Rate

A consistently high Customer Retention Rate demonstrates that your team is moving in the right direction and that their innovations are speaking directly to your customers’ needs and adding essential value to your product. If your Customer Retention Rate is high in a time when your customers are likely looking to make spending cuts, that’s a strong indicator that your product is a must-have for your users.

Keep moving forward

It’s been an unbelievably difficult year, and it’s likely that your short-term metrics reflect that. But with the right data, you can keep the conversation focused on productive ways to move forward.

In this time of global and economic uncertainty, it’s never been more important to have a quick way of knowing which engineering processes are working and which are broken.

And while it can be tempting to focus on bottlenecks and struggling team members, it can be even more useful to look at the practices, behaviors, and culture of your strongest teams.

This post runs through a framework for using Velocity, our Software Engineering Intelligence (SEI)platform, to identify and scale the most successful habits of high performing teams.

Finding the Top 5% of Your Organization

While all engineering organizations might define success slightly differently, there are two metrics within Velocity that indicate an extremely proficient engineering team:

- Throughput, measured in deploys or PRs merged, which indicates how much your developers are getting done.

- Cycle Time, measured in hours from first commit to when a PR is merged to production, which indicates how fast your developers are getting that work done.

In Velocity’s Compare report, you can select both of these metrics and compare them across your organization to identify the teams that are merging the most the fastest.

Once you’ve identified your strongest teams using success metrics like Throughput and Cycle Time, you’ll want to dig into what has made them successful. For this, you’ll need different, diagnostic metrics.

Identifying the Best Practices of Your Strongest Engineering Team

You can think of your software delivery process in three phases:

- Time to Open, or how long does development take.

- Review Speed, or how long does work sit before getting picked up for review.

- Time to Merge, or how long does the entire code review process take.

Typically, a strong engineering team will move faster in one of these stages.

Velocity makes it easy to look at these three metrics side-by-side. You can view them as bar graph clusters by week or by month.

Or, you can view these metrics by team.

Here, we can see that the top team — Gryffindor — is most distinguished by their extremely fast Review Speed. Although they have a long Time to Open and Time to Merge, this isn’t remarkable when looking at the other teams. The other teams (especially the Hogwarts team) frequently had work stuck in the review process.

Pair your quantitative analysis with qualitative information, and speak to the members of the Gryffindor team. Find out what makes their review process different from the other teams’ processes, and think about ways the other teams can apply those learnings.

DORA metrics are also useful to identify high performing teams within the organization.

Creating a Blueprint For Your Entire Organization

Now that you’ve identified your top-performing teams and their defining characteristics, you can create a blueprint for better processes across your organization.

One of our customers, a health data analytics solution,used Velocity following a Series B funding round to level-up the way they coached engineers at scale.

Their VP of Engineering had been brought on to help build out the engineering department. But after getting to know his teams, he realized that there wasn’t any consistency in how and when teams shipped features to end-customers.

The VP of Engineering worked with his engineering leads and product managers to identify agile practices that worked for his team, then shared them org-wide. Together, they created documentation and set up onboarding and mentoring around encouraging healthy coding habits at scale.

With stronger processes in place, the team was able to increase PR throughput 64%. With objective data and learnings from your highest performing teams, you’ll be able to replicate successful practices across your organization, and help boost productivity at scale.

Find out how Code Climate Velocity can help your team improve Cycle Time and PR Throughput by booking a demo.

For our series, 1:1 with Engineering Leaders, Code Climate and Codecademy for Business are speaking to managers and VPs about their career journey, leadership strategies, and advice for the next generation of engineers. Check out our previous interviews here.

Below is an excerpt from our conversation with Nitika Daga, Engineering Manager at Stitch Fix. Nitika spoke about helping developers learn from each other and being vulnerable as a leader. Edited for length and clarity.

For Nitika’s advice for early-career engineers, visit the Codecademy blog.

Tell us a bit about your current role and how you got to where you are now.

Nitika Daga, Engineering Manager, Stitch Fix: I am currently the Engineering Manager for one of the merchandising engineering teams at Stitch Fix. At Stitch Fix, half of our engineers work on stitchfix.com, what you as a consumer would see, and then the other half of us work on internal tools. So my team owns the merchandising platform that our buyers use to place orders and track inventory. I actually started on this team four years ago as a junior engineer, so I kind of grew on the team and then got an opportunity to become a manager of the team, which is great because I have a lot of domain knowledge that helps me in my current role. Prior to this, I was an engineer at another retail tech company. That’s really what I’m excited about and passionate about and what I’ve spent my career in. And then prior to that was my first job out of school. I studied Computer Science at Berkeley.

Can you tell us a bit about your transition from IC to manager?

I got really lucky. I had expressed that at some point in the future I was interested in management. My ultimate career goals are to be a CTO one day, and obviously moving into management at some point is a prerequisite for that. And then my manager at the time left for his parental leave, which is four months at Stitch Fix, and we needed someone to step in during that time. So I got to kind of try it on, in a less pressured way. Usually you go into management and it’s hard to go back, but I got four months to see if it was something I wanted to do, and then after those four months I decided I liked it. My manager decided to become the manager of another team, so I got to move into that role full time.

What was it like starting to manage a team that you had previously been a part of?

It was interesting. Some things were really good. I had the domain knowledge. I knew the technology we were talking about. I could speak to it from experience, and then when doing things like estimates, I could say, “Yeah, that feels right,” versus, “I’ve never been in this codebase so I have no idea.” Some of the challenges were obviously going from being peers with folks to moving into managing those folks, and there’s some tension that can actually arise.

I’m really lucky that I have a great team and they never made me feel like, “Oh, this is weird. You used to be our peer.” They put their trust in me, which I really appreciate, because that could have been a big cause for imposter syndrome or just like, “Hey, I don’t actually think I’m cut out for this.” They never made me feel that way.

What interested you in becoming a manager? I know you said your aspiration ultimately is to be a CTO — why are you interested in that trajectory?

I think a few things. One, I think I’m just interested in the impact that can have. You hear stories about how a good manager can make or break someone’s career, both at a company and then in tech as a whole. A lot of people just leave tech if they have bad managers. The second thing is I have found it really powerful in my career when I have a manager or someone in leadership who I can relate to and who looks like me. Stitch Fix has a female CTO, I have a fully female reporting chain, and I think it’s a little bit of like — you can’t want to be what you can’t see. Being that person for someone really inspires me to be an engineering manager who doesn’t look like a lot of engineering managers.

What do you see as the role of a manager on an engineering team?

I guess I see my role as two-fold. One is translating what the business needs at a high level into problems my engineers can solve and then clearing the way and enabling them to do what they do best and go out and solve those problems. My engineering team has way more technical knowledge than I do. So my job is to give them the problem and put it into a scope that they can understand and then let them run with it. I clear the way for them, give them the resources, make sure they’re talking to the right people, and they can go out and solve that problem for the business. The second part of my role is advocating for my engineers, whether it’s tactically for a promotion or an opportunity to work on an exciting project, or whether it’s advocating for the technical approach they have proposed and making sure all the other teams are bought onto it. Just advocating for them upwards and outwards.

Got it. Is there a difference between being a manager and a leader and if so, what’s the difference?

I think there’s a difference between being a people manager and a technical leader, and I think teams need both. This is something I learned the hard way — if I know the technical details of everything my team is working on, I’m probably not focused on the right things. That is not my job anymore, and so I need a technical IC leader, like a Principal Engineer who can be focused on the technical details and lead in a technical sense, where I kind of look at the future of what we’re building in more of the people management aspect of it. So I think they’re different but complementary.

What are the biggest challenges you faced since moving into a management role?

That’s a good question. So I transitioned into manager in January, so two months before COVID hit. So I’d say the whole time has been a challenge. Luckily one of Stitch Fix’s core values is, “Motivated by Challenge.” So it’s very much in the ethos of our company.

The biggest challenge for me is has been balancing compassion for my engineers as they figure out what their new normal looks like with homeschooling or sharing a space with their partner or having to move, versus being accountable to the business for deadlines. I’m balancing those two things and making sure my engineers don’t burn out while we’re still delivering value to the company. My first priority is making sure my team is happy and healthy and can take care of themselves and their families, but also we’re a business and I need to deliver things in order for all of us to keep having jobs.

Yeah. I’m sure it’s really, really tough. You’re talking about making sure developers are happy and healthy — how do you help them grow, both as individuals and then together as a team?

This is my favorite part of the job. Promoting people and helping people grow and achieve things they didn’t think they could do is so much fun. There are a few things I do. One is, I try to understand their aspirations. Something that’s really been clear in the last nine months is some people are just happy where they are. They’re not seeking that next promotion because there is enough going on in the world. So it’s about really coming to a common understanding, and giving them growth opportunities that are maybe still in their comfort zone and don’t stretch them too much. And then taking those engineers who do want to grow, and just giving them the right opportunities. Again, the technical knowledge of my team is stronger than mine, so it’s really matching them to the right opportunity and then letting them run with it within the right guardrails.

And then in terms of growing as a team, again I think it’s pairing the right people together. We do a lot of pair programming at Stitch Fix, especially now that we’re remote. So looking at the skills that I know a Senior Engineer has, and pairing them with the right Junior Engineer so that Junior Engineer can run and grow, and team members can lean on each other to grow their skill sets.

As a remote leader, how do you make sure you’re able to really understand what your team needs?

Stitch Fix engineering was 50% remote prior to this. I was living in New York earlier this year and I just recently moved back to the Bay, but only one person on my team is in HQ. Having more recurring one-on-ones and touch bases, and really leaning into async communication because we are spread across time zones. And then specifically for understanding how is the team working together and what do we need, we do retrospectives every sprint. I also really drive home the point that feedback is a gift for managers. We don’t get it that often, unless things have gone really terribly wrong. You can’t fix something if you don’t know it’s not working, and so I really work on building that trust with my team so they feel like they can give me that feedback, and then trying to get that feedback from different avenues so we can try new things and figure out what works for the team as the environment changes around us.

What advice do you have for new managers or for people who are looking to make the shift into a manager role?

I think one piece of advice I got from my current manager that I found really powerful was to lean into the vulnerability of being new at something. If you’re managing a team, it’s easy to pretend like you have all the answers, you have everything figured out. But I’ve been doing this for 9 or 10 months now and I’m still figuring out my management style and what works for me. Be upfront about that, let your team know, “Hey, I’m going try a few things out. Let me know if they’re not working until I figure out what’s working.” It lets your team know that you’re trying things out and that you don’t have all the answers. Being vulnerable as a leader gives your team permission to be vulnerable back to you, and that just builds more trust and you get better and more honest feedback that way.

So don’t pretend like you have all the answers. Do that figuring out in front of the team because it’ll make them trust you more, not less.

For more of Nitika’s advice for the next generation, visit the Codecademy blog.

Your engineering speed is your organization’s competitive advantage. A fast Cycle Time will help you out-innovate your competitors while keeping your team nimble and motivated. It’ll help you keep feedback loops short and achieve the agility necessary to respond to issues quickly. Most importantly, it’ll align everyone – from the CTO to the individual engineer – around what success means.

To discuss Cycle Time and its implications, we invited a panel of engineering leaders and industry experts for a virtual round table.

Code Climate Founder and Former CEO, Bryan Helmkamp, was joined by:

- Bala Pitchandi, VP of Engineering at VTS

- Katie Womersley, VP of Engineering at Buffer

- Bonnie Aumann, Remote Agile Coach at CircleCI

Over the course of the hour, these panelists covered topics such as using metrics to design processes that work for your team, building trust around metrics, and tying delivery speed to business success.

Here are some of the key takeaways:

Prioritize innovation over semantics.

Bryan Helmkamp: When I think about Cycle Time, I think about the time period during which code is in-flight. And so I would start counting that from the point that the code is initially written, so ideally, the time that that code is being typed into an editor and saved on a developer’s laptop or committed initially, shortly thereafter. Then I would measure that through to the point where the code has reached our production server then deployed to production.

Bala Pitchandi: I define Cycle Time as when the first line of code is written for a feature — or chore, or ticket, or whatever that may be — to when it gets merged.

Bryan Helmkamp: I think it’s also important to point out that we shouldn’t let the metrics become the goal in and of themselves. We’re talking about Cycle Time but really, what we’re talking about is probably more accurately described as innovation. And you can have cases where you’ll have a lower Cycle Time, but you’ll have less innovation. It can be a useful shorthand to talk about (e.g., we’re going to improve this metric), but really that comes from an objective that is not the metric. It comes from some shared goal. That understanding matters much more than the exact specific definition of Cycle Time that you use because really you’re going to be using it to understand directionality: are things getting better? Are they things getting faster or slower? Where are the opportunities to improve? And for that purpose, it doesn’t really matter all that much whether it’s from the first commit or the last commit or whether the deploy is included; you can get a lot of the value regardless of how you define the sort of thing.

The faster you fail, the faster you innovate.

Bala Pitchandi: When I was pitching this to our executive team and our leadership team, I used the analogy of Amazon and Walmart. Most people think that Amazon and Walmart are competing against each other on their prices. But keeping aside the technology parts of Amazon, they’re basically retailers. They both sell the same kind of goods, more or less, but in reality, they’re competing against each other on their supply chain. In other words, you could sell the same goods, but if you have a better supply chain, you can out-execute and be a better business than the other company, which may be doing the exact same thing as you are. And I think that I was able to translate that to the software world by pointing out that we could be building the same exact software as another company, but if we have a better software delivery vehicle or software delivery engine, that will result in better business goals, business revenue, and business outcomes. That resonated well, and that way, I was able to get buy-in from the leadership team.

Katie Womersley: The most interesting business discovery we’ve had from using Cycle Time has been where it’s been slow. It’s been a misunderstanding on the team about what is agile, where we’ve thought, “Oh, we’re very agile.” Because we’ve had situations where we’re actually changing what we’re trying to ship in PRs — we’re reworking lines of code because we think that we’re evolving by collaborating between product managers and engineers with the PM changing their mind every day about what exactly the feature is. And the engineer says, “I’ll start again, I’ll start again, I’ll start again.” And the team in question felt this was just highly collaborative and extremely agile, so that was fascinating because, of course, that’s just not effective at all. You’re supposed to actually get something into production and then learn from it, not just iterate on your PRs in progress. We actually need some clarity before we start coding, and I do believe that that had business impact on knowing what we were shipping.

Bala Pitchandi: We believe in this concept of failing fast. We want to be able to have a small enough Cycle Time to ship customers something quickly. Maybe it’s a bet on the product side, and wanting to ship it fast, sooner and get it into the customer’s hands, our beta users hands, and then see if it actually sticks and if we’ve been able to find the product market fit. That failing fast is really valuable, especially if you are in the early stage of a product. You really want to get quick iteration and get early feedback and then come back and refine your product thinking and product ideas.

Embrace resistance as a learning opportunity.

Katie Womersley: I got quite a bit of pushback on wanting to decrease Cycle Time. Engineers were really enjoying having work-in-progress PRs. They liked being able to say: well, here’s the shape of something, and how it could look as a technical exploration, and some of that was actually valid… But the real concern here is, we are using metrics as a way to have data-informed discussions. It’s a jumping-off point for discussion. It is not a performance tracking tool. And that seems to be the number one thing, and that’s important. We’re not trying to stack rank who has the most productive impact and then fire the bottom 30%. We’re trying to understand at a systems level where there are blockages in our pipes; we’re trying to look at engineering as a system and see how well it’s working. I think that’s very, very important to communicate. I think for software engineering in general, we have a great culture for the most part of blameless postmortems, understanding human factors in engineering, and not attributing outages solely to human error. Basically, you want to take that mindset that you already have from incident response and incident management, and you want to apply that now into team process management as well.

Bonnie Aumann: Esther Derby has a podcast called Tea And The Law Of Raspberry Jam, which actually has an entire episode on coaching past resistance, and the most important part is actually to try to take that word out of your vocabulary. Resistance almost always comes from somebody who really cares and sees value in what is happening. And if you can understand where they’re coming from, you can learn better about how you might introduce something and get a better idea of what will benefit the team and the company. And it’s not to say that you need to be held hostage by one cranky person, but that one cranky person might just have liked a little bit more information for you than you knew before.

Bryan Helmkamp: In speaking with so many engineering organizations and getting started with data and insights, I think it can feel a little bit difficult to get started. It can feel a little bit like, “We have to get this exactly right.” And it’s common that people, as with anything, will make some mistakes along the way. So my recommendations for that are, give yourself the space to start small, maybe just looking at even one tactical thing. “How long is it taking for us to get code reviews turned around?” is a great example. Really focus on building up trust through the organization because trust is a muscle. And as you exercise it, it’s going to grow. Incrementally paint the picture to the team of what you’re trying to achieve and give them the why behind it, not just the what.

Design a Code Review process that works for your team.

Katie Womersley: Something that we do – and this is really controversial – but the vast amount of PRs are merged without review. This will probably shock many people, and the reason we do that is in every asynchronous team: when you’re waiting for review, you lose context…We have a rating system for our PRs. In fact, most of them are small PRs. They’re uncontroversial changes. And we actually don’t need that developer to wait a whole day for somebody to come online to say: ‘Arms up, let’s march.’ It’s just not that risky. Also, we’re in social media management. We don’t make pacemakers. Just from a business perspective: how badly wrong can things go? Most of our PRs are absolutely safe to merge without review. And then you will get PR comments, which are aimed at individual growth and performance, saying this could have been done in a cleaner way, for example. And then on the next PR, hopefully, the engineer would incorporate that advice.

For high profile PRs (e.g., you’re changing Login, you’re changing Billing), yes, that needs to get reviewed before going out … Most people will say it’s really important to have code reviewed before you merge things. And is that nice to do? Yes, it is. But in our very asynchronous team, what is the effect of doing that? Actually, it is a negative effect. So a lot of our code does not get reviewed before merge.

Bala Pitchandi: I couldn’t agree more on the over-relying on reviews. At VTS, we do pair programming a lot. Even when two developers were paired on a PR, we used to still require a third person to review. Later, we just figured that two people working on a PR is enough of a review, so that if you’re pairing on a PR, you just merge it.

As coding days go down, productive impact scores go up.

Bala Pitchandi: I guess, of all the bad things that happened with the global pandemic, one benefit was that we all went distributed. Our Cycle Time actually went down by 20% without having to do anything. Something that you often hear about engineers is that they’re always complaining about distraction. There’s too much noise, people are talking, they want a noise-canceling headset. We were like, you know what? There is actually truth to that because when everyone went remote, guess what? There was less distraction, they had more heads-down time, and they were actually able to contribute to getting the code through the pipeline lot faster. And then we were able to build on that. Focusing on the team-level metrics and encouraging the teams to really focus on their own things that they care about was really helpful.

Bonnie Aumann: We’ve been remote from the beginning. The pandemic made everything more intense. I think is what we really learned. And the thing that became harder was making sure that people took the time and space to actually turn off and recharge. One of the anti-pattern practices is that on a team of very senior people, each person will take something to do and then push it forward. But then, of course, your overall Cycle Time on each of those goes down because you haven’t focused on pushing it all the way through. I think there’s been a lot of cultural outreach from managers to employees to be like, have you hydrated today? Have you done your basic care? When was the last time you saw the sky? It makes it more of a complete package.

Katie Womersley: I have a great mini-anecdote on that. We switched to a four-day workweek to get ahead of burnout with the pandemic. And what we saw in our data was, while the number of coding days went down; obviously, it’s a four-day workweek. We actually saw a productive impact score go up across every single team…We’re getting more done in four days than we were in five days, which is completely wild, but we can show that’s working. We’re in company planning discussions now, and we’re asking, “Should we move back to a five-day workweek to get our goals achieved?” But the data actually shows that we’ll get less done because people will be more burned out.

Agile provides teams with valuable vernacular, but be wary of doing agile by the book.

Bonnie Aumann: I think it’s complicated, but I’ll try and narrow it down. An absolute unit of agile is feedback and feedback cycles. When you’re looking at a thing like Cycle Time, it is a tool to let you know how fast you’re going, but it’s just information. What you do with that information is up to you. If you see people are working seven days a week and you think that’s a good thing, then you’re going to use it to make sure that it’s a good thing.

I will say that one of the things that is beneficial of doing agile by the book, particularly if you’re doing it by The Art of Agile Development or some of the books that really get down into the nitty-gritty, is that you have everybody speaking the same language, you have people using the same words. Because one of the hardest things about getting good metrics on a multi-team situation is making sure that people are using words the same way. And when something opens and when something closes, is when something starts and when something finishes. If you’re using Trello in one place and JIRA in another place, and GitHub issues in a third place, getting that overall view of what your data is, is challenging.

The more you rely on concrete data, the more flexible you can be.

Katie Womersley: It’s so important to look at your metrics and figure out what actually works with the team you have and the situation you’re in, and not just listen to a bunch of people on a panel and be like, “We must do that.”

Bryan Helmkamp: Your point reminded me of an interesting quote about agile and just this idea of process adherence becoming the goal in and of itself. I think the quote was something like, if you’re doing agile exactly like the book, you’re not actually doing agile. It’s inherent. To bring this around to Cycle Time and data, the answers are different for every team. But what I think is really powerful is that by having a more clear objective understanding of what’s going on, that opens the door to more experimentation. And so it can free up a team to maybe try a different process than the rest of the org for a while. Without it just being like: Well, we feel this or that, and being able to combine both of those things into a data-informed discussion afterward about how it went and being able to be more flexible despite the fact that data may make everything feel more concrete.

For our series, 1:1 with Engineering Leaders, Code Climate and Codecademy for Business are speaking to managers and VPs about their career journey, leadership strategies, and advice for the next generation of engineers. Check out our previous interviews here.

Below is an excerpt from our conversation with Smruti Patel, Engineering Manager at Stripe. Smruti spoke about getting to know your team members, the importance of delegation, and the power of well-designed metrics. Edited for length and clarity.

For Smruti’s advice for early-career engineers, visit the Codecademy blog.

Tell us about your current role, and your career journey up to this point.

I currently lead the LEAP organization — that stands for Latency, Efficiency, Access & Attribution, & Performance — and Big Data platform engineering at Stripe. I came to Stripe after 11 years at VMware, where I worked on their enterprise disaster recovery solution and data protection for the cloud. So, looking back at my career, I’d say I’m a generalist at heart who loves bringing a rich, diverse set of people together to solve complex, ambiguous problems. And I’ve been leading teams and organizations for almost a decade.

Did you start out as an IC?

Yes, I started off as an engineer back at VMware after a Master’s in Computer Science. I moved from New York to California when I saw nice skies and better weather. I started off at VMware as an automation engineer. And then I moved to managing the team that I was working with. From there, I transitioned to managing and leading multiple teams.

What was the transition like from being an IC to managing one team? And then the transition to managing multiple teams?

VMware was very thoughtful, and still is, in developing its engineers and growing its engineers. There are dual tracks, where you can grow as an individual contributor, or you can pivot to the management track.

I was deciding whether I wanted to move to Staff Engineering or to be a manager. At that point, my manager approached me to manage the team I was on, and I was already owning a lot of the day-to-day tasks around technical design decisions, communicating to different stakeholders, figuring out release timelines, mentoring junior engineers, and in general defining the strategy for the team.

So it seemed like a logical next step, although looking back, I decided to switch to management in big part because I thought I’d have higher authority and autonomy in driving the product strategy. So I would say I probably got into it for the wrong reasons, because I soon realized I couldn’t do a lot of that.

But I stayed for the right reasons. I like seeing people grow, giving them feedback, identifying what made each engineer tick, and seeing an excited, motivated set of people come together to work magic to solve complex business needs.

And then another big switch came to me when a peer manager approached me to see if I wanted to manage one of the development teams alongside the automation team. And that was a second switch.

One thing I’ve learned, looking back, is always say, “yes.” Raise your hand when an opportunity comes knocking. I think the switch there was from managing engineers to managing engineers and managers or multiple managers. The shape of the challenge there is slightly different.

Got it, and how is it different?

One thing that is common to both is that you’re trying to walk that line of either being a mentor or a coach or a sponsor, and asking open-ended questions. The thing that I found different is that now there’s this level of indirection, so to speak.

Identifying how the team is doing, debugging team engagement or velocity required me to delegate a lot more. While managing managers, you have to let them drive some of the strategy and the vision for their team. So the scope of what you delegate changes.

What do you see as the role of a manager and the role of a leader? Are they different, or are they the same?

I think about that a lot, because walking that line and being one or the other at the right time is important. I’ll start with being a manager. Three to four things come to mind here. One is hiring the right set of people. The team composition based on diversity in skill set, in representation, in perspectives in experiences, is super crucial. That I think is almost the number one priority of the manager.

Now that you’ve got folks, and you’ve got them in the door, how do you then set them up for success? So the second thing that I think managers should focus on, which I personally do a lot of, is ongoing 1 on 1s. How do you set up expectations around what the business needs are? How do you determine what level each engineer is at? How do you support them through challenges, whether they are technical, or organizational, or even personal sometimes? You’re doing that by building trust through vulnerability both ways, and ongoing feedback. Radical Candor is a really good book on frameworks for providing that ongoing feedback, whether it is constructive or critical. Quite often managers focus on things that could be better, but it’s equally important to be able to reinforce the positive, and to say, “continue doing this,” or, “you’re doing great on this.”

So, once you set them up for success, the other thing I especially try to do is to provide access to opportunities to all. Having been — well, I still am — a brown woman leader in tech, I’ve had my fair share of not having access. So something I’m extra mindful about is ensuring access to opportunities, to those big risk, big reward situations, for every person on my team. I go ahead and identify those stretch opportunities that are uniquely catered to their strengths, or their interests, or their career aspirations.

And so that’s on the hiring and the team building side. The other big area that managers focus on is engineering. There’s the planning: Why are we building? What are we building? And there’s the execution, which is: How are we going about building? How are we measuring it? This is where engineering velocity comes into picture. Third, there’s delivery, which is: Is it really done? And making sure your feedback loops are actually telling you the story you wanted to tell, and that users are happy. And as you’re building all these new, shiny things, they have to last the test of time or the orders and magnitude of scale.

So, building teams, setting them up for success, and ensuring that we are doing what we are actually here to do. And then you have to bridge the gap. I think quite often I see a gap between what the team is doing and what leadership expects the team to do. So it’s important to bridge the gap between the business and the individual by being the advocate for the team, the team’s impact, and the engineers’ contribution. That can involve getting stakeholder buy-in, resolving conflicts, addressing concerns, and sometimes even marketing the team’s work.

That’s management. The way I think about it is, if you were to draw a Venn Diagram, all leaders are not managers, and all managers are not leaders.

Leaders are the ones who drive changes organizationally. They are able to influence others, not through authority, power, or control, but by motivating the right set of goals, elevating the collective ambitions, and then demonstrating success. And that’s the subtle difference that I see between managers and leaders. Where managers have to be focused on a lot of the tactical side of things, I’ve seen leaders bring along the strategic and the visionary elements. And that means ICs can be leaders too.

How do you drive high performance on your team, both at the individual level, and at the team level?

This one really keeps me up at night. It goes a lot to not having a cookie cutter approach in general. That’s why I focus a lot on regular 1 on 1s with every person on the team, because that’s where I develop a better understanding of what motivates each person, what challenges each, what drives each. Everyone is at different stages, in their careers and in their lives, and a pandemic doesn’t help. Each situation is very different at home. So it’s important to be able to connect with everyone and understand what their unique strengths are and what are they looking to grow into, and to take a longterm career view.

I tell a lot of my reports that once I manage you, I manage you for life. Because it’s not about whether you are on a team that reports into me. It’s about where you see your career, and how I can best support you for the longer term. I try to marry the team’s deliverables with their individual aspirations. And I try to do it in a very transparent and consistent way, and to make sure that all the voices in the room are being heard, and that the access to opportunities is going across the team.

It’s important for everyone to have the opportunity to be the DRI, or Directly Responsible Individual. You lead a project from design through execution, leading other engineers, both within the team and across. So, being a DRI is sort of a big deal. I make sure that the same set of folks are not always raising their hands. And that’s why I run a very transparent, consistent DRI selection processes while highlighting what is required. And I’ll sort of nudge people and say, “Hey, you would be good at this, why don’t you apply?”

And then what is more important is making sure that folks have the psychological safety to fail. High growth comes for individuals when they take on big, risky things. So I try to make sure that all people on the team are taking those risks as well, and I give them the safe space with good feedback and space to fail. If they succeed, that’s awesome, they’ve stretched themselves and in the process, they learn.

The meta thing in all this that I communicate with the team, is the growth mindset, which ensures that everyone’s learning and growing as we go, because that’s what the organization needs.

Now that we’ve talked a bit about performance — how do you approach engineering velocity on your team?

I manage six teams right now, and each team is in a different state team maturity, so the shape of all six teams is very different. At the planning stage, I work on getting alignment, and then prioritizing and focusing on the right things.

In execution, you drive speed and quality, how you’re doing things. This is where Dr. Nicole Forsgren’s Accelerate book is really awesome. It helps you identify whether you are tracking the right metrics and evaluating whether the team’s execution is where it needs to be.

I tie it back to: here was the metric we signed up to solve for, here’s the problem we were looking to solve, and here’s how the needle has or has not moved. Tying that feedback loop together becomes super crucial during delivery.

You also have to pay attention to operations and maintenance, and make sure that the less glamorous bits are not sucking up all your soul, because you do want to keep doing the strategic innovative work. At the same time, if 80 to 85% of your team is bogged down, just keeping the lights on for the stuff that you’ve shipped, then you’re not going to be able to invest in new things.

We frequently hear that managers worry their team members will be resistant to using metrics. How did you approach that? How do you get your team members comfortable using them?

This happens so often that it makes me smile. I personally view metrics as something that has to be used carefully. They can do a lot of harm, and the right metrics, when crafted correctly, can also do a lot of good.

A well-defined metric can drive alignment with stakeholders and leadership. It can help drive prioritization and focus within the team. But it can also help the team say, “Hey, here’s a metric we really care about, which the company cares about, and clearly we’re under invested. Here are the projects we need to do to move the needle.” When done right, they can really increase the overall impact the team can have.

But there can also be times when the team may not feel like it’s in full control of its own priorities, or when it could be over-indexed on some wrong metrics. That can have them start losing faith in the system.

One of our teams was measuring their overall efficiency in terms of how our standard infrastructure is increasing as a function of Stripe’s business. This is a very company-level metric, because it’s not that my team actually spends the money on all the infrastructure. It’s about the money that everybody at Stripe engineering spends. So, a natural question the team had is, “How are we accountable? And why are we accountable for the top-line spend when we do not have the agency control a lot of it?”

That was a very interesting thing. It was very true, we couldn’t move the overall needle. But we’re Efficiency, we’re sort of the last line of defense. So how do we then push the envelope and bring about organizational change, so we can see areas with pockets of inefficiencies? The only way to do that is to have a true North Star, company-wide metric, which we drive, which we provide visibility on.

So these engineers saw leadership acknowledge that this needle moving up and down is not solely Efficiency’s responsibility, but that Efficiency is an enabler to that change, and will be the voice of reason. Leadership communicated that if it’s down, you’re obviously responsible for it being where it is. But if it were to go up, hearing from you on the causes and the drivers is what we would hold you accountable for.

I’m going to transition a little bit more into general advice. But before I do that, is there anything else around metrics that you feel is important to say?

Metric design sounds obvious, but it can be very challenging at times to measure the right stuff. It’s hard to walk that line in designing the right metrics, which the team can own, and which really move the needle on impact. Word of caution, but you know, with great power comes great responsibility.

What advice do you have for new managers, or for people looking to shift out of an IC role and become a manager?

At least in well-designed engineering systems, management isn’t the only way to up-level yourself. I personally would suggest running away from such systems if you have the privilege to do so. Truly well-designed systems have an IC track, and a management track.

And then, avoid the new manager death spiral, which happens when you want to own and control it all. When you’re in IC, you’re in full control of your destiny, you know what your project is, you know how to scope it, how to design it, how to execute. But as a manager, I think the first thing you need to do is give some of that control away. It’s worse if you actually go ahead and do everything, because you’re not letting your team take on some of that.

You also have to get comfortable in the unknown, because you’re not coding day to day. And if you are, then you’re you’re not doing what you are uniquely positioned to do and accountable to do, which is be there for the team, be there for individuals on the team and grow them and motivate them. You need to delegate, and to share your trust and faith that your team will grow into it.

Don’t see management as a promotion, see it as a shift in role, and acknowledge that it will be a bit uncomfortable for you, and give yourself space to be okay with that. The output of the manager is not very tangible in the near term. It’s a lagging indicator of success, and the feedback loop is longer. So, it takes time for you to see how you are being effective.

Remember, you don’t have to have all the answers. And you don’t have to always be right either. You need to be open, be curious, and at times be vulnerable. The job is to find and hire the most brilliant minds with a complementary and diverse skill set, and get them together. And your unique responsibility is to create the environment for that set of folks to flourish as they work together.

For more of Smruti’s advice for the next generation, visit the Codecademy blog.

For our series, 1:1 with Engineering Leaders, Code Climate and Codecademy for Business are speaking to managers and VPs about their career journey, leadership strategies, and advice for the next generation of engineers. Check out our previous interviews with Tara Ellis, Manager, UI Engineering at Netflix, Brooks Swinnerton, Senior Engineering Manager at GitHub, Gergely Nemeth, Group Engineering Manager at Intuit, Lena Reinhard, VP of Product Engineering at CircleCI, Mathias Meyer, Engineering Leadership Coach, and Anchal Dube, Senior Engineering Manager at Zocdoc.

Below is an excerpt from our conversation with Andrew Heine, Engineering Manager at Figma. Andrew shared his thoughts on setting learning goals, finding opportunities to take on management responsibilities, and the importance of getting enough sleep. Edited for length and clarity.

For Andrew’s advice for early-career engineers, visit the Codecademy blog.

Tell us about your current role and how you got there.

My current role is Engineering Manager at Figma on the prototyping team. Prototyping is a feature in Figma where, once you’ve made your designs in the Figma editor, you can and see animations, interact with them, view them in a more focused way, and do user testing. I’ve been here just about six months. I started as an IC.

When I interviewed, I interviewed for the manager spot, which was going to open up in a few months. I came in as an IC, which was a win-win sort of situation. I was working with the VP of engineering to find the right way to get me into a role that was a good fit, and I thought it was a good bonus to be able to be an IC for a couple months. It’s pretty good if you have the chance to come into a company and understand the code and see what it’s like to be an engineer at the company. As a manager, you will get some exposure to writing code, but you’ll have way less time to do it. So it worked out well.

I had been a manager prior to this, at a company called Atrium. I had also run a startup of my own for a few years before that. That was when I stopped just being an IC. I was doing everything that needed to get done at a three-person company. It wasn’t anything like what my job is today, but I did like the kind of variety that you get as a founder, and you get a lot of that as a manager too.

That was sort of how I got started thinking about being a manager. I was like, “Hey, I’m not really just writing code anymore. Do I want to go back to mainly being a programmer, or do I want to continue to interact with different functions?” Being a manager is kind of like being the founder of a team, and you might do a variety of different things depending on what the problem of the week is.

What interested you about management? Was it that feeling that every day is something different and you have a lot of different jobs and responsibilities?

That aspect of it, and then I think it would be flawed to pursue management if you don’t have a strong interest in people and relationships. It’s valuable for any career path to invest in relationships. As a manager, you do have to really care how people are feeling. I asked myself, what kinds of problems do I want to be thinking about in the shower? What kind of problems do I want to be getting better at, and reading books about? At that time I was more interested in reading a book about management than reading a book about design patterns. I felt I had grown a lot as an engineer, and I was curious about management.

That’s a great way to think about it, can you talk a little bit about your transition from IC to manager? What was that experience like for you the first time around?

It was great because if you’re at a growing company, it’s super easy to get support in this because often times your own manager might be interested in saying, “Hey, I want to manage managers.” Not to say this is always the case, but it’s pretty common that if you see a company that’s growing a person might be managing eight people on a team and they might be aware that the next step for them is to hire their kind of ninth person or 10th person. There’s a tipping point where you really can’t have a team that’s that big. They start thinking about how to grow their own career, and they think they’ll be able to kind of scale themselves up by relying on you.

That was the case for me at Atrium, where my manager was at their limit of reports. That’s pretty common at a growing company, where there are opportunities that come up where it’s not just a new team, but your own team having to split into two.

What was it like to manage people who used to be your peers?

It’s interesting and mixed. There’s a trust that you have when people know you’ve done similar work to them. That’s a big pro. There could be potential downsides I imagine, if somebody else wanted the position, but that wasn’t the case for me.

You have to kind of feel it out. Do I walk in the next day and suddenly have more respect because I have a title? Probably not. But at the same time people do want to have a leader, and I think people are pretty encouraging, pretty supportive. And it’s nice to have your peers know how to work with you already and trust you.

What do you see as a primary role of a manager on an engineering team?

If you were managing a football team, there’s two puzzle pieces. There’s what you know you have to get done — you know you’re going to have to kick some field goals. If you don’t have a field goal kicker, you need to either hire one or train someone to do that. You also can look at the assets that you already have, look at the skills your team has, and make a playbook that that team is going to be good with. You can change your team by hiring and by training, and you can change the strategies your team uses based on the personality types and the skillsets that you have available to you. It’s about the known requirements, and being resourceful with the people who you have.

Ultimately, you’re kind of accountable for everything, even though you’re not doing much of the work. You were the person who said, “We don’t need a field goal kicker.” You could blame the quarterback for missing a field goal, but really you’re accountable for that quarterback missing the field goal.

Is there a difference between being a manager and being a leader and if so, what do you see as the difference?

There is a difference between management and leadership, but oftentimes it’s the same person. The things that I think of as my deliverables are the management aspect: coming up with a roadmap, with priorities, with a hiring plan. Things that you have to do are often management. Then the stuff that’s not really a deliverable is the leadership: How you are around the team? Are you creating a culture where people feel comfortable? Where people feel motivated? Are you building a cohesive team?

I think of management as being the deliverables and leadership as the style.

Leadership is a lot easier when you’re doing the management part well, because you don’t have a bunch of fires going on. It’s hard to be inspiring when things are falling apart.

What are the biggest challenges that you’ve faced since stepping into a management role or a leadership role?

One is time management. As a manager, you will never do everything that you could do, because your role is pretty unbounded. It’s always a challenge to decide what not to do, whether you’re delegating it, whether you’re saying we’re going to live with this for a little while, or whether you’re going to take it on yourself as a project. It’s pretty easy to over-commit.

Time management, and risk management — deciding what stuff to look at and what stuff to trust is going to be fine without your involvement. It’s a tough thing. On a similar note, the trade-off between giving folks autonomy and doing what you think is right is also a tough thing as a manager. A lot of people think that as the manager, they get to call the shots, but it’s definitely not the case. You don’t want to be a dictator. It’s not good for ICs, and it’s not going to help them grow. Oftentimes they do know this stuff better than you. You have to develop a good intuition for when you’re going to step in and say something needs some additional scrutiny.

My default is to trust people who I’ve hired and who I’ve worked with. Their job is doing their work. But you also can’t let go 100%. That’s a tricky thing because you don’t want to be a micromanager, but you want to know enough about what’s going on to support people.

How do you help your team members grow, both as individuals and together as a team?

As individuals, there are a couple of ways to grow. One is by doing a thing that’s challenging. That’s probably the way that appeals to me the most — finding a project for people to be excited about, that is high leverage for the team. Once you’re able to do that, it’s really important to find a balance where the teammate is able to be pragmatic and be motivated by impact.

Also, they should have some freedom to be curious and learn the area around what they’re working on. It de-risks the project a little bit and it helps them solidify what they’re doing. It’s a balance between making sure that people aren’t being perfectionists, while giving them the space to fully understand what they’re working on and savor the learning.

Being very conscious about goal setting is also important. It can be pretty tricky as an engineer to set goals. A lot of times it’s like, yeah, I should just be a better coder, I should code faster. Those things are pretty hard to quantify, and it’s hard to know if you’re doing better at them, and hard to know how to do better at them.

It does help to just put in the effort to state a few learning goals: I want to understand this part of the code, I want to understand memory management and C++, something very specific. It seems nearsighted, but it is valuable to pick one thing and at the end of the quarter to look back and evaluate how a project did for that learning, even though you probably learned things beyond that one stated goal. It gives you a framework for reflecting on how you’re learning.

Growing as a team largely involves a feeling of shared ownership over priorities. Everyone has their role, but if you have a team where the priorities are understood and shared, then people have a lot more positive reward out of other people’s contributions and they feel supported in their own. That creates a lot of empathy and creates a lot of flexibility in how the team helps each other out. Having a sense of shared ownership, shared celebration, and shared responsibility is really great for a team.

What advice do you have for new managers or people looking to shift their career path and become managers?

The number one priority is to build good relationships with people. Make sure that that’s something that you enjoy, because your number one deliverable as a manager is trust. You can mentor our new hires, schedule 1 on 1s with other people on the team, make sure that you’re bonding with your peers and understanding what their needs are.

Additionally, there’s opportunity as an IC to take a little bit of extra ownership over a project. And getting good at working cross functionally is good. Understanding the hiring process is also ultimately going to be a requirement, but at the end of the day, none of these things are individually super important because you’ll learn them on the job.

The biggest piece of advice I have is to express interest to your manager about this, because the opportunities for you to have impact beyond writing code will vary per company. Your manager will probably be pretty excited to have you want to help out beyond writing code, and they can help you find an avenue for that.

Is there anything else that you think is important to say that we didn’t touch on already?

Drink lots of water. Stand up every half hour.

All good advice for sure.

Oh, and get regular sleep. Software engineering is such a mental thing, but taking care of your body is going to pay off pretty quickly when you don’t have wrist issues and you’re not burnt out. So drink water, get plenty of sleep. Stand up every half hour. That is important as having learning goals.

For more of Andrew’s advice for the next generation, visit the Codecademy blog.

Continuous Delivery is the ability to ship code quickly, safely, and consistently, and it’s a necessity for teams that wish to remain innovative and competitive. It’s focused on delivering value to the user and starting that feedback loop early — the ideal state of Continuous Delivery is one in which your code is always ready to be deployed.

Many engineering leaders think of CD as a workflow and focus on the tooling and processes necessary to keep code moving from commit to deploy.

But CD is more than just a process — it’s a culture. To effectively practice CD, you need to:

- Convey the importance of CD to your team

- Create a blameless culture, one in which developers feel safe dissecting and learning from mistakes

- Facilitate alignment between business goals and CD.

With the right culture in place, your team will be better positioned to get their code into production quickly and safely, over and over again.

Explain why CD is important

Processes fail when developers don’t understand their rationale. They may follow them in a nominal way, but they’ll have a hard time making judgment calls when they don’t know the underlying principles, and they may simply bend the processes to fit their preferred way of working.

Code Climate’s VP of Engineering, Ale Paredes, recommends starting with context over process. Explain why you want to implement CD, reminding your team members that new processes are designed to remove bottlenecks, facilitate collaboration, and help your team grow. As they get code into production faster, they’ll also get feedback faster, allowing them to keep improving their skills and their code.

Then, you can set concrete, data-based goals that will allow you to track the impact of new processes. Not only will your team members understand the theoretical value of CD, meeting these new goals will help prove that it works.

Connect with individual team members

Ale warns that when an individual developer isn’t bought into the idea of CD, they’ll “try to hack the system,” doing things the way they want to, while working to superficially meet your requirements. This may seem like it accomplishes the same goal, but it’s not sustainable — it’s always counterproductive for a team member to be working against your processes, whether those processes are designed to promote CD or not.

She recommends using 1-on-1s to get a sense of what motivates someone. Then, you’ll be able to demonstrate how CD can help support their goals. Let’s say a developer is most excited about solving technical challenges. You might want to highlight that practicing CD will allow them to take end-to-end ownership of a project: they can build something, deploy it, and see if it works when they’re shipping small units of work more frequently. If another team member is motivated by customer feedback, you can remind them that they’ll be getting their work into customers’ hands even more quickly with CD.

Creating a blameless culture

Once your team is bought into the idea of Continuous Delivery, you’ll need to take things a step further. To create the conditions in which CD can thrive, you’ll need to create a blameless culture.

In a blameless culture, broken processes are identified so that they can be improved, rather than to levy consequences. It’s essential that team members feel safe flagging broken processes without worrying that they’ll be penalized for doing so or that they’re singling out a peer for punishment.

A leader can help establish that blamelessness in the way they communicate with their team members. Ale’s rules for incident postmortems clearly state that there is no blame. Names aren’t used when discussing incidents or writing incident reports because the understanding is that anyone could have made the same mistake.

Convince the C-Suite

Fostering the right culture on your team is essential to effectively implementing Continuous Delivery, but it’s not enough. CD also requires support from the top. If your company is looking for big, splashy releases every quarter, Continuous Delivery will be a tough sell. Frequent, incremental changes are almost fundamentally at odds with the roadmap that the organization will set out for engineering, and how it will measure success.

To bring Continuous Delivery to an organization like this one, you’ll benefit from applying one of the core principles of CD: incremental change. You won’t be able to drive a seismic shift in one push. Instead, you might try Ale’s strategy and look for ways to introduce small changes so you can start proving the value of CD. For example, you might try automating deployments, which should cut back on incidences of human error and free up developer bandwidth for writing new code.

The Virtuous Circle

Process may start you on your way to Continuous Delivery, but you won’t get far. Pair those processes with a culture of CD, and you just might reach the Virtuous Circle of Software Delivery — the point at which each improvement yields benefits that motivate developers to keep improving.

For our series, 1:1 with Engineering Leaders, Code Climate and Codecademy for Business are speaking to managers and VPs about their career journey, leadership strategies, and advice for the next generation of engineers. Check out our previous interviews with Tara Ellis, Manager, UI Engineering at Netflix, Brooks Swinnerton, Senior Engineering Manager at GitHub, Gergely Nemeth, Group Engineering Manager at Intuit, Lena Reinhard, VP of Product Engineering at CircleCI, Andrew Heine, Engineering Manager at Figma, and Mathias Meyer, Engineering Leadership Coach.

Below is an excerpt from our conversation with Anchal Dube, Senior Engineering Manager at Zocdoc. Anchal shared her thoughts on the shift in mindset necessary to take on a manager role, the importance of having the right expectations, and the similarities between managers and tug boats. Edited for length and clarity.

For Anchal’s advice for early-career engineers, visit the Codecademy blog.

Tell us about your current role, and your career journey up to this point.

I’m a Senior Engineering Manager at a Zocdoc, and currently I’m overseeing a couple of different teams. One team is focused on the Zocdoc video service we launched in response to the pandemic and the fact that a lot of care suddenly needed to go virtual. It’s something that we built and launched over a two-month time period, whereas more typically this would have been a two-year roadmap. The other team focuses on our provider touchpoints and how we can use the relationship that we have with our providers to build a better connection with their patients.

In terms of my journey, I have a Bachelor’s in Computer Engineering and a Master’s Degree in Computer Science. I started out in the healthcare space, working at Epic, which is an EMR company based out of Madison, Wisconsin. I worked there as a Software Engineer and then as a Team Lead for a little under five years. That was my first foray into a leadership role.

Early on, there was a honeymoon period where I was really excited about what I really perceived as the next step of my journey, with a promotion and more responsibility. But about nine months into that, I really started questioning whether the role was for me, and whether I wanted to continue. Around the same time, for family reasons, I was looking to move to the East Coast. And so when I moved to Zocdoc, I actually came here as an IC.

I joined as a Senior Software Engineer and wanted to continue down the individual contributor path, but was impacted by an incredible manager and mentor I had at the time. He really took the time to understand my challenges and pain points from my previous leadership role. And he gave me a lot of motivation and advice on how to navigate that transition again, and to do it much more successfully the second time around.

So after being at Zocdoc for about two years or so, I went the management route again, starting with the team that I was already working on as an IC.

What was it that turned you off of managing the first time around, and how did that change, other than having a great mentor? Do you feel like it was circumstantial, or a mindset that you needed to change personally?

I think mindset was definitely a challenge. One thing that I recognize now, that I don’t think I did in my first stint as a leader, was that I really needed to take a step back from owning everything directly. My path to creating impact is not going to be by executing on a given project, but by empowering my team so that they can do so. And the skill set that I need to rely on is less computer science and computer engineering fundamentals, but more around how to create influence within a group of people.